Your eyes will play tricks on you at the new exhibition by Carlos Cruz-Diez at the Pompidou

The Venezuelan artist explores chromatic phenomena: colours that are seen but aren't there; others that seem to move; and paintings that change as you move

Regina Sotorrío

Malaga

Thursday, 28 March 2024, 15:35

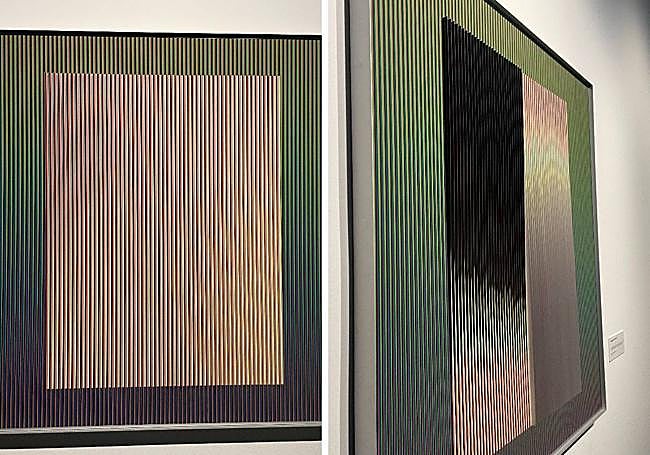

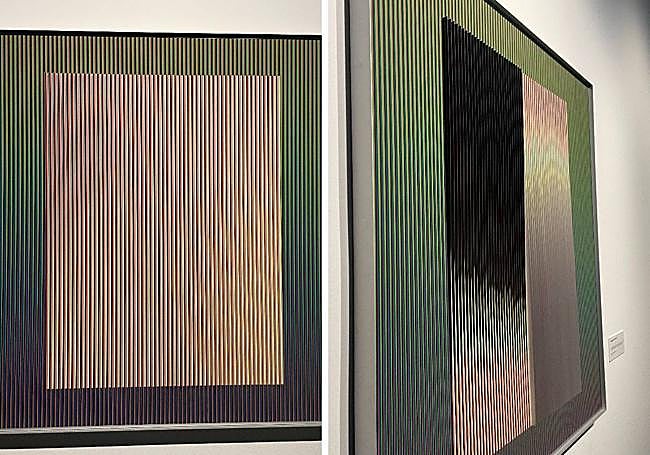

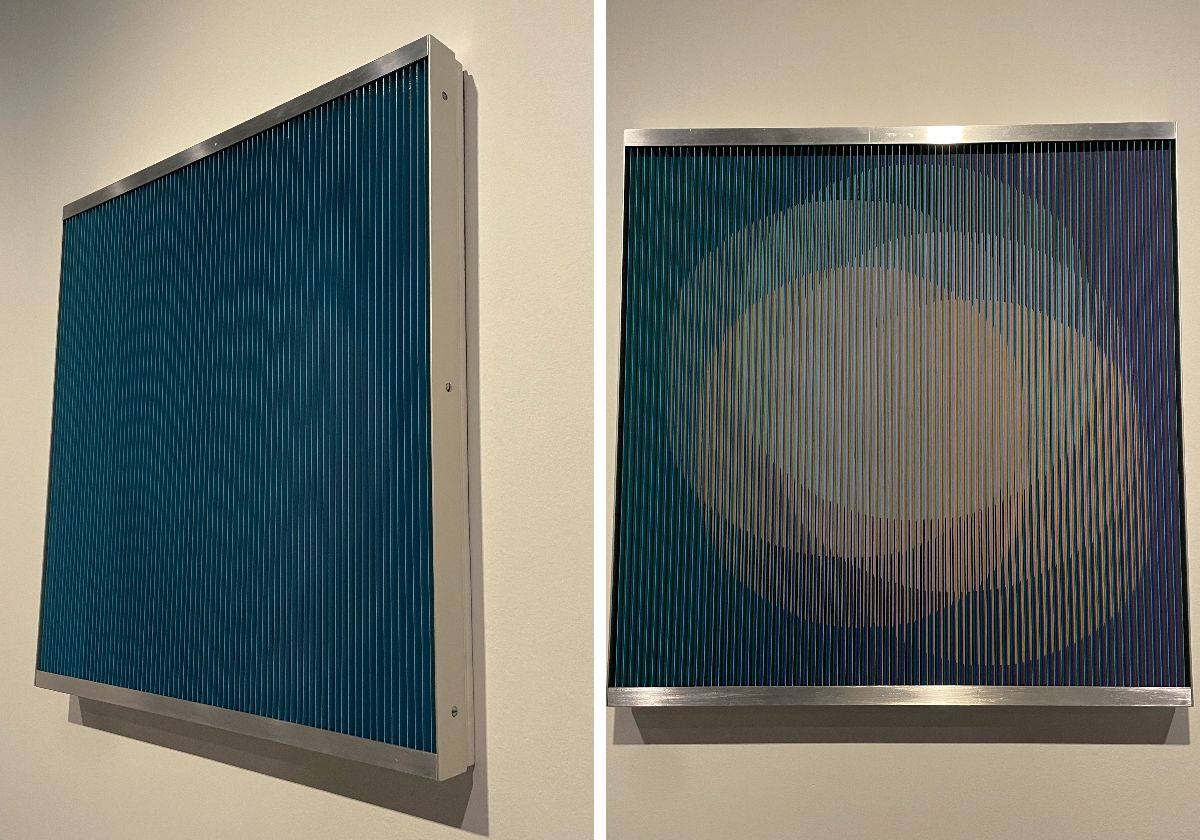

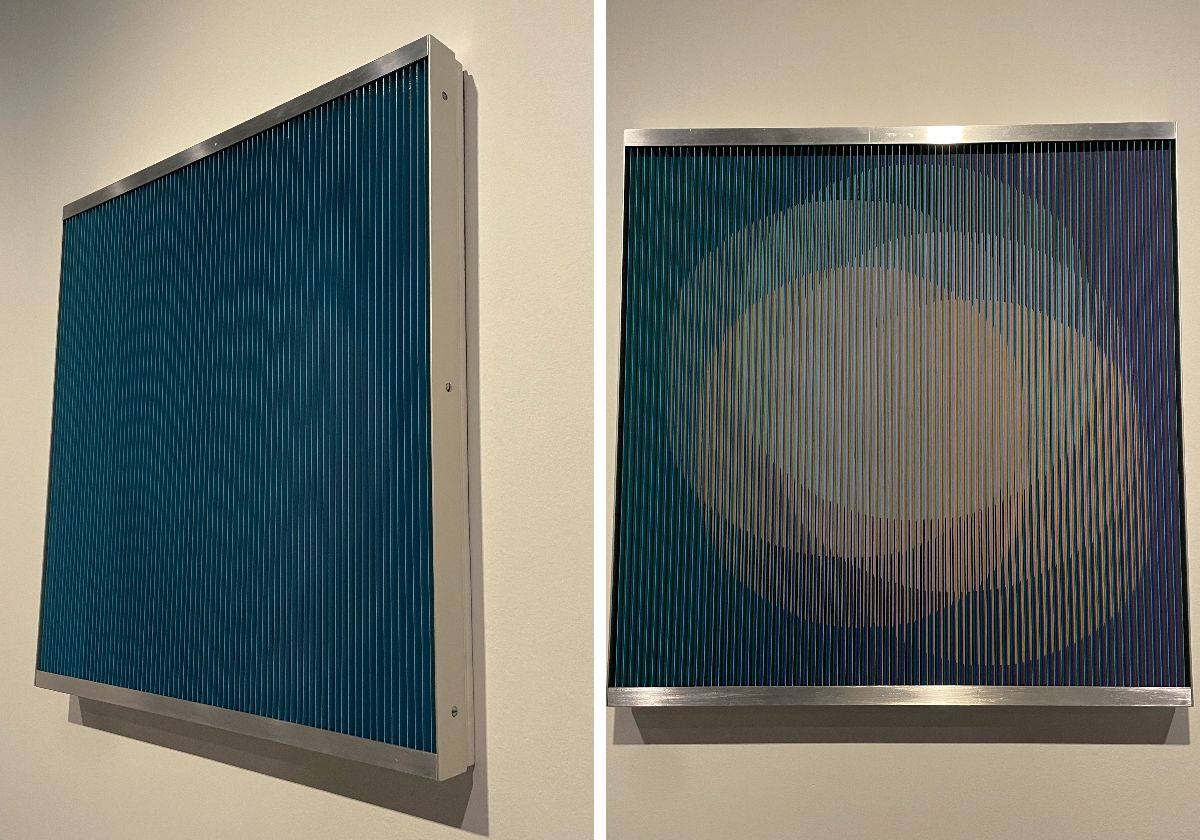

This is not your typical art exhibition because, to begin with, what you think you see is not what is really there. It may seem to you that one of these works of art is painted yellow, but no - step in closer and you will not find that colour present at all. You will believe that the colours are moving in another painting, but the lines actually remain static. And the first piece you see when entering the gallery, a monochrome work in blue, is not really like that: as you move around it, circular shapes will suddenly appear. The Pompidou Centre Malaga is playing around with optics in its new temporary exhibition, running until 29 September, to beguile visitors, an exhibition that pays homage to optical art as explored so intensively by the Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez (1923-2019).

"All his life he tried to demonstrate that colour is autonomous, that it does not need any form to exist. We always say red apple, blue sky, green leaf.., but that's not the case," states his son Carlos Cruz Delgado as he stands before almost forty works by his father made from straight lines.

He was his father's right-hand man for 50 years of studies, since 1959, and his technical support for his "inventions". All Cruz-Diez's work is based mainly on two optical effects. Firstly, chromatic induction, the changes in shade, colour and clarity that the eye experiences when it sees different colours simultaneously. The other is the after-image, the image and colours that appear in our eyes after a period of exposure to the original image or colour.

