The Christmas earthquake that shook Malaga in 1884: it opened up the land, changed towns forever and sparked new traditions

Estimates put the number of fatalities at between 800 and 1,200 people with around 1,500 seriously injured in the Andalucía region. The heavy snow that followed the magnitude 6.7 earthquake caused further suffering and deaths

Southern Spain knows what it's like to live with seismic risk ingrained in its very being. Still, some dates are just unforgettable. One of them is Christmas Day 1884 when, at 9.08pm on 25 December, just as family dinner was on the table and midnight mass was due, a violent earthquake shook the Axarquia area and the rest of inland Malaga.

The epicentre was located a few kilometres further up, in the mountain area of Arenas del Rey (Granada province), but the emotional and material impact was also deeply felt in Malaga. The tremor reached an intensity of X on the macroseismic scale, with a duration that sources put at between 10 and 20 seconds, enough to turn thousands of houses built with packed earth and poor masonry to rubble.

Estimates put the death toll at between 800 and 1,200 people, with 1,500 injured. The earthquake affected over 100 villages, towns and cities between Granada, Malaga and Almeria. The figures vary according to the different reports at the time, but all agree on one thing: it was the deadliest earthquake in modern history for the region of Andalucía.

Periana and Alcaucín

If there was one place in Malaga where the earth truly split open, it was Periana. According to historical sources, more than half of the houses were destroyed or left uninhabitable and a small hamlet within this village's borders, Guaro, literally disappeared from the map. Cracks cut through entire streets and livestock yards and corrals collapsed as though made of cardboard.

In Alcaucín, the ground opened up in the village square, splitting the village in two and damaging houses and the church. A brief, but eloquent, story has been preserved in local memory: when King Alfonso XII arrived weeks later to assess the damage for himself, a goatherd from the municipality, José Lucas, broke protocol, approached the monarch in tears and kissed his hand in gratitude for the help he had received, after telling him that he had lost his children, buried under the rubble. It was a humble gesture that symbolised a collective tragedy.

Zoom

Canillas de Aceituno

In Canillas de Aceituno, according to the Andalusian institute of geophysics, up to 15% of homes collapsed and 65% suffered serious damage. In Cómpeta, Frigiliana, Benamargosa and Algarrobo, the number of collapsed buildings was also significant. In Vélez-Málaga, the largest town in the worst-hit area, the earthquake damaged 1,291 homes and caused the bell tower of the church of Carmen to collapse. It was never rebuilt. The Axarquia area, so lacking in earthquake-resistant building codes and solid foundations, blindly bore the brunt of the tremors.

One human detail runs through all the accounts: open doors. Those who stayed indoors kept their main doors open, ready to run out at every aftershock. There were plenty of those too: over 100 aftershocks were recorded in the following weeks.

Many local residents slept in makeshift tents, huts, on threshing floors and in olive groves, despite the bitter cold. To make matters worse, a few days later, a record-breaking snowfall hit the area, increasing the death toll among the elderly and injured. During those days, people who had survived the earthquake then succumbed to hunger and exposure to the elements and died.

Poor communication delayed everything: it was not until 27 December that the full extent of the disaster was officially known. Then, on the 29th, when El Defensor de Granada newspaper appealed for help in the national press, in Madrid it was assumed to be an exaggerated report.

Zoom

The processions of fear

Panic spread along the entire eastern coast. In Nerja, according to the official chronicler José Adolfo Pascual, the tremors lasted 13 seconds, enough for the town to set up makeshift shelters and tents at Puerta del Mar and the Balcón de Europa, where a temporary telegraph line was also installed. There, they carried the statues of St Michael the Archangel and Our Lady of Sorrows in procession to pray for protection.

In Vélez-Málaga, there is a municipal record, made by the secretary and dated 21 December the following year, that documented the following: "A major earthquake occurred on 25 December at 9pm. The tremors continued for months, some persisting until July". The town lived on edge for six months.

The visit of King Alfonso XII

January 1885 provided a symbolic image for the history books: Alfonso XII visiting the most devastated areas, handing out money to the injured and launching a national fundraising campaign. A benefit concert was organised at the Teatro Real, with the participation of the Fernán Núñez duchy and the attendance of the royal family, which significantly boosted the fundraising effort.

The king's Andalusian tour produced anecdotes, moments of solace and also a popular myth. In Nerja, his visit on 20 January 1885 brought public aid and the title of "Excelentísimo" awarded to the town hall. Reality surpasses legend: the Balcón de Europa had already been named as such, although collective memory attributed it to the king during this visit.

The aid multiplied. Forty countries sent donations, totalling more than three million pesetas at the time. The Comisión Regia (royal commission) managed compensation payments for more than two years, financing new homes, schools and churches. In the Axarquia, entire neighbourhoods were rebuilt - such as the Carmen district in Vélez - and new settlements sprung up in Periana. With these came the first ideas for more resilient construction.

