Computers versus books: the dilemma of the schools of the future

Sweden's proposal to reduce the use of devices in the classroom has opened the debate on what impact technology has on education

Raquel C. Pico

Madrid

Friday, 8 September 2023, 13:32

If we play the futuristic game of imagining what the world of tomorrow will be like, we think of a society given over to technology. Screens will be everywhere and tech tools will be used for everything. This is a logical projection, since these solutions already play a major role in our daily lives. Schools are not on the fringes of society and its changes and, for this reason, we also imagine the school of tomorrow to be full of technological devices.

After all, technology has already reached the classroom and students are already learning with apps, tablets and computers. Some 78 per cent of Spanish teachers - in both primary and secondary schools - believe that the digitisation of classrooms will grow in the next three years, as revealed in a recent study by Epson. However, for 64 per cent, getting to that point will be a challenge. While 60 per cent of respondents believe it is important to increase the use of technology to achieve hybrid learning, 51 per cent acknowledge that they are not "technologically trained" to deal with the digital transformation at school.

At the same time, some movements have begun to question the role of technology in schools. In Silicon Valley, the epicentre of technological development, new schools aimed at the children of elite workers have started listing the absence of technology in the classroom among their selling points.

The recent case in Sweden - where experts are considering the link between poor reading comprehension test results and technology use - has spurred debate in Europe: are screens holding back learning skills?

Simply blaming screens seems, however, too simple. Edutech, the cluster that brings together companies and organisations in the ICT and education sectors, stresses that Sweden has not abandoned digitalisation, but has asked a group of experts to analyse what changes should be made in the process. And, as Sylvie Pérez, psychopedagogue and lecturer at the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences at the Open University of Catalonia (UOC) said that, "it is not that they are withdrawing all technology", but rather that they have put the development of new ideas on hold.

Is it a question of technology or is it something more complex? After all, figures do show that reading comprehension has fallen (and not only in Sweden). Pérez stated that reading ability is assessed through written expression (which opens another point of analysis, because reading and writing are not exactly the same thing), but she also frames the data in a broader context, in which children show a slower development, marked, perhaps, by a more protective environment.

"Both the analysis of the causes of the decline in reading comprehension and the impact of technology in the classroom are very complex questions that deserve calm and thoughtful answers," said Josep Lluís Segú, member of the board of directors of Edutech Cluster.

The role of technology

In some ways, the initial problem may not be so much in the technology as in what is done with it. "Using technology in the classroom does not mean that children spend five hours a day at school in front of their computer or tablet," said Segú. "The debate should be about what technology to use, how to use it and what for. We should focus the debate on what is the best way to use technology in schools," he added.

The digitalised school - which is not exactly a school without books, but one in which there are more tools to complement them - implies a transformation that goes beyond adding gadgets. It means rethinking how things are done and how information is transmitted to schoolchildren. "If you incorporate digital blackboards to do what you can do with a book, you don't need them," said Pérez. In other words, technology is not just a medium, but functions as a tool that opens up new educational possibilities. "What better way to understand what is going on inside a volcano than by entering an erupting volcano? Seeing and hearing what's going on inside," Segú added.

"Smart use of technology by teachers and students improves educational results"

Josep Lluis Segú

Member of the board of directors of Edutech Cluster

"Technology also helps teachers to improve their classes," added Sylvie Pérez, with resources, information and the possibility of sharing all these elements with others. Edutech also points in this direction. "An intelligent use of technology by teachers and students improves educational results," explained Josep Lluís Segú.

