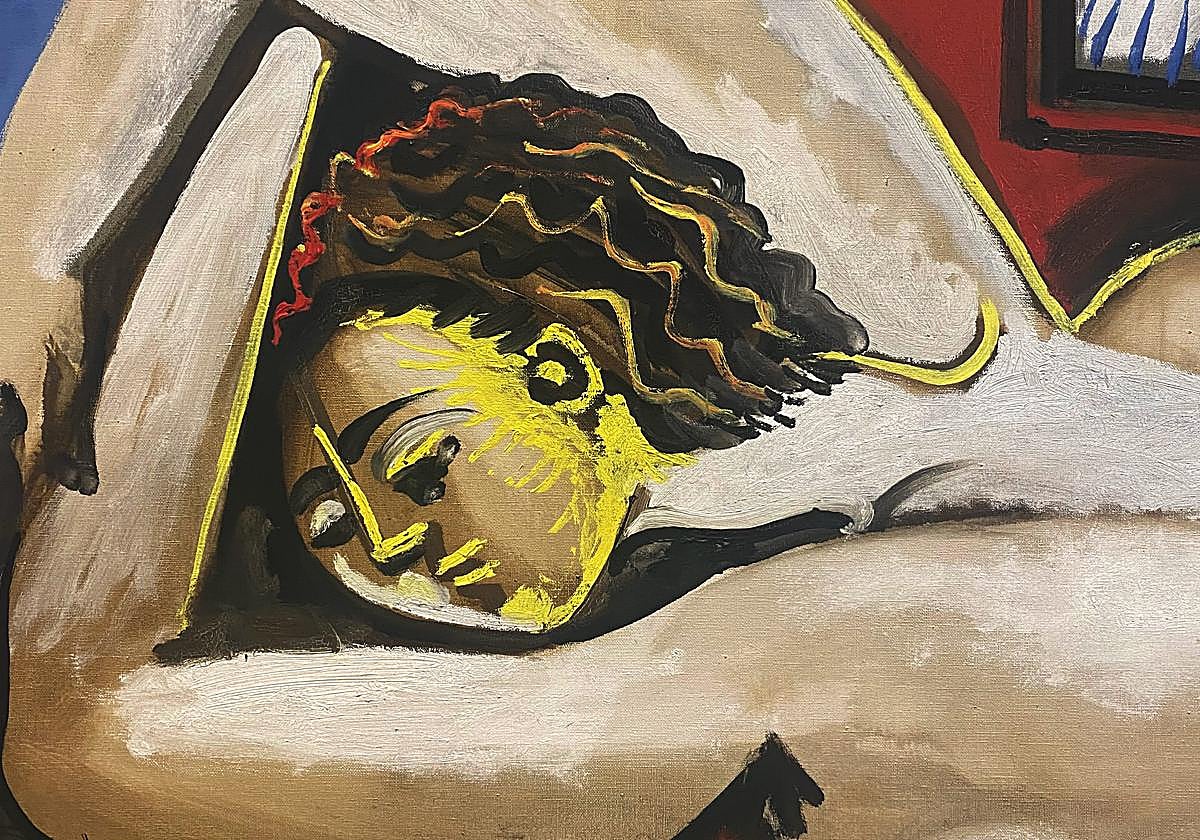

How much does it cost to protect a Picasso?

Malaga's six main museums invest over three million euros a year to protect their collections. Their greatest concern? Vandalism by activists

Just leaning in a little too close to a painting to see its details will most likely lead to getting scolded by museum security. A warning for trespassing across a carefully guarded, invisible border. Although most of the time it goes by unnoticed, the security department is one of the most critical in the museum world. It always has to be aware of potential robberies, altercations, terrorist attacks and fires.

However, the most worrying threat for security services are attacks by climate change activists on artwork - a phenomenon that has gained traction worldwide in the last couple of years. The museums in Malaga are all too aware of this, and have stepped up their security protocols to prevent such occurrences. So, how much does it cost to protect a Picasso, a Sorolla or a Barceló? And how can these threats be prevented?

El coste anual en seguridad por museo en 2024

Museo Ruso

Museo Picasso

616.527 €

1.014.548 €

Centro

M. Carmen Thyssen

Pompidou

414.368 €

612.830 €

Casa Natal

Museo de

de Picasso

Málaga

277.368 €

281.869 €

En total, 3.217.510 € al año

El coste anual en seguridad por museo en 2024

Museo Picasso

Museo Ruso

616.527 €

1.014.548 €

M. Carmen Thyssen

Centro

414.368 €

Pompidou

612.830 €

Casa Natal

Museo de

Málaga

de Picasso

277.368 €

281.869 €

En total, 3.217.510 € al año

El coste anual en seguridad por museo en 2024

Museo Picasso

Museo Ruso

616.527 €

1.014.548 €

M. Carmen Thyssen

Centro

414.368 €

Pompidou

612.830 €

Casa Natal

Museo de

Málaga

de Picasso

277.368 €

281.869 €

En total, 3.217.510 € al año

El coste anual en seguridad por museo en 2024

Museo Ruso

Museo Picasso

616.527 €

1.014.548 €

Centro

M. Carmen Thyssen

Pompidou

414.368 €

612.830 €

Casa Natal

Museo de

de Picasso

Málaga

277.368 €

281.869 €

En total, 3.217.510 € al año

The answer lies with the museums of Malaga, which do not skimp on guaranteeing the protection of their collections. In fact, the surveillance and protection expenditure at the city's major museums amounts to just over 3.2 million euros a year. This includes a total of over 70 agents and guards. Unsurprisingly, it is the museum with the most visitors, and the most highly valued collection, which invests the most in security. And that, of course, is the Museo Picasso.

