The long battle against illiteracy in Spain

Almost 600,000 people in Spain don't know how to read or write, although the figure has fallen by 160,000 in the last five years

ALMUDENA SANTOS / LUCY NEWBY

Lunes, 2 de septiembre 2019, 12:07

"I needed an air conditioning unit and a fridge so I went to the shopping centre," says Antonia, a woman from Extremadura. So far, nothing out of the ordinary. But Antonia is illiterate and something as simple as shopping with her credit card becomes an obstacle course for people like her. To get the card, which had a limit of 300 euros, the bank made her sign papers that she "didn't understand" and after buying the appliances, the bank claimed 1,200 euros from her.

The case ended up in court, which eventually stopped Antonia from having to pay the money. The defendant's lawyer, Fernando Cummbres, argued that because she could not read, she could not understand the smallprint.

DATA

-

1.25% of people in Spain don't know how to read or write, according to the INE report 'Población de más de 16 años por nivel de formación'.

Illiteracy in Spain was a scourge until the second half of the 20th century. In 1936, the year the Civil War began, 25% of Spaniards were illiterate. The extension of education gradually reduced the rates, but even today, 581,600 in Spain, 1.25% of the total population, do not know how to read or write, according to the report on population over 16 years old by level of education, published by the National Statistics Institute (INE).

Numbers decrease

The number of illiterate people decreases year by year in Spain, mainly because the elderly, the demographic with the lowest level of education, are dying. Five years ago, 745,100 people were illiterate in Spain and in 2018 there were 614,200. Illiteracy is a problem which affects more women (387,900) than men (193,700), and there is also a difference between regions: Melilla tops the list with 3.7% of people being illiterate (3,200), ahead of Ceuta at 3.64%, Murcia (2.75%), Extremadura (2.7%) and Andalucía (2.16%)

On the other hand, the Basque Country, with a 0.34% illiteracy rate, Cantabria (0.35%) and La Rioja (0.38%) are the autonomous regions with the lowest illiteracy levels.

The fight against illiteracy owes much to adult education centres, which have evolved over time. They began as places for older people who had not been able to finish basic education, but now most of those using them are foreigners.

Adult education

"Nineteen years ago when I joined the EPA [adult education centre], most of the students had a lower level than secondary education (ESO). They were women of retirement age, over 60, and came from fairly humble backgrounds," says Belén Soroa, an ESO teacher at an adult education centre in San Sebastián.

This teacher explains that illiteracy is still kept a "secret". "Many of the women who attend classes do not want to be seen in their home environment as illiterate," explains Soroa. "They are capable of changing villages and going to places where no one knows them, in order to hide it. They feel that they are stigmatised and don't want it to be known," she says.

"The centres have changed a lot," agrees María Jesús Alonso, a former student at an adult centre. "Now we are looking for more school graduates looking for work." Alonso entered this school to get the secondary education certificate, since he only had primary level. After achieving it, he attended computer classes.

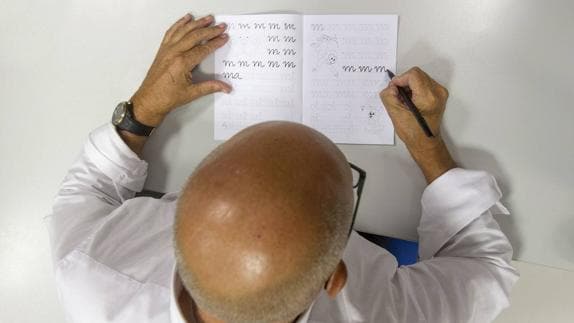

Adult education courses last two years and their content is "a little lighter" than in secondary schools, says Soroa. "The subjects covered are adapted to those who are attending classes. As a teacher, you can't give students the same subject matter as a 10-year-old, even if they're both learning to write," she says.

How does Spain compare globally?

On an international level, Spain and the rest of Europe are some of the most literate countries in the world. According to UNESCO, 99 per cent of European and North American adults (15 years and older) are literate, in contrast to eighty-six per cent globally.

However, 750 million of the world's adults still remain illiterate, two thirds of whom are women, with 49 per cent of the world's illiterate population living in South Asia.

UNESCO findings show huge disparities between factors such as region, gender and also age, with the elderly being much more likely to be illiterate than youths, emphasising an increase in global literacy over time.