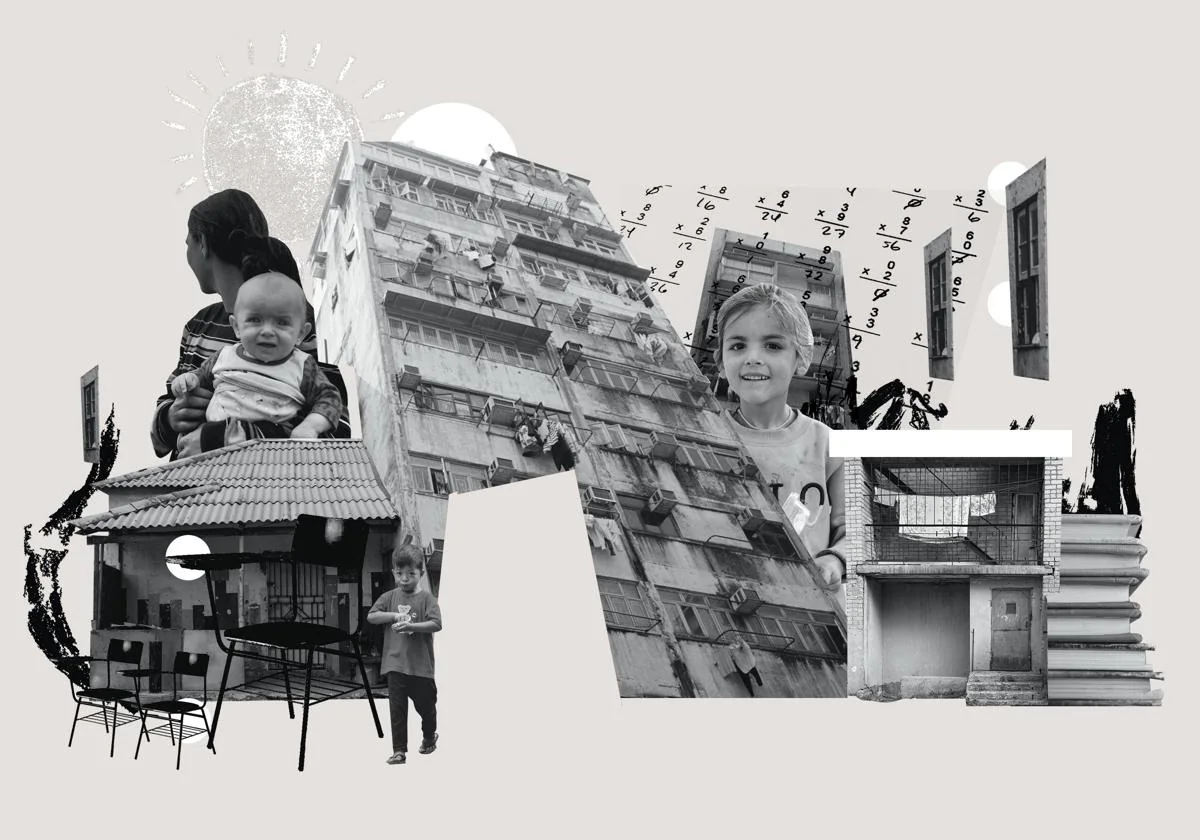

Is it possible to climb the social ladder in Andalucía? It seems difficult, but why is that?

The debate rolls on about whether socio-economic success depends on merit or is predetermined by place of birth or social class, but in this region in the south of Spain some 37% of children born into poor households remain in the poverty trap

Our faith in equality of opportunity and meritocracy can all too often be shattered by the extent to which being born into one household or another determines a child's future. Poverty continues to be inherited, as do titles of nobility or property. And this, which is something that everyone believes to be the case, is laid out in black and white in a study by the Andalusian institute of statistics and cartography (IECA). Worse still, the stats show that this is more the case in this region than in the rest of Spain.

