A perfect storm: these were the reasons behind the historic dramatic decline of wines produced from Malaga's vineyards

Until the 19th century the traditional wines of the province enjoyed great fame in Spain and abroad

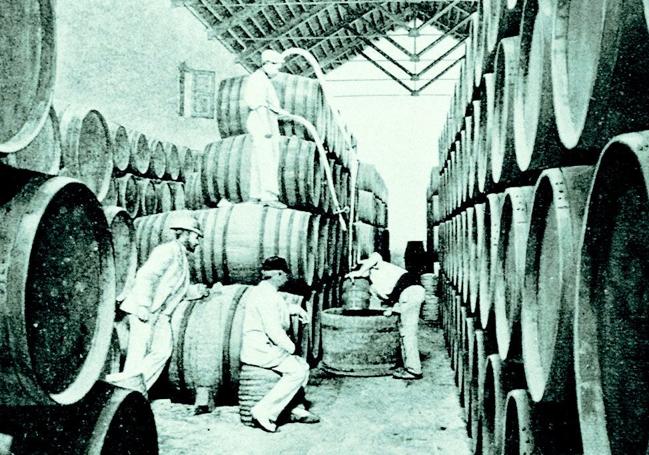

It was a real luxury product, often appearing as one of the most expensive alcoholic beverages in prestigious Parisian restaurants. From Los Montes - the hills surroundng Malaga city - hills to the capital of France. Until the 19th century the traditional wines of Malaga enjoyed great fame in Spain and abroad.

History books point to the arrival of phylloxera as the most critical moment for vineyards in the province and in a large part of the country. This pest was first found on the Iberian Peninsula on an estate in Moclinejo in 1874. It appears to be practically the sole culprit in a crisis that hit many small viticulturists in Malaga particularly hard.

However, a doctoral thesis by Malaga engineer Francisco Pérez Hidalgo now sheds a little more light on this turning point in Malaga's wine history. Entitled 'The end-of-the-century crisis for Malaga wine. Change in the production model and the decline in trade (1878-1933)', the thesis written by this researcher and winemaker has managed to analyse and portray what he defines as "a perfect storm" for the decline of Malaga wine.

This perfect storm was born of several causes, but one, not phyloxxera, was "due to the disappearance of the traditional vineyards of Los Montes de Málaga", as detailed in this doctoral thesis, presented on 16 September and graded as Outstanding, (better known as Summa Cum Laude - 'with the highest praise'). In particular, the thesis points to the disappearance of Pedro Ximén, which until then had been the predominant grape variety alongside Malaga's version of the muscat grape.

Although the trigger was phylloxera, Pérez Hidalgo also points to a bad technical decision, as phylloxera had also hit France years earlier, but there the replanting of the vineyards was successful and the plague only marked a break in production. However, in the case of Malaga, it was decided to pull up the affected vines and replant them with American riparia rootstock. "It was the first to be used when the government provided it to farmers through the nurseries that were established in Malaga," explains Pérez Hidalgo. The choice was not successful in the Montes area - it did not take root.

However, there is another, more important element to consider in that crisis. According to this doctoral thesis, the low profitability of grapes and the loss of international markets meant that "small farmers and the Malaga bourgeoisie were unable to replant the vineyards again." This crisis in turn led to an exodus of many wine-growing families and the desolation of the Montes de Málaga, now a natural park.

Curiously, the American seedling chosen did perform well in the coastal area, but it was mainly dedicated to the production of sultanas of the muscat grape variety, which experienced a high point in terms of prestige, commercial success and a decent price for the growers. However, when the California sultana came into play on the export markets, it was no longer profitable to continue replanting this variety.

The poor choice of a seedling and the competition from sultanas are just two more causes to be added to this perfect storm. Many Malaga winemakers who were mainly dedicated to export began to change their production model too. Thanks to the arrival of the railway to the city, they began to bring in wine from other areas of wine production such as Montilla or La Mancha. "This led to a change in the product", explains the author of this thesis who, in addition to being an engineer and historian, is co-owner of Bodegas Pérez Hidalgo in Álora.

By bringing in wines from other parts of the country, the natural sweetness of the wines that were made in Malaga gradually disappeared. Thus, they began to produce natural sweet wines with extra alcohol added. The alcohol used was mainly industrial standard, obtained from potatoes or beetroot, and mainly from Germany.

Another economic element that added fuel to the fire of this crisis was the increase in government taxes on alcohol and the lack of international agreements with France and Germany, which were very common destinations for Malaga wine exports. Despite its prestige, it became an expensive product. It ceased to be competitive with other wines such as fortified wines from Oporto, Madeira or even Jerez.

Moreover, as Francisco Pérez Hidalgo describes in his thesis, there was a change in tastes towards fresher, more aromatic wines, especially those with lower alcohol content. Here the researcher is quite categorical: "Malaga did not know how to adapt to the new tastes, nor did it know how to open new international markets, among other reasons because its competitors had been well established in the English market since the end of the 18th century."

With all these elements, a more concrete explanation is proffered as to the great crisis of Malaga wines. The trigger may have been phylloxera, but poor technical decisions and higher taxes were the main causes of what was the main agro-economic sector in the province of Malaga in the 18th and 19th centuries.