Photo trio

Nostalgia in three clicks

Georgina Oliver

Thursday, 30 December 2021, 13:44

Paul Strand (NYC 1890 - Orgeval 1976), at the Carmen Thyssen Museum. Brassaï (Brasso, Transylvania 1899 - Beaulieu-sur-Mer 1984), at the Museo Picasso. Jean-Marie Périer, famous for his cool pics of 1960s pop and rock stars, at the Centro Cultural de la Malagueta, housed in Malaga’s spruced-up bullring, within steps of the Pompidou centre.

Three solo shows focusing on era-marking photographers - sharing a common link with France - form a scintillating trilogy, and the good news is that all three of these must-sees continue till next April. “Foto aficionados” will be over the moon.

Straight in the eye

It’s no cliché to say that Paul Strand “changed the face of portraiture”; also considered a ground-breaker in his approach to nature and cityscapes, Strand is remembered as a pioneer of “straight photography”, known as “photographie pure” in his country of adoption.

“Pure” or “straight” photography is the ancestor of the frontal hard-edged photographic codes that have come to be associated with conceptual art. Popularised by his mentor, Alfred Stieglitz, it marked a deliberate departure from the hazy Impressionistic “Pictorialism” previously in vogue. Suddenly, beauty was in the hands of the camera-holder. The idea was to reinvent it, pushing the limits of reality. Hence the title of the exhibition at the Thyssen Museum: Paul Strand. La belleza directa. (In English: Paul Strand. Pure Beauty.)

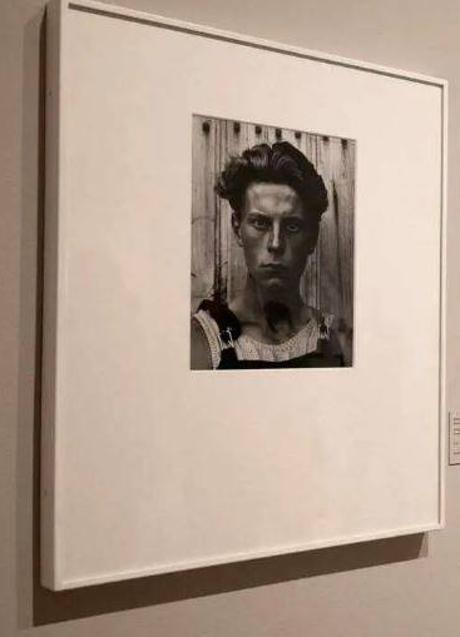

Paradoxically, beauty is not the word that springs to mind when we light upon some of this eminently Francophile American photographer’s black and white pictures. Among these: Blind Woman, New York, 1916 and Young Boy, Gondeville, France, 1951. Much as Paul Strand’s figureless compositions possess - be they architectural or bucolic - a unique abstract dimension, his iconic human portrayals function like archetypal representations of the human condition. Universal symbols, rather than personal mementoes.

That unforgettable French boy sporting dungarees and a sleeveless knitted vest looks us straight in the eye, yet for all its intensity, his gaze might as well be blank; no attempt whatsoever is made to seduce the onlooker. It’s up to us to fill in the blanks. 1951? Farmhand or fisherman? Think beyond the frame. WWII is relatively recent. What have those eyes witnessed?

In this riveting head-on image, there is no visual hierarchy between the rustic wooden door or window shutter in the background, the boy’s clothes, his shock of hair, his facial features, and glaring stare… – the latter perhaps suggesting contained violence. We’re not sure.

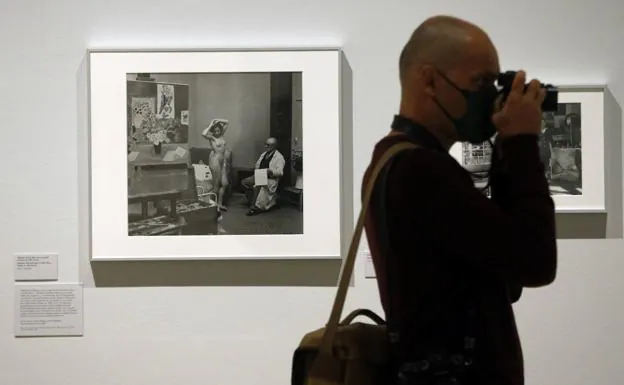

Brassaï's world

A further treat awaits photo buffs visiting Malaga during the festive season. The Picasso Museum has conjured up a spectacular overview highlighting multiple facets of the talent of Picasso’s friend and biographer, the French-Hungarian photographer, filmmaker and artist, Gyula Halász aka Brassaï. Entitled The Paris of Brassaï. Photographs of the City Picasso Loved, this extensive display places Pablo’s Paris in context; featuring works by Picasso, Bonnard, Braque, Léger, Dora Maar (…), along with documents such as musical scores and theatrical programmes, it walks us through the Paris of the 1930s and 1940s we love to revisit. Paris by Day. Paris by Night.

Brassaï’s artistic contribution to the creative effervescence of the “City of Lights (and shadows)” - sculptures and drawings; his interest in graffiti… - stops us in our tracks. Paul Strand and Brassaï were trailblazers. Both of these world-renowned photographers branched out into avant-garde filmmaking; both of them having picked the same home away from home: “La France”.

Zoom

While Paul Strand’s journey led him to France via Mexico, New England, the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, Italy and Ghana; from McCarthy’s America to Europe and Africa; and, ultimately, to Orgeval - his final resting place, on the southeastern outskirts of Paris… Brassaï set out for Paree with his parents at the age of three, from his native Brasso (then part of Hungary, now situated in central Rumania). Young Halász studied art in Budapest, and was enrolled in the Austro-Hungarian cavalry during the First World War, before working as a journalist in Berlin, where he entered the Academy of Fine Arts, so he did not settle in the French capital until 1924.

Another “Strand-Brassaï connection” is their mutual fascination with the eyes of their subjects. For Brassaï’s take on Pablo Picasso’s “black diamonds”, turn to the “museopicassomálaga” website’s audio guide: Why do they appear to be larger than life? What lies behind his apparently “fixed, mad, haunted” gaze? “It is the eye of a visionary prepared for perpetual astonishment.”

Yeah, yeah, yeah

Admission to Jean-Marie Périer’s “Ab-Fab” retrospective presented in the pristine white corridors of the revamped Plaza de Toros is absolutely free - and, I’ll let you into a secret… Few people can have enjoyed it as much as I did.

I was just a kid, a pre-teen (8, 9…??), when Périer rose to fame, in the early 1960s, as the photo-chronicler of France’s “yé-yé” popster movement. On holiday in Le-Touquet-Paris-Plage - particularly on rainy days… I flicked through the fanzines he contributed to: “Salut les Copains” and its girly equivalent “Mademoiselle Age Tendre”.

Jean-Marie’s chic‘n’cheeky, chic‘n’sharp… tangy-toned photos were the life and soul of those mags, filled with the vitality of sixties fash.

“JMP” has always claimed to steer clear of classic reality - and, to be sure - whether photographing Mick Jagger, or the international Haute Couture gang, past and present - he has never erred from that objective… I’ll say no more, just… Go, go, go… Go see it…!