The rise and fall and rise again of Malaga’s grape, raisin and wine industry

This year’s grape harvest has been affected by a mildew that has come about due to a disastrous combination of heavy rain and soaring temperatures, but it hasn’t been as catastrophic as the phylloxera plague of the late 19th century

This year’s grape harvest in Malaga province has been one of the most complex in recent times, marked by a dual scenario of climatic conditions that have, on the one hand favoured the development of the vines and good quality grapes, but on the other hand, the wet conditions followed by high temperatures have provided the perfect conditions for mildew to take hold.

In Manilva, the western Axarquía and the Montes de Málaga, losses of up to 80 per cent of the harvest have been reported by some vineyards. In the Antequera area some vineyards have been unaffected and others have lost up to 50 per cent of their crops. In the eastern Axarquía area and the Serranía de Ronda the presence of this fungus has been minimal.

But this isn’t the first time that the province’s grape harvest has been affected by disease and in fact the mildew has not been as catastrophic as the phylloxera plague that affected vineyards across Malaga and much of Europe in the nineteenth century.

The origins of the province’s wine-making tradition date back to the late Middle Ages, when agriculture and livestock farming were the main economic activities and winemaking played an important role. For centuries, Malaga wines were celebrated and sought after in the most distinguished markets in Europe and were consumed in London, Amsterdam and Hamburg and beyond. By the eighteenth century Malaga was Spain’s biggest exporter of wine.

A thriving trade

Trade not only impacted the local economy but also led to the emergence of a thriving bourgeoisie, many of whom were of foreign origin, who controlled the land and large estates. The two main varieties of grape were Muscat and Pedro Ximénez.

Malaga’s wines were highly acclaimed in Russia. In 1791 the then ambassador to Moscow Miguel de Gálvez, uncle to Bernardo de Gálvez, the American Independence hero born in Macharaviaya, presented Empress Catherine II with several cases of Malaga wine, which she liked so much that she declared it tax-free in her kingdoms. Similarly Tsar Alexander III was said to be very fond of Malaga wine. During the first third of the 19th century, much of the province continued to thrive thanks to its grapes and especially the popularity of its wine and raisins.

