Ver 123 fotos

Drought in the Sierra de las Nieves: What will happen to the pinsapo firs?

The appearance of numerous dead or dying trees is causing concern among visitors. SUR goes to the national park with the leading experts on this unique species to analyse the situation on the ground

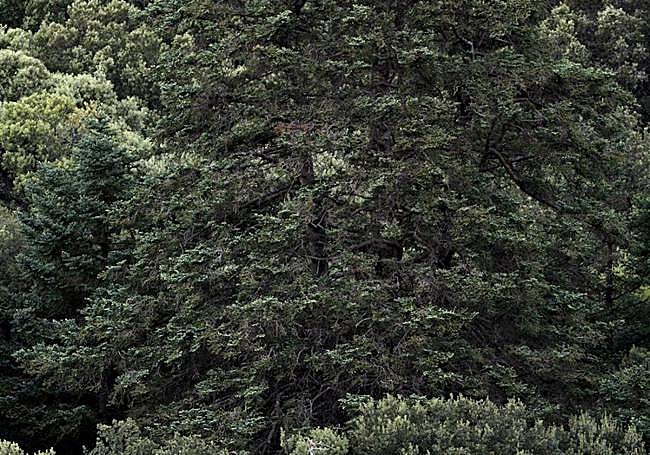

Visitors to the Sierra de las Nieves national park have raised the alarm: more and more trees are being found dead or with dried out tops and branches. Hardly any rain has fallen since December and this prolonged drought, together with the hot weather, is affecting part of Malaga's population of the Spanish fir known as the pinsapo.

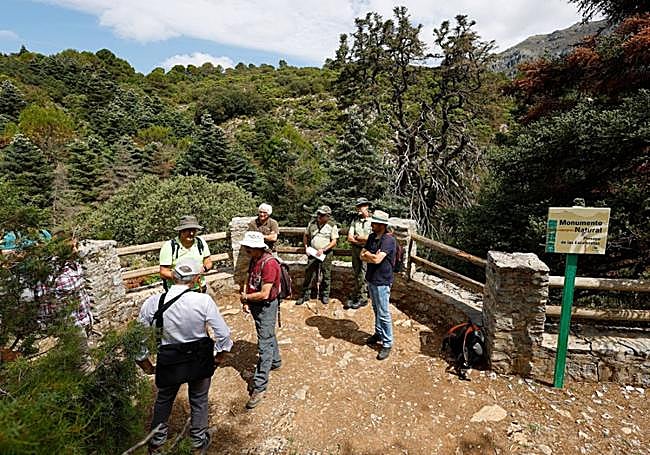

In the light of these concerns SUR brought together leading specialists in this unique species, an icon among the province's vegetation, to analyse it on the ground. Their tour of the park began in Parauta, in the heart of the Serranía de Ronda, in a pinsapo wood popular with visitors, and also a place where the sharpest decline in their condition can be observed.

-k11B--748x524@Diario%20Sur.jpg)

The situation

It's true, many trees are dry and dying

What visitors have observed is true: the lack of water respects no age, with as many young trees dying as old. "Natural selection is very much at work here: those that are weaker or in a worse condition are being affected," said Rafael Haro, director of the Sierra de las Nieves National Park.

But, like good detectives, you have to look at the crime scene as a whole, not just at the detail of the corpse, but also at other details such as the ground where the tree is rooted, often a rocky area with hardly any fertile soil available. The trees on the less humid and poorer-oriented slopes are also more prone to decay, while those facing north have better prospects.

When the tree loses vitality due to water stress, it is easier for insect borers and fungus pests to attack and kill them. "Sometimes part of the tree breaks off, but if it regains vitality, it can branch out at other points," to form what is known as a candelabra fir (because of the shape of its branches). "Only the treetop dies, but the rest survives and gives out secondary branches," added Haro.

Competition for water and nutrients is also great, as, paradoxically, the density of trees per hectare is still very high. "The one that is best positioned, or has the greatest genetic potential, is the one that survives," he said.

This "bad image" for visitors is heightened by the fact that this is one of the busiest walking routes, while people do not usually access higher and steeper points. In addition, dry trunks are left in place, unless they affect a footpath, so the carcasses remain visible for a long time.

"We let the forest function on its own and trying to eliminate them all would have a prohibitive cost. What dies and falls to the ground is eventually reintegrated into the soil. In fact, even when some of them are cut down, they are usually left to be metabolised by the organisms that decompose them," said the expert.

Las Escaletas

A centuries-old tree in its last days

The deterioration of the pinsapo known as Las Escaleretas, which has been declared a natural monument and has its own viewpoint on the path, is one of the main reasons why hikers raise the alarm. "It's because it's very old," said the park's director. The estimated age is about 450 years, although no tests have been carried out to find out exactly how old it is so as not to damage it further.

"People are very alarmed to see it like this, but it is in a state of senility, and just as happens to other large specimens, there comes a time when they can't hold out any more and we lose them," said Haro. But the expert insisted that, in this case, the explanation lies in its old age, above and beyond other circumstances.

Until now it has been the largest known pinsapo, both in diameter and height, but many of its main branches have already been lost.

