The night the dictatorship put an end to gay life in Torremolinos

A huge police raid in 1971 left hundreds arrested, many business closures, and a protests from the press and the embassies: “They arrived with machine guns”

ALBERTO GÓMEZ

Viernes, 11 de mayo 2018, 10:12

While Spain languished under the Franco dictatorship's moral constraints, Torremolinos was opening the door to freedom, excess and diversity.

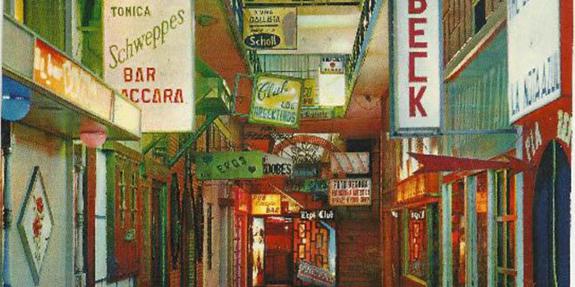

It was the sixties. In Plaza de La Nogalera and Pasaje Begoña the nights were for living and the days were for sleeping. There opened the first gay bar in the country, Toni's Bar (in 1962) and the first lesbian club, Porquoi Pas? (in 1968). More local establishments like Fauno, Incógnito and Düsseldorf soon opened alongside, completing the alley, which was totally unique for its era.

Although the predominant theme was LGBT, there were also restaurants frequented by families, flamenco venues, adult clubs and small jazz bars. The latest music was regularly played and modern drugs circulated freely. Dodging censorship, books arrived intact from London or Paris. A counter-cultural movement had taken seed, an open bar of excitement, alcohol, sex and art - the kind of lifestyle that was enjoyed by John Lennon and Sara Montiel. The money earned from tourism meant that authorities had been looking the other way for years.

Torremolinos became a mini New York, an uncontrolled, happy exception to the oppressive regime. Until 1971. On 24 June of that year a huge police raid took place, changing everything.

At 11pm, the police forced entry into all the establishments of the area, either closing them down or, at best, heavily fining them. They alleged offences against public morality and commonly accepted behaviour. Information from the era suggests that 139 people were arrested. Other reports raise the number to over 400, the majority being tourists.

Memories

The raids were triggered by complaints from the more conservative sectors of the province. Testimonies from the night are sparse, but Ramón Cadenas, a 73-year-old retired businessman, remembers it as if it were yesterday.

Pasaje will be declared place of historic remembrance

-

The Andalusian Parliament has unanimously approved a decision to officially recognise the value of the former Pasaje Begoña.

-

The alley, now named Pasaje Gil Vicente, has made its first step towards becoming a 'Lugar de Memoria Histórica y Democrática de Andalucía', a title that will pay tribute to its significant position within the political history of Spain.

-

The motion was debated in the Seville parliament on 3 May and approved by every political group.

-

Promoted by the recently formed Pasaje Begoña Association, this process hopes to recover the area's previous image.

It was horrific. The police blocked all exits of the Pasaje Begoña. They brought machine-guns. At first they came with four or five vans, but afterwards buses arrived too, to take all those who had been arrested, he said.

The most fortunate were freed from the police cells in the early hours with a fine of 3,000 pesetas. Tourists were deported back to their countries. It caused a scandal that angered the international press. The raid was covered by Der Spiegel, the most important weekly magazine in Germany. The Sunday Times reported on the story with the following headline Tourists held in nightclub raids in Spain.

On 25 June, SUR published The closure of Torremolinos establishments, including the Caramela club and bars Evans and Noe, has been ordered by the civil governor of the province (Víctor Arroyo). The decision of the government is triggered by repeated infractions to the laws in force concerning public morality and commonly accepted customs.

Other local establishments such as Pipper's were fined 10,000 pesetas. Various foreign embassies protested against the Spanish government for the arrest of tourists, but the raids took place again over the following days.

Cadenas had opened a bar called Gogó, barely one month previously. The business lasted 29 days. They didn't arrest me during the first raid because I silenced all the customers and closed the door and the windows. When the police called we didn't answer, but afterwards, they arrested me many times. I called it the revolutionary tax, because you paid 3,000 pesetas and they let you free one or two days later, but this was unsustainable and I had to close.

Those raids were a blow to the fabric of the Torremolinos economy, which never recovered its splendour of the sixties. They were also an attack on freedom and sexual diversity.

It was the beginning of the end. The more modern and liberal people left for places like Ibiza, explains Torremolinos Chic, a website created by José Luis Cabrera and Lutz Petry: It's paradoxical that during the sixties there was more freedom then at the start of the seventies, when the censorship began to get worse.

The president of the Pasaje Begoña Association, Jorge Pérez, remembers that the area deteriorated after the raids. The festive atmosphere gave way to a row of empty establishments. The alley was all but deserted.

The restoration of democracy in Spain allowed Torremolinos to recover its position at the core of leisure and LGBT tourism, helped by the popularity of La Nogalera area. Today the former fishing village, free from the Franco dictatorship, has once again become the Andalusian capital of sexual diversity, years after the raids that changed everything.