The nuclear 'weapons' against cancer being developed in Spain

Teragnosis is a promising cancer therapy based on radioactive isotopes that is beginning to show "spectacular" results in tumours such as prostate cancer

Teragnosis. Remember this word. It is rare, but it will soon become a household name in the fight against cancer. Experts claim that it is one of the oncological therapies that will grow the most in the next few years. "It is going to become fashionable," stress the Real Academia Nacional de Medicina de España (Ranme).

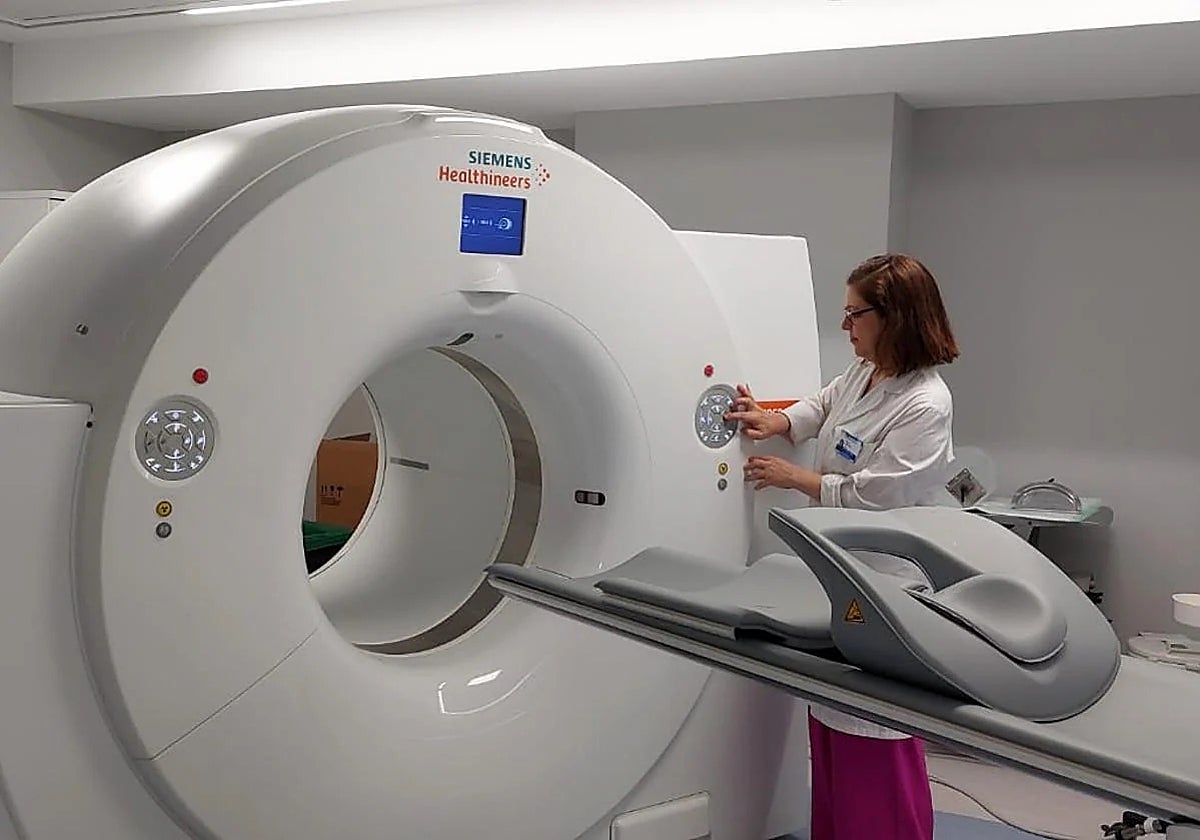

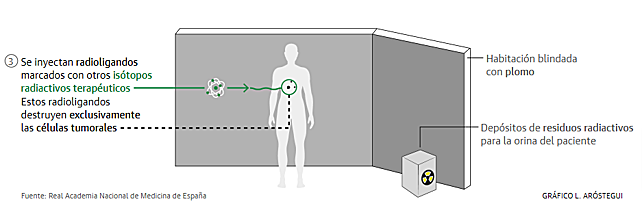

But what is teragnosis? It is a treatment based on nuclear medicine which uses radioligands, a kind of 'arrow' loaded with radioactive isotopes that are injected into the patient and which are first used to diagnose the tumour (diagnostic radioligands) and later to attack it from the inside (therapeutic radioligands).

In a first phase, these diagnostic 'arrows' 'see' the tumour molecules (similar to contrasts) and remain stuck there. By targeting these areas and thanks to PET-CT imaging technology, nuclear medicine specialists can see where they have 'stuck', i.e. where the cancer cells are located.

