British author and Hispanist Giles Tremlett speaks out on Franco on 50th anniversary of Spanish dictator's death

In his latest book, the writer describes him as "dull and lacking charisma, but very ambitious and possessing great leadership skills"

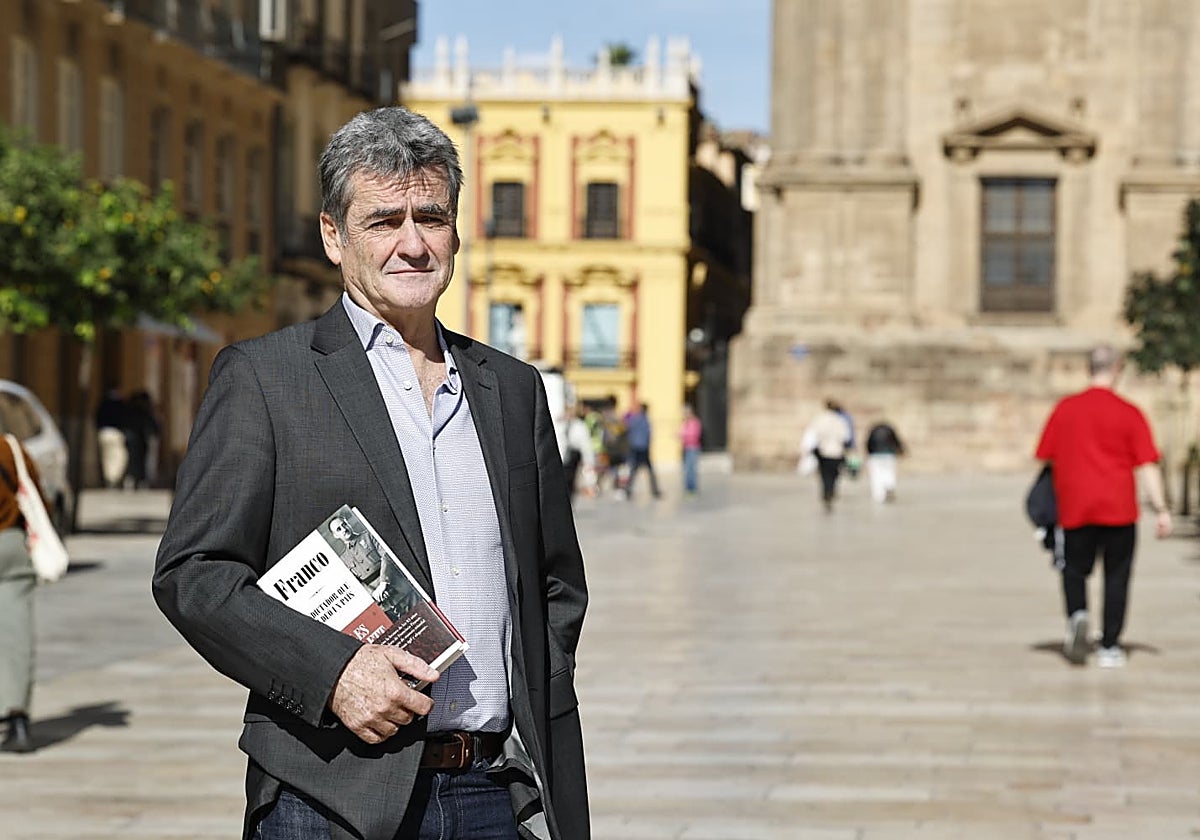

He is an Englishman and that gives him a perspective and some distance that a Spaniard would be unlikely to have on this matter. Yet even he has succumbed to the effect that writing or pronouncing Franco's name still produces. On the 50th anniversary of Franco's death, British Hispanist Giles Tremlett has published 'Franco: The Dictator Who Shaped a Country', a biography written from "empathy, not sympathy", in an attempt to understand the man beyond the pure black-and-white image. Yet Giles admits that, sometimes, depending on to whom he's writing, he is tempted to remove this title from his list of publications in the message to avoid causing offence. "It hasn't been overcome and I too have let myself be affected by it."

- Much has been written about Franco. What does this biography add?

- Well, I'm an English Hispanist and distance helps because I have nothing at stake at a personal level. It doesn't affect my family's Christmas dinner. And I'm more of a biographer than a historian, so I make an effort at empathy, not sympathy. I try to get inside Franco's head and understand how he thinks and why.

- He was a short guy, lacking charisma and with hardly any ideology. Have you figured out the secret of his success?

