Control freaks

THE EURO ZONE ·

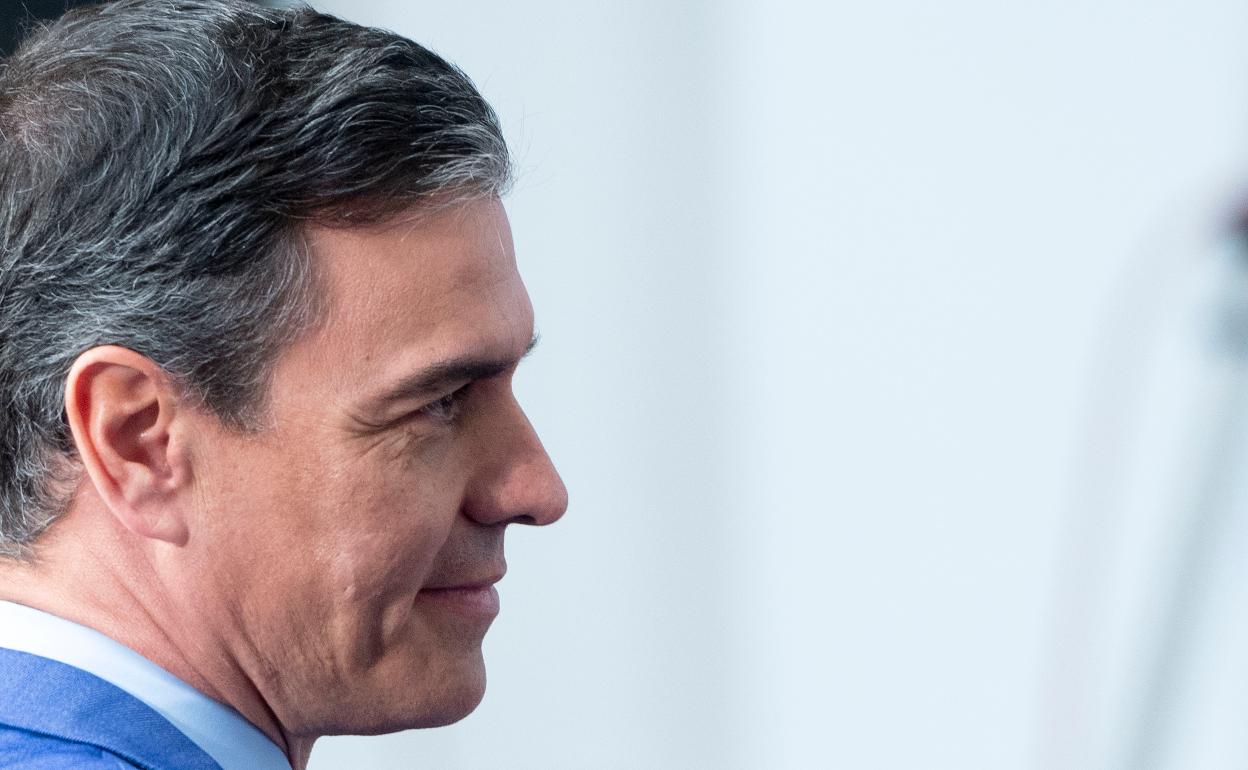

Some many questions regarding the recent allegations of digital espionage remain unansweredPedro Sánchez this week pledged to "strengthen judicial control" of Spain's national intelligence centre (CNI) in the wake of the phone-tapping scandal, but is this really what's needed? The intricate connections between the CNI, Spain's supreme court and defence ministry make it very difficult to answer that question, and even harder to apportion blame for the digital espionage, said to have targeted over 60 Catalan separatists as well as Sánchez and defence minister Margarita Robles.

Sánchez's promise of a more tightly controlled CNI follows the sacking last month of its boss Paz Esteban, the only woman to have held Spain's most senior intelligence job. A week before her departure, Esteban apparently told a congressional body that the CNI had tapped the phones of 18 Catalan separatists, but that it had had judicial authorisation to do so. This presumably means that the CNI had received approval from the Supreme Court, the intervention of which is required when fundamental citizens' rights are jeapordised by a proposed intelligence operation.

The question that needs to be answered is "Which individual(s) in what organisation ordered the phone-tapping against Catalan separatists?" Was it the CNI or someone in the ministry of defence, the government department to which the CNI is attached (after Sánchez switched it from the prime minister's department in 2018)? Given the political orientation of those targeted and the official neutrality of the CNI, the latter seems more likely - but in that case, why was Esteban fired and not someone from defence?

This question becomes even more puzzling when you recall the speech given by Robles a couple of weeks before Esteban was fired, in which she came close to admitting that the Socialist-led coalition had orchestrated the espionage. Yet Robles, who heads the defence ministry, kept her job.

If Sánchez had sacked someone from his own cabinet, it would have looked too much like an admission that the government was involved in espionage: firing Esteban, on the other hand, put the blame squarely on the CNI's shoulders. It's hard to believe, though, that the intelligence agency acted totally unilaterally in tapping the phones of Catalan secessionists.

The phone-hacking scandal and the resulting political crisis also prompt us to question, once again, the extent to which the judicial and executive branches of Spain's government operate separately.

It's not the first time this issue has arisen in the context of the debate about Catalan secession: when the Supreme Court handed lengthy prison sentences to nine secessionists for their roles in organising the independence referendum of 2017, many critics, not without reason, portrayed it as a weaponised arm of the executive. Sánchez might claim that the judiciary needs more control of the highest intelligence agency; but the real problem, perhaps, is that the executive has too much control over the country's highest court.