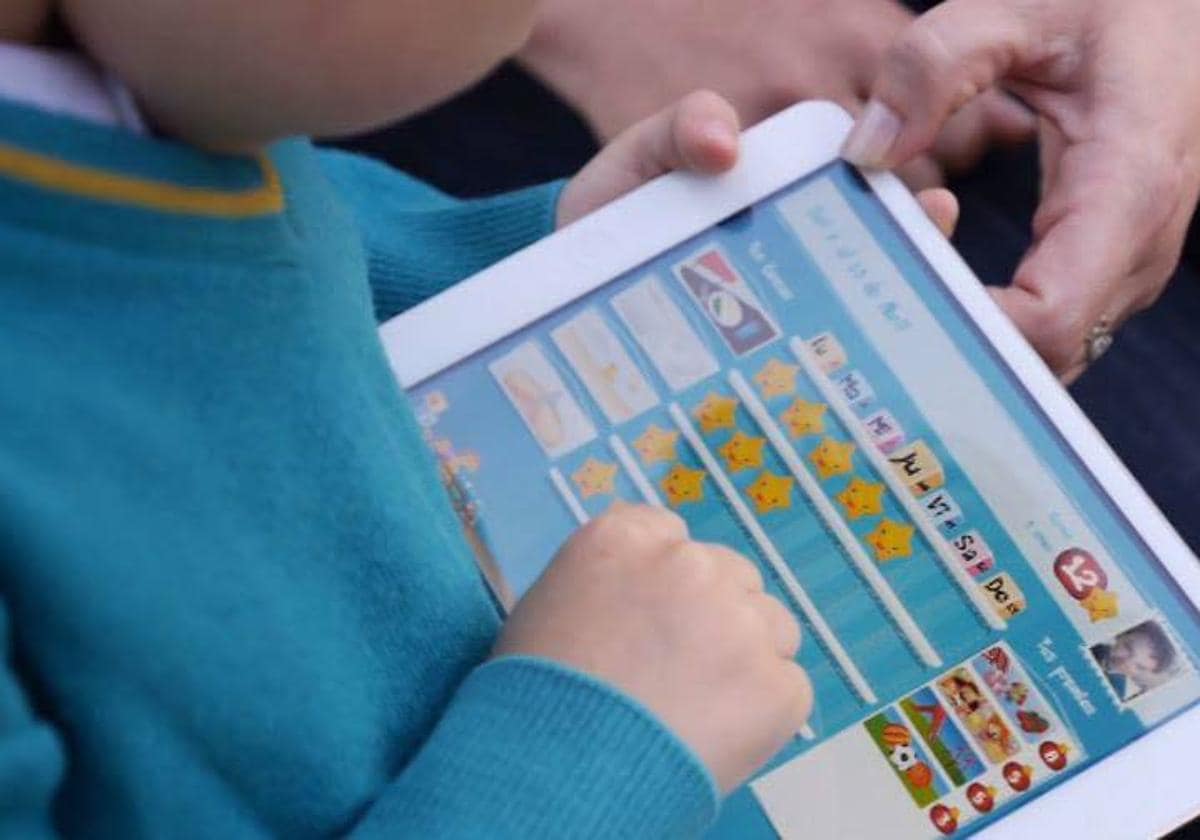

Even good technological practices have an impact in other areas. "Technology is allowing for a democratisation of learning," said Pérez. For one thing, it makes it easier for almost all children who have difficulty learning, for one reason or another. Thanks to technology, it is possible to do something as simple but fundamental as playing with the size of the fonts and better reach schoolchildren with visual difficulties. Tablet apps simplify communication with children with autism spectrum disorders.

And, above all, these tools are essential for personalising attention given to students, so that teachers can adapt to their learning needs of their and ensure that no one is left behind. "Some people will understand it by reading it, some students will need diagrams and others will need you to show it to them on video," explained Pérez. "The more tools you have, the better you can reach students," she added. This is not à la carte education, but one in which everyone can find a way to get to what they need to learn.

"Technology allows each student to progress in a skill according to his or her ability and pace of learning," Segú explained. "It allows the autonomous work of each student to be adapted according to the previous answers or the help requested to solve each challenge," he added.

"Technology is enabling the democratisation of learning"

Sylvie Pérez

Open University of Catalonia (UOC)

But, of course, technology does not need to be everywhere and at all times. That is one of the starting problems, as Pérez said, in what is required of teachers. When technology is incorporated as a sort of total concept - this idea of digitising all classrooms - it adds pressure to the daily work in schools and misses that key point that technology will bring something more. As the expert explained, one can use a digital game to enrich the history lesson and then go back to the same old methods in Spanish. "Technology is not an end in itself. It should always be at the service of the teaching-learning process. It should help in the teaching task without interfering", Segú said.

The world of the 21st century

Finally, the debate cannot ignore another fundamental issue, which is that today's world is dominated by these tools. "Technology is the new literacy," Segú added. "It is totally present in our lives, so students must learn to use technology correctly during their formal education," he said. Closing off the use of technology in schools means eliminating something as common as "playing an educational video", as Pérez stated. "We attack the modalities, but that's not the problem," she said. "It's not the mobile phone that is harmful, but how I use it might be," she added.

In fact, for education experts, the debate is about more than the presence and use of technology, it is about the ramifications of who uses what, how and where. Segú said that one of the risks they are most concerned about with the uses of technology - along with inappropriate use - is inequality. "Technology should not increase inequality between students and schools, it should compensate for it, minimise it," he said.