The bearded vulture: an 'archaeologist' among Spain's birds of prey

Human artefacts including a 13th century sandal, a crossbow arrow and an 18th century basket fragment have been found in their nests

J.M.L.

Toledo

Friday, 19 September 2025, 16:25

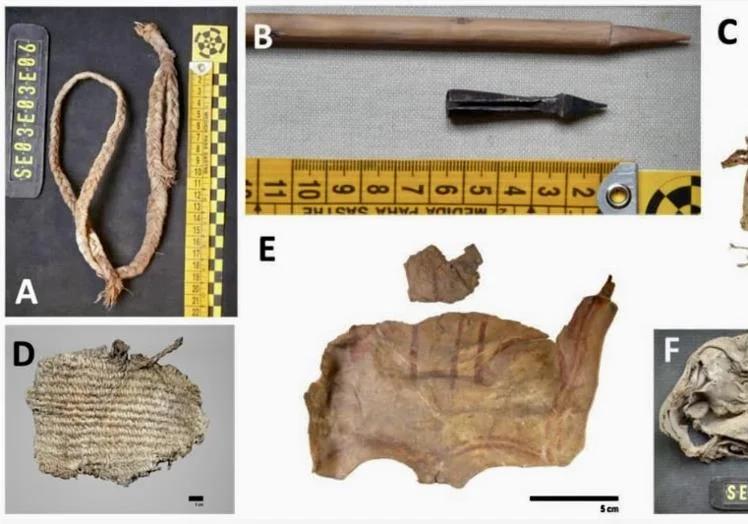

The bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus) is one of Europe's most endangered birds and its survival depends on high quality habitats to facilitate breeding. These must be in steep places, away from roads and with low human density. Their nesting sites have also shown that they are true archaeologists, albeit of the feathered variety, as objects such as a fragment of basketwork from the late 18th century, a complete esparto grass sandal from the late 13th century, a crossbow arrow and a fragment of sheepskin painted with ochre from the 14th century have been discovered in their nests.

The use of carbon-14, a radioactive isotope of carbon that forms in the upper atmosphere and is ultimately absorbed by living beings through respiration and feeding, was fundamental to dating these artefacts. A group of researchers from the Catalonia Institute for Energy Research (IREC) led the study, in participation with the University of Castilla-La Mancha and support from CSIC - Spain's chief research funding council - together with scientists from the universities of Cantabria and Granada. They analysed the materials used to build these nests in search of more information on the feeding habits of this species from the Middle Ages onwards and the historical, ethnographic and biocultural conditions of the areas they populated.

Remains of human origin

Over the years, the team has examined more than 50 well-preserved nests in the southern half of Spain, where the species became extinct some 100 years ago. Some 50% of the European population of bearded vultures now lives in the Pyrenees. The findings have been astonishing, with a total of 2,483 remains recovered for analysis. The majority (2,117) were skeletal remains due to the vulture's carrion diet, along with eggshell fragments, which would indicate that breeding and nesting took place. Still, more surprisingly, 9.1% of the remains found were of human origin: 226 anthropogenic (human influence on nature) objects, including 25 artefacts made of esparto grass, 72 of leather, 11 of hair and 129 cloth fragments.

Zoom

Among the handcrafted objects that bearded vultures acquired and then used to build their nests in caves or protected rocky outcrops, part of an esparto grass sling rather stands out. The anthropogenic elements found are of great ethnographic value as they are similar to those found in nearby Neolithic caves, demonstrating the use of plant fibres in the Iberian Mediterranean from as far back as the Epipalaeolithic period, some 12,000 years ago.

Furthermore, eggshell remains are useful for comparative toxicological studies, which is essential for understanding pesticide loads and the history of localised extinction of the bearded vulture in some areas. This information could be key to the recovery of the species in Europe.

This scientific study, published in the peer-reviewed, scientific journal Ecology, has revealed that the bearded vulture reuses all kinds of materials over the long term, documenting the age of nests, which are authentic "natural museums" that connect them to the lives of our human ancestors and are an open book on the evolution of ecosystems over the centuries.