Optical art

On that basis, Cruz-Diez explored different colour-related phenomena in several series of works that demand more than the usual viewing by gallery visitors: they must move around the work, go in close then zoom back out several times, looking at it from different perspectives. In short, they must "socialise" with it, "making optical art the most people-centric of the arts", argues curator Michel Gauthier.

Zoom

"Here, you choose from which viewpoint you contemplate the artwork, and that varies the painting. There won't be two spectators with the same experience. "There's a whole infinity of paintings within each painting," explains Gauthier in front of one of the many 'Physichromies' that occupy the room. Thanks to thin vertical strips of plastic arranged perpendicular to the plane of the painting, the shapes and colours of the paintings change as the person observing them moves in front of them. Those strips conceal some colours and reveal others with the movement of the viewer.

In movement

The effect achieved in 'Cromointerferencia Mecánica' is fascinating: the colours come to life and move. However, it's not real. The viewer experiences a visual interference, a 'moire' effect, which destabilises vision with chromatic waves that seem to oscillate. Cruz-Diez discovered that by moving a transparent sheet with lines over another support also with lines of colours arranged in a similar way, chromatic interferences appeared and the colours changed. In another piece, the artist manages to replicate that phenomenon without any mechanical component, only with the viewer moving around the artwork.

In the 'Color aditivo' series, the artist ingeniously confuses the human eye once again. From afar, you'll see a painting with vibrant colours, with vertical lines of an intense hue. However, if you approach the artwork, you'll see that there are only horizontal lines. These pieces are based on the dual phenomenon of optical mixing and colour irradiation. When two planes of colour come into contact, a third colour appears in the area where they converge. Sometimes, that virtual colour spreads uniformly across the entire surface where they meet. In other instances, it produces a halo.

Zoom

In another section of the exhibition, two works with a yellowish tone hang. You see it, but it doesn't actually exist either. This is what's called chromatic induction, related to the phenomenon of retinal persistence: when the eye contemplates a blue plane and then moves away from it, it will see yellow, its complementary colour. Naturally, this occurs in two phases, but Cruz-Diez managed to compress it into one by measuring the relativity of colour perception. In the paintings at the Pompidou, only white, black, and blue are actually painted; yellow is a virtual colour.

Cruz-Diez was a pioneer in creating sensory environments. He designed three cabins with the colours red, blue and green to offer a two-step experience. First comes the 'chromatic bath': participants have their usual viewing colour palette drastically reduced as their retinas become saturated by the single colour surrounding them in the chosen cabin. This is chromosaturation. For the second part, after spending some time in the cabins (it depends on each individual), the eye will perceive the space that surrounds it with the complementary colour of the one in which it has been immersed: yellow for blue, red for green. and green for red. This is known as retinal persistence.