This is the survey on intergenerational transmission of poverty which is included as a special module in the IECA's 2023 living conditions survey. If we compare its results with a similar study carried out at national level by Spain's INE (national statistics institute), these clearly show that the indicators for the perpetuation of poverty across generations are more than ten points above the Spanish average. In short, the social ladder in Andalucía is grindingly slow at giving people a boost.

For example: of all those aged between 25 and 59 who spent their childhood in homes with a poor economic situation in Spain, 25% are still at the same level as adults, but this percentage rises to 37% for Andalucía. Other indicators are the same or even worse: 51% of people in the region who, as adolescents, did not have their basic school needs covered (books and school materials) now live below the poverty line. Nationally this percentage is 16.5 points lower at 34.5%.

Furthermore, the intergenerational transmission of economic conditions goes hand in hand with that of educational rank: people born to parents with a low level of education (primary education or lower) are less likely than average to study a degree or higher vocational training and are more likely to remain stuck at a low level of education. In Spain, only 36.2% of respondents whose parents have a low level of education go on to higher education and 11% of them do not even reach secondary education. But this correlation is stronger in Andalucía, where the percentage of higher education graduates among those with lesser-educated parents is less than 30% and where 15% do not go beyond primary school. On the other hand, being born to highly qualified parents is practically a guarantee that a good educational level will be attained: almost 80% of children of parents with higher education qualifications also obtain this level of qualification.

Poverty and low educational attainment go hand in hand

Both variables, poverty and low educational attainment, in turn influence each other, they even feed off each other. Therefore, among Andalusians who were born into homes with a low level of education, the poverty rate is 30.4%, almost double that of those who grew up with parents with a higher level of education (16.3%). This gap, again, is greater in Andalucía than in the rest of Spain.

At the University of Malaga (UMA) there is a research group called public economics and equity which is dedicated to studying inequality, poverty and social exclusion, as well as public policies aimed at addressing these problems. Elena Bárcena, Professor of Applied Economics, heads up the group and confirms that social mobility "is lower in Andalucía than in the rest of Spain." In other words, the social lift does not work so well in this region and, therefore, it is more difficult to escape from the socio-economic vagaries of life. "All the indicators of intergenerational transmission are more intense in Andalucía, both in terms of poverty and educational level," says Professor Bárcena.

So, why is this happening? Bárcena suggests: "There are three factors that determine this phenomenon: the education system, the labour market and public aid aimed at combating poverty." If we take into account that Andalucía is among the worst-placed regions in terms of educational results and school failure, that its labour market is marked by being of a more temporary nature and lower pay, and that benefits for vulnerable families are lower in amount and coverage than in other regions, it is not difficult to understand why the poverty cycle is more intense in this region.

Housing as an aggravating factor

To these classic factors used to explain why history repeats itself for those who live in poverty, Bárcena adds one that has gained prominence more recently, especially in Malaga, that of housing. "With prices rising so sharply, many families have to spend a large part of their income on a mortgage or rent to avoid being left out on the street, leaving them little margin to pay for food, books, computers, extracurricular classes or sporting activities for their children."

Social organisations have long been warning that social mobility, like inequality, worsened across Spain in the great financial crisis of 2007-8 and has not recovered since. The report 'Intergenerational transmission of poverty' by the Foessa Foundation (funded by Cáritas Española) lists the causes: "The high levels of inequality, which peaked in 2016 and are far removed from the situation before the economic crisis, the critical situation of the education system with high dropout rates, the lack of opportunities for young people who neither study nor work, and the ineffectiveness of social spending aimed at reducing poverty, which only registers about 25% improvement in social benefits." This is one of many reports completed by the foundation, founded in 1965 and consisting of senior researchers from 30 plus universities in Spain, that examines how Spanish society is developing and progressing, with a focus on social exclusion and social change.