- That secret is based on three things. One is that he's not as mediocre as he's made out to be. Intellectually, yes, but in terms of command, of political manoeuvering, not at all. Secondly, he's an incredibly ambitious character. It's not that he wanted power, he wanted all the power, forever. And thirdly, a military man doesn't need charisma. If I'm a general, it doesn't matter that I'm short with a high-pitched voice, everyone has to bow down before me. Military charisma is all about here (he taps his shoulder, where rank and medals would be on show) and it doesn't matter what you look like.

"Franco never changed his mind, it was the Spanish people who had to adapt."

- These past few days I've had the book on my desk at work and many people have stopped to look at it with curiosity or surprise. We're still taken aback at seeing the name 'Franco' in large letters. Why?

- It's just that one doesn't so easily shake off the fear. There's a kind of inertia to that fear. Paul Preston talks about an early investment in terror, which refers to the years after the Spanish Civil War, the 20,000 executions and the brutal repression that followed. And it's an investment in the sense that, if you apply it at the outset, then you start reaping the benefits. It doesn't have to be so visible, so commonplace. And that's still there. On the other hand, what Francoism sought and achieved was the political apathy of the people, their silence. And finally, there's the silence of the Transition [Spain's move from dictatorship to democracy], that pact of forgetting lasted far too long.

- A recent CIS poll says that 21% of Spaniards considered Francoism to have been a good or very good period. Do you have an explanation for that?

- I think this figure has remained much the same since 1975. The problem today is that the lack of knowledge about Franco makes it a black-and-white debate. There's not much nuance. I think it's essential to understand, in vivid detail and not just like cardboard cutouts, who Franco really was. With the benefit of hindsight, we can now ask ourselves more subtle questions. Did Franco's regime influence the Transition? To what extent did Franco's regime influence and continue to influence Spain today, the events in Catalonia, the setting up of autonomous regions or even the Spanish monarchy itself?

- Do you have the answer?

- It's obvious that those who held the reins during the Transition were the Francoists. The King himself was one of them in that sense, he had received all the powers from Franco and he spoke of the legitimacy he inherited from that glorious uprising.

- Perhaps it was the only way to do it peacefully?

- Maybe it couldn't have been done any other way, but it was done that way and we have to take that on board. That's not criticism, it's not saying how bad the Transition was, but it must be said that it wasn't as perfect and it didn't start out in the immaculate state as it is so often portrayed.

Young people

- According to the same CIS poll, 19% of young people also believe that Francoism was good or very good. They didn't live through the Franco regime or even the Transition. How can that be?

- There's a very clear, primary reason and that is that we haven't taught them in school what Francoism and the Civil War were like. Something very similar is happening throughout the Western world with young people, especially young men, who are leaning towards the far right. And OK, it's a choice, but they have to be very aware that if their favourite word is 'freedom', as it said on the t-shirt Charlie Kirk was wearing when he died, then dictatorship is the opposite of freedom.

- What surprises you most about the figure of Franco?

- I'm surprised he was so boring. There are descriptions by his cousin, Francisco Franco Salgado, who was his aide-de-camp, of dinners at El Pardo Palace when the Prince and Princess of Monaco came to visit, and he tells of a deathly silence. Franco didn't bother to converse. But the most surprising thing is that he never changed his mind. The Franco of his early twenties is the same Franco when he died. Normally, things happen to us in life and we change. But he didn't, it was the Spanish people who had to change and adapt. And you had to survive, so you ended up collaborating with it in some way.

"We have not taught young people what Francoism was"

- Catchphrases like 'Make America great again', do they remind you of that period in history?

- In a way, yes. Franco was an ultra-nationalist. And so are the new right-wing populists. And what they always sell is a glorious past to which we must return. That's what Franco wanted to do.

- Is democracy in danger?

- It's always in danger because democracy contains the means to kill off democracy. We must always be vigilant.

- With this book, have you experienced firsthand those wounds that are still open?

- When I was a correspondent for The Guardian newspaper, I became very interested in historical memory. I went to villages and talked with people. I was very struck by the fear, the silence. That 'keep your voice down!'. And although I say I'm English and maintain a certain distance, I live in Madrid, I've been here for 30 years, I have my neighbours and, when I wrote this book, I was also thinking about them. I don't live outside of Spanish reality. So, it's true that I've always been aware of how difficult it is to talk about Franco, to put his name out there. I have it in my email now, because I always include a list of my books and, for the first time in my life, I have to think about whether or not to delete the cover photo, depending on who it's for, in case that person is going to be offended. Still, 50 years later and me, a foreigner.

- It's not over at all, is it?

- It hasn't been overcome and I too have let myself be affected by it.