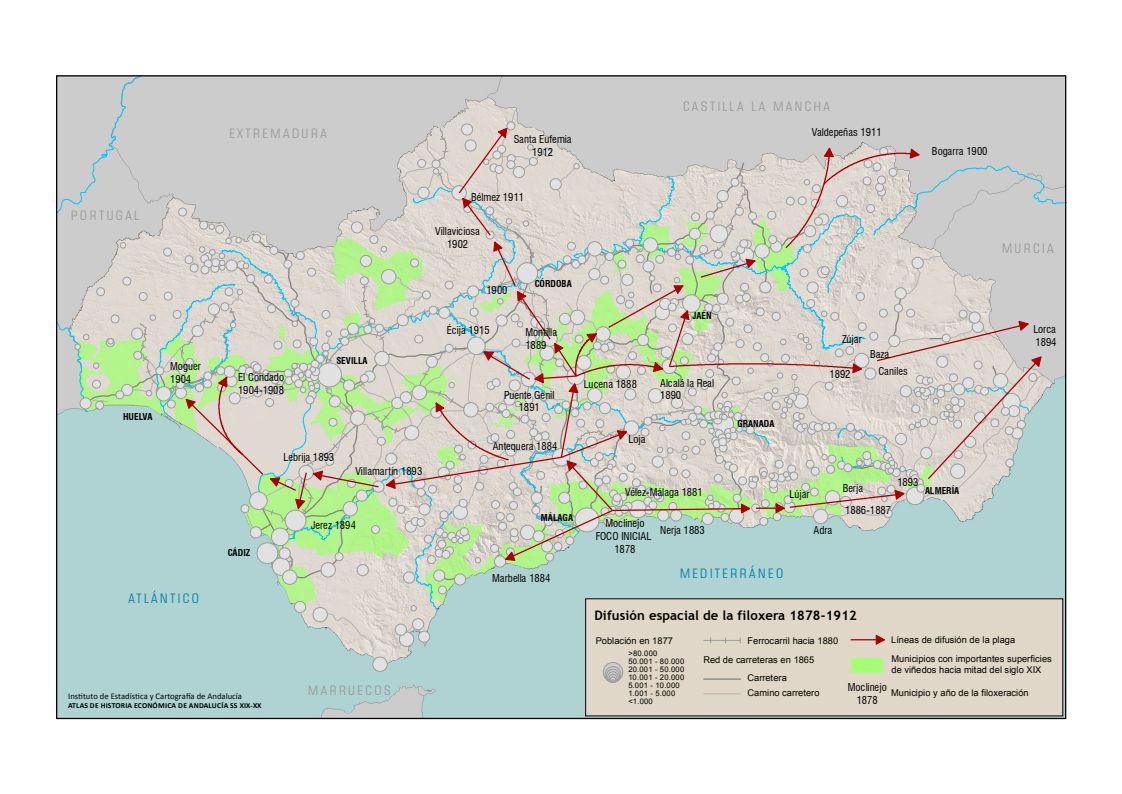

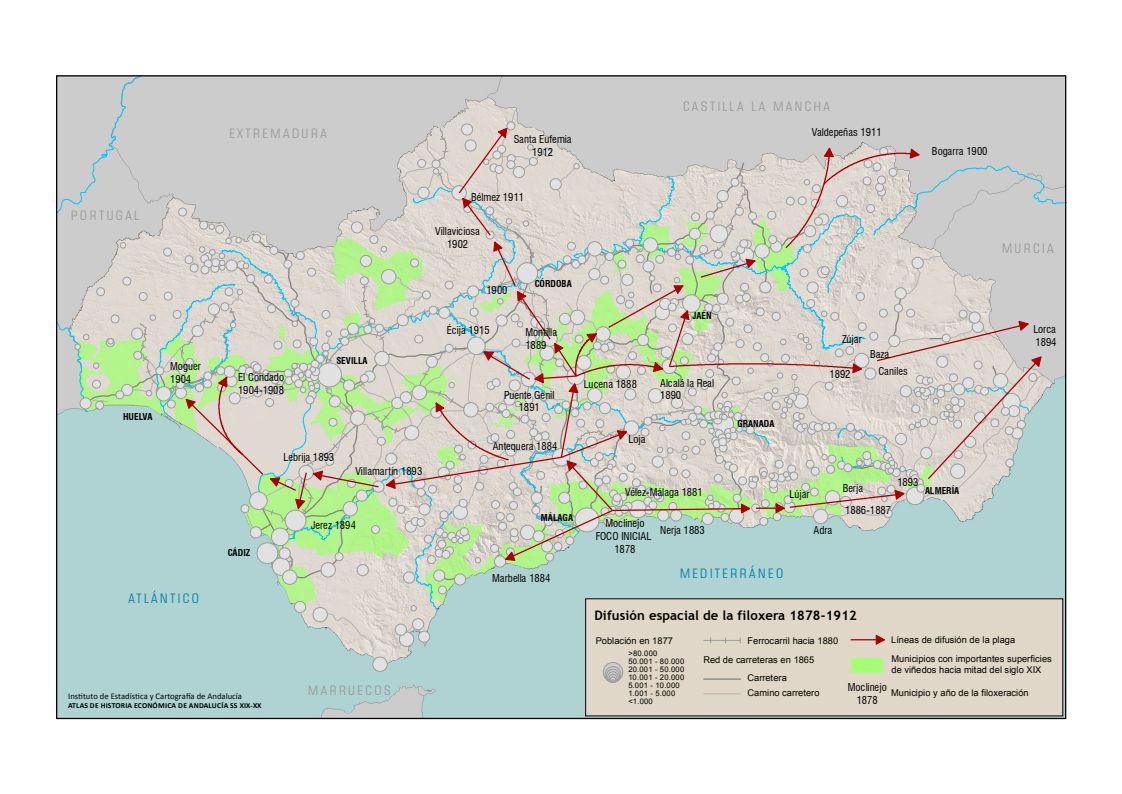

However, disaster struck when phylloxera was detected on La Indiana estate in Moclinejo in July 1878. Although it is believed that the disease first appeared in Ronda and Moclinejo in 1874 and 1875, labourers and landowners at that time attributed the loss of vines to the poor quality of the land or the severe drought of previous years rather than this new disease.

Zoom

The parasite had first been identified in Europe in 1863 when vines mysteriously started drying up in France. In 1868 Professor Jules Émile Planchon came to the conclusion that this tiny insect had most likely come over from the Americas.

It had two characteristics that set it apart from other pests: it spread quickly and not only infected the plant but killed it. It was the beginning of a catastrophe that would destroy almost all of Europe’s vineyards over the course of half a century. From Moclinejo phylloxera quickly spread to nearby vineyards and by August 200,000 vines had been infected.

Carried by the wind, the spread of the ‘wine plague’ lasted for decades. Regions that had not been affected waited, terrified, for its arrival. It was also recorded in Catalonia in 1879 and Valencia in 1900.

Experts

Many experts travelled to Malaga to study the plague in an attempt to contain it and there were numerous requests for financial aid, but it was slow in coming and by 1886 there were no Muscat vines left. Two years later the same happened with the Pedro Ximénez vines.

With the harvests completely destroyed, the wine and raisin trade collapsed and economic activity came to a standstill. The situation was so dire that by 1894 the government stopped collecting taxes and contributions in some areas.

In 1930, despite many efforts to resume cultivation, there were only about 36,000 hectares of vineyards. The lack of work in the Axarquía and other areas led to depopulation as people sought work elsewhere and some even went abroad.

It wasn’t until the end of the 1990s and early 2000s that winemaking started to see a resurgence in Malaga province and the Sierras de Málaga Designation of Origin DOP), a protected geographical indication for wine varieties in Malaga, was created in 2001.

DOP regulates the Pasas (raisins) de Málaga and in 2017 the Axarquía’s grape growing and drying process was recognised by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations as a globally important agricultural heritage system (GIAHS).

Despite the mildew that has affected some areas this year, Malaga province’s grapes, raisins and wines are once again sought after in international markets. This is thanks to both the region’s popularity as a tourist destination and the work of its Spanish and foreign-owned wineries