Zoom

Zoom

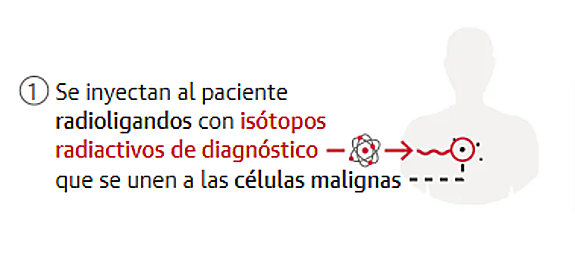

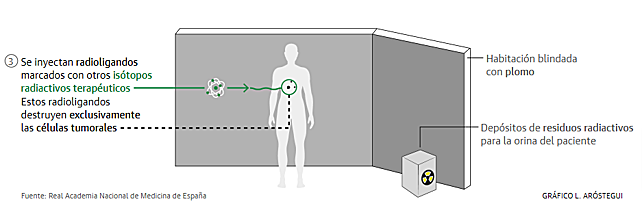

"In a second phase, once we have checked with diagnostic radioligands where these malignant cells are located, the same or similar radioligands are used, but marked with other therapeutic radioactive isotopes that destroy only these tumour cells without damaging the rest of the cells or healthy tissues," explains José Luis Carreras, emeritus professor of Radiology at the Complutense University of Madrid, academic of the Ranme and one of the 'fathers' of teragnosis in Spain.

Zoom

Teragnosis has been used since the mid-20th century against thyroid cancer, and for the last few years against other neuroendocrine tumours. But it has also produced "spectacular" results in clinical trials to combat advanced cases of prostate cancer, the most common cancer in men.

"It's going to be the fastest growing cancer therapy in the next few years," experts predict

In Spain it is not yet administered within the public health system because the ministry of health is still negotiating the price with the pharmaceutical company that manufactures the isotopes. In authorised treatments, patients are usually administered between four and six doses of radiopharmaceuticals, at a price of between 8,000 and 10,000 euros per dose.

Carreras has spent his entire professional life trying to introduce the most cutting-edge techniques in nuclear medicine into the health system, and he believes that teragnosis combines all the characteristics of preventive, predictive, personalised and precision medicine. "It is going to be the therapy against cancer that is going to grow the most in the coming years," predicts the doctor, one of Europe's leading experts in nuclear medicine.

María Nieves Cabrera, head of the teragnosis unit at the Hospital Clínico San Carlos in Madrid, explains that one of the advantages of this technique is that doctors only treat what they see. "We inject the patient with a radioactive substance to determine whether there is a specific fixation in the tumour cells we want to treat. That will be the basis for us to treat the tumour with a molecule similar to the one we have made the diagnosis with," she explains.

Several screens show a detailed panoramic view of the patient's entire body, where, thanks to diagnostic radioligands, information is obtained on the actual extent of the tumour. A multidisciplinary team then decides on the specific treatment based on therapeutic radioligands.

The administration of the isotopes takes place in a hospital room shielded with lead to protect against radioactivity. These rooms have special radioactive waste tanks that store the patient's urine for treatment before it goes down the general drain. "The patient does not go home until he or she has enough radiation to lead a normal life, although precautions must be taken during the following days, especially with regard to the exposure of children and pregnant women, who will be the most sensitive to radiation."

Against other types of cancer

At present, teragnosis is a minority treatment (neuroendocrine tumours are rare), but research is being carried out into its application, in addition to prostate cancer, in breast, pancreatic and lung cancers. Later this year, the unit headed by Dr Cabrera is expected to take part in a trial with another radiopharmaceutical that will probably be able to treat all types of tumours. "I am convinced that we are going to be able to broaden the horizon of therapy a lot," she says.

Along the same lines, José Luis Carreras believes that we are facing a "new hope" for beating cancer, including metastasised cases that have already exhausted all treatments. "In prostate cancer there are spectacular results. In very advanced cases, long-lasting complete remissions are being achieved in up to 25% of patients. And we have to bear in mind that in these cases there is no other solution, as they have become resistant to hormonal and chemotherapy treatments. When we are able to work on less advanced tumours, the results will be even better," says the expert.

Although the patient receives radioactive isotopes, teragnosis is better tolerated compared to the effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy "because the radioligands bind to the tumour cells and respect the surrounding healthy cells. It is at the level of the best tolerated drugs," says Carreras. This is why he believes that we are facing an "explosion" of this technique.

In fact, in countries with less regulation, a wide range of tumours are already being treated with teragnostics. "It will be possible to apply it to almost all types of cancer because they all have a suitable target to fix a diagnostic radioligand, and if we see that it captures it, we will treat the tumour knowing that there will be a response beforehand and attacking the cancer directly by putting the radiation (the therapeutic radioligand) inside the tumour cells. It's a great reason for hope," says the doctor.

Day hospitals and a plant in Salamanca

To carry out the diagnostic part of teragnosis, according to Dr Carreras, diagnostic equipment is needed (PET-CT, PET-MRI, SPECT-CT), which "fortunately is already available in most hospital Nuclear Medicine services". However, for the second therapeutic phase, in which the patient is treated, "more investment is needed from the national health system because it is essential to expand and adapt the existing treatment areas, although this would not really represent an excessively high investment", says the expert. Carreras is calling for the creation of day hospitals, similar to those that already exist for oncological chemotherapy. "The only requirement is that they have a system for collecting, storing and eliminating the radioactive waste emitted by patients in their urine and faeces in the first hours following the intravenous administration of the therapeutic radioligand," he points out.

Europe's most modern plant for the latest generation of cancer drugs is currently under construction in Salamanca. This plant, owned by the pharmaceutical company Novartis, will supply diagnostic radiopharmaceuticals, a substantial component of the oncological treatment of teragnosis. The factory will directly employ at least 20 qualified professionals and another 50 in indirect jobs.