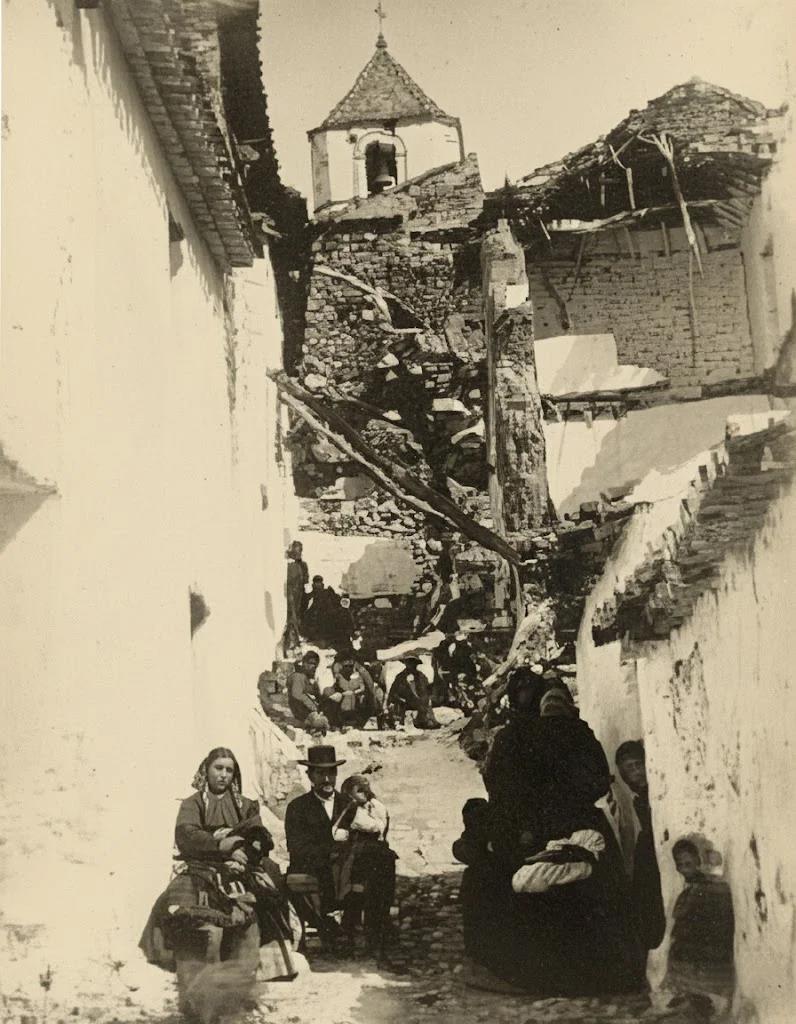

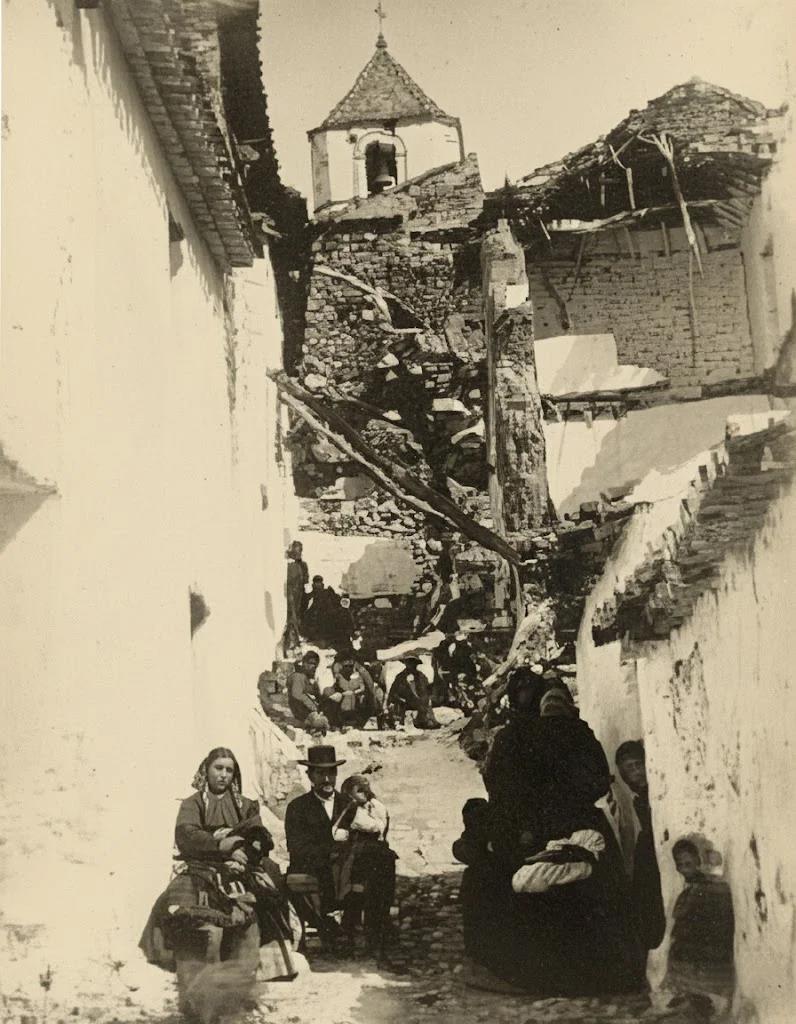

That humanitarian wave coincided with another milestone: the birth of photojournalism, with images showing for the first time across all Spain the villages and towns reduced to rubble. The catastrophe ushered in a different way of looking at disaster.

The raffle in Canillas de Albaida

The earthquake did not hit Canillas de Albaida with the same ferocity as elsewhere, but it left a deep emotional scar. Houses cracked, fear took hold and, in the early hours of the morning, the locals carried their patron saint, the Virgin of the Rosary, out in procession through the streets in an attempt to put a stop to the disaster. This popular initiative was credited with blocking the strongest aftershocks.

Since then, the village has maintained a ritual identity marked by that December: votive prayers, collective memory and a community practice that has its roots in the seismic trauma: the traditional auction or raffle. This type of funding mechanism came about in times when there was no insurance or immediate public aid and a raffle (or 'rifa') would be held to raise funds for the church and for the residents themselves. What began as a means of survival is now also a cultural landmark event.

So many decades have passed since that frightening Christmas -141 years as of this year - and the Axarquia area still carries the date buried in its DNA. Periana, Alcaucín, Vélez, Nerja and Canillas de Albaida preserve some rituals and now have new streets, neighbourhoods and urban scars that were born from that historical, ground-shaking event.