The "poverty trap"

All these conditions, the report continues, lay the foundations for the "poverty trap", which is the name given to the accumulation of difficulties that a person who has spent his or her childhood in a family in a situation of poverty has to face throughout his or her life. Experts also speak very graphically of "sticky wages", because of the difficulty involved in climbing up from the lowest rungs of the socio-economic ladder, hence the social lift being a similar concept to the very British phrase of 'getting a leg-up in life'.

Professor Salvador Pérez-Moreno also belongs to the UMA's public economics and equity research group. He focuses on child poverty, which in Spain reaches an inconceivably high level for a developed country. Sadly, once again Andalucía leads the way: 41% of children under the age of 16 live below the poverty line. These are children who did not choose the home where they were born, who are growing up in the midst of deprivation and, if nothing is done, will have a high probability of continuing to live a precarious life to the end of their days.

"There are a number of negative manifestations of poverty during childhood: reduced cognitive development, malnutrition, school dropout, low self-esteem, obesity, high levels of stress. All these issues become disadvantages when facing the world in adulthood and many of these children will have difficulty accessing the labour market, will have less stable jobs, more fragile family and social relationships, lower learning capacity and shorter life expectancy," stated Pérez-Moreno.

The expert continued: "We are not aware of the seriousness of the problem, of the enormous personal, social and economic cost of child poverty." The problem is serious, he argued, "for ethical and human rights reasons." Moreover, it is serious from a purely economic point of view: "There is a high consensus among academics about the impact of poverty on economic efficiency. There are studies that put the cost of poverty at 4 or 5% of GDP." He considers it an "absolute waste" to let the potential of an important part of a country's human capital go to waste.

The cost of poverty

Turning the argument on its head, Pérez-Moreno concluded: "Decisively tackling the problem of child poverty would make it possible to advance both equity in the present and efficiency and economic prosperity in the future." Investing in children, he believes, would help to break the vicious circle of poverty and build a "virtuous circle between equity and efficiency," because "more equal and more cohesive societies are also more prosperous and efficient."

So, how is this achieved? The first thing that comes to anyone's mind - experts included - is education, the social lift par excellence. Still, the experts warn that it is not just enough to improve the education system, since student performance does not depend only on how good the school is: individual factors, family background and educational policies are also involved. There is an OECD study that says that in Spain, among these factors, it is the family that is the most relevant predictor of educational performance.

As poverty is a multidimensional phenomenon there is no magic wand to fix this and many things have to be done at the same time. "It is a complex problem that needs to be tackled in a holistic way: addressing the different aspects that are the roots of poverty and manifestations of poverty so that the negative consequences suffered by children in vulnerable environments are less harmful and the scars they leave behind are less," he argues.

Pérez Moreno offers two specific prescriptions. The first and main one is to improve childcare benefits: a benefit in which Spain has "a certain anomaly with respect to neighbouring countries because it is smaller and covers fewer people." Child-raising allowances have proven to be "very effective" in reducing child poverty. The second: guaranteeing free access to early childhood education for families with limited resources.

Universal child benefit?

Elena Bárcena is also in favour of increasing aid for vulnerable families, both in terms of the amount and the number of beneficiaries. Organisations such as Unicef, Save the Children and the Plataforma de Infancia are calling for more: a universal benefit per child up to the age of 18. Such benefits already exist in many countries, including 23 of the 27 EU member states. Professor Bárcena cites the case of Poland, which has managed to reduce its child poverty rate by 40% in seven years.

Yet why a universal benefit? Proponents argue that universality effectively removes many of the barriers and exclusions that prevent income-capped benefits from reaching precisely those they are intended to reach - that is, the poorest households.

This is the case, for example, with the minimum vital income (IMV) in Spain, the basis of which has had to be revised on several occasions and even so has a small number of beneficiaries compared to the number of households that, according to the stats, live below the poverty line. "The IMV is a step forward and helps to alleviate the effects of poverty, but it is not generous enough to lift these families out of poverty," said Bárcena.

Publicidad

Publicidad

Publicidad

Publicidad