Interestingly, this year it has produced fir cones, potential offspring. "Maybe this is the last time," said Haro. The path that leads to the viewpoint is the point where most trees are dying.

Analysis

The pinsapo is resilient to change

At this point, José López Quintanilla, coordinator of the Junta de Andalucía's pinsapo recovery plan, explained. "There is mortality, although sometimes you see more than there really is, because the eye is drawn to what is most striking," he said. This includes the red treetops of those affected by Cryphalus numidicus, bark beetles that specifically colonise the Spanish firs, especially the weak specimens, as a consequence of the water stress and the high temperatures they suffer.

Locally, there are also a number of other issues at play, such as the position of flat stones, parallel to the ground but hidden, so that the surface area available to the plant for rooting is smaller than it appears and prevents it from taking in water. "When it transpires and evaporates more moisture than it receives, it dies a sudden death," he said.

"Decline is a phase that the forest goes through to control itself, there is a high density of trees and in times of stress the weakest die. This leads to the accumulation of the remains of branches and trunks in different phases," Quintanilla said. To this, the leading authority on this species added the fact that the pinsapo, after thousands of years of evolution, "uses its capacity for resilience". And the fact is that the change in the climatology gives more chances of survival to those that take root at a higher altitude and with better orientation, on the northern slopes, so that, in the long run, they will move higher up.

Despite the fears, the director of the national park is clear: "Overall, I wouldn't say that the pinsapos are more affected than other species; it is a climatic circumstance that has caused a lot of problems, whether it is due to climate change or other circumstances, time will tell." In the opinion of its director, the general state of health of the Sierra de las Nieves is very good. "We see the forest developing at its own pace," he said.

This is one of the first observations scientists make: the landscape is shifting towards a wider palette of native species. Pinsapos are mixing with holm oaks, which are better able to withstand a lack of water, and this is seen as beneficial because it helps to slow the spread of pests.

In this way, the gaps are being filled with plants that are better adapted to these changes, as is the case in Parauta, where junipers, which are more frugal and resistant, are sprouting in the lower areas. Meanwhile, the pinsapo continues to climb and conquer higher ground.

Helping the forest

Paths and fire prevention

Although the situation is not considered serious, the forest will get help from humans, especially to prevent fires. Another expert in the group is Javier Venegas, head of the technical office for forestry works of the environment agency Amaya, which is drafting two projects to be financed by the Sierra de las Nieves recovery plan, with a joint investment of 3.2 million.

One of the actions will consist of creating a new path, taking advantage of an old route, with three aims: to fight fire, to improve the phytosanitary situation of the trees and to provide another public access for visitors.

Another project will be aimed at favouring the strong natural regeneration that has taken place, so up to 30,000 tree protectors from previous plantations will be removed, although those reforestation sites where the vegetation still needs extra help will be reinforced.

Conclusions

Natural regeneration is stronger than tree loss

The two areas with the greatest deterioration are the pinsapo forests of Parauta and Yunquera, both below 1,200 metres altitude, and, as a study by the University of Jaén showed, the effect of drought and the increase in temperature is worse at lower levels than at peaks.

For the experts, this year is very reminiscent of 1995, the last year with such a high mortality rate. The main causes of death are water stress, which leads to sudden death, and the plagues of the beetle Cryphalus numidicus and the fungus Heterobasidion abietinum which kills them off. However, according to Quintanilla, this is all part of the system that the forest uses to adapt to the conditions, "as if it were a natural thinning".

The third National Forest Inventory in Malaga by the Ministry for Ecological Transition, reflects the most recent official data. The first column reflects the number of trees with a diameter greater than ten centimetres, a total of 2,985,982, while a further 3,262,454 were smaller. The total area of Spanish firs in the province is 2,962 hectares, with some six million pinsapos (an average density of 2,000 feet per hectare).

This is in line with studies by the Junta on representative sites, where a mortality rate of 20 to 30 per cent has been observed. But the fact is that the most affected areas still have 2,800 trees per hectare, i.e. a very high density, and that over the years it will end up being only 100 to 150 mature trees.

As for natural regeneration, data from the Junta gives a germination rate of 140,000 seedlings per hectare in the Grazalema pinsapo forest and 44,000 in the Sierra de las Nieves. The higher density in the former is due to the richer and deeper soil conditions and the abundance of rainfall.

Most of these seedlings will die over the course of their lives, reaching 2,000 to 2,800 trees per hectare by the age of 60. "As the forest ages, individual trees are lost. When there are high temperatures and low rainfall, there is higher mortality."

"We mustn't get used to seeing the forest as a fixed image, as if it were a garden," explained José López Quintanilla; "It is alive, it reproduces, it grows, it dies and there is a cycle that is structured by the conditions in which it lives."

"That's why I'm not so worried about this decline, because I see from the large regeneration that the future is assured, and that is the main objective we have in forest planning. Similar situations in previous years have already been compensated by spontaneous regeneration.

Trees are indeed being lost due to the lack of rain, although there is a lush regeneration of small pinsapos. The survival of the species is guaranteed.