The value of the 385 pieces housed in the Museo Picasso on Calle San Agustín is immense - just one of the Malaga-born artist's works sold for 179 million dollars at auction. The foundation therefore spends over a million euros every year on security. This means that roughly one out of every three euros spent on museum security in Malaga goes towards protecting Picasso's works. And while the Museo Picasso, which is the most visited in Andalucía, with 779,279 yearly visitors, prefers not to disclose these figures for 'security' reasons, the fact is that this data is public and readily available on their very own website.

The next biggest spenders are the Museo Ruso in Tabacalera and the Centre Pompidou in Muelle Uno, which invest 616,527 and 612,830 euros respectively into the protection of their collections each year. This is followed by the 414,368 euros allocated by the Museo Carmen Thyssen to preserve its collection of 19th- and 20th-century Spanish paintings in the Palacio de Villalón.

Zoom

As for the Museo de Málaga, its latest surveillance and security contract amounts to 281,869 euros, while the Casa Natal closes the list at 277,368 euros. The city's six main museums therefore have a monthly security expenditure which exceeds a quarter of a million euros. This is not including the CAC Málaga, which has refused to provide its data.

The all-seeing eye

Beyond the money, what is most important is how paintings and sculptures are protected in practice. And the most crucial elements of any security service are "the people behind it". José María Requena, the head of security at the Museo Carmen Thyssen, has a staff base of 13 agents, provided by security company Menkeeper, who monitor everything from the main entrance to the control centre, guarding the Palacio de Villalón's most secret rooms. These have been exclusively opened for the first time for this SUR report.

A double-lock door system - the same used in banks - already signals that we are entering a restricted space. We are greeted with a bright red alarm light, just like in the movies. The control room is operated 24 hours a day. From here, every last corner of the art gallery can be watched: 128 cameras show the rooms and artwork, but also corridors, lifts, storerooms, courtyards and doors. Nothing escapes these all-seeing eyes - nor those of the watchman who controls the monitors.

.jpg)

Zoom

.jpg)

Technology is also fundamental to defence and protection. Unlike the static surveillance cameras that are used in the street, the museum has 360-degree Domo cameras. The lenses are covered to prevent people from knowing where they are pointing. This "not only has a dissuasive effect, but also helps visitors not to feel as though they are being watched". While the operator brings up the image he wants to enlarge from the hundred-odd camera displays on the monitors, Requena explains how security is coordinated from this very control centre. This is where all the data comes together, including the information from the building's sensors, which can detect anything from temperature changes to vibrations, and warn of potential break-ins.

However, museum heists like those from the movies are not the museum security department's main concern. "In real life, it is virtually impossible to steal a painting because, in addition to surveillance, smaller works have security hooks that prevent them from being taken down. What worries us most at the moment is the vandalism of art to attract attention," says the head of security at the Carmen Thyssen. He continues our tour through the depths of the museum until we reach the rooms where, alongside works by Darío de Regoyos, Romero de Torres and Zuloaga, those discreet Domo cameras that watch us, even if we don't know it, are hung in every corner.

Zoom

"We are not an airport"

The museum has maximum security, but it still has its limits. The scanner at the entrance checks the inside of all bags entering the museum, and the works on display are permanently under surveillance. "But we are not an airport and we don't frisk visitors," explains José María Requena when asked about cases of activists pouring paint over jewellery or glueing their hands to frames. "Their intention is not usually to damage the work but to attract attention, but the speed and nerve of their actions greatly increases the risk that they will eventually end up causing damage," says Requena, knocking on wood.

He also makes clear that the museum's surveillance systems should not interfere too much with the visitor experience. "Our job is to protect the collection, but also our visitors, who must have a sense of security without feeling their privacy is invaded, which is the most complicated thing." Requena has been in charge of security at the Palacio de Villalón since its opening in 2011, during which time more than two million visitors have passed through its rooms - and its security cameras.

Zoom

Weapons are also used to protect the museum, although only the guard at the main entrance holds one. This is intended to act as a "deterrent", like the cameras in every corner. These more traditional security precautions are joined today by newer technology, such as face detection systems. However, the latest security advances in Artificial Intelligence are far from matching human intelligence. "No matter how many cameras and tracking systems you have, technology will never be able to outperform human analysis of the situation or the guards' expertise," says Requena, just as his colleagues call him over via walkie-talkie. It is as if they had been listening in and wanted to make it clear that the human element of security really is the most important.