Rural Spain - 'This village would be lifeless without its bar'

The region of Castilla y León came to the rescue of small village bars last year with a 3,000-euro grant. Jairo’s bar brings life to the 150 residents of Bayubas de Abajo, in Soria

José Antonio Guerrero

Madrid

Friday, 9 May 2025, 15:43

Without a bar, a village dies. "Where are you supposed to spend your time if there’s no bar nearby?” says Juan José Oliva, 73, who has been mayor of Bayubas de Abajo, a village with just 150 residents, for three decades. Many parts of rural Spain are grappling with isolation and emptiness - local bars are far more than just a place to serve coffee or a bottle of Mahou. They are the beating heart of the community, the place where everything happens.

The local bar is where neighbours catch up, laugh, chat and sometimes gossip. It's where messages, medicines, letters and even the latest Amazon parcels are passed on. It's where people notice if someone hasn’t turned up and raise the alarm if needed. It’s where locals come together for a card game to stay connected. In short, the bar isn’t just a place to drink - it’s a true social network, a real life version of Facebook, and the community’s central gathering point.

For the small, scattered villages that make up rural Spain, such as this one in the northern region of Castilla y León, the local bar is the life and soul of the community, the glue that holds its few residents together.

“In small villages, there has to be a bar so that people can come together and socialise, chat while playing mus [a card game], or gossip and criticise the mayor; nothing surprises me anymore,” jokes Oliva.

Zoom

Like many other local mayors, Oliva, who has spent his life working in agriculture, welcomed an initiative brought in last year by the Junta de Castilla y León to offer grants of up to 3,000 euros to village bars. The funding helps to cover running costs, such as water, electricity, gas, internet and TV subscriptions, ensuring that these vital community hubs keep going. The scheme supports bars in villages with fewer than 200 residents, recognising their crucial role as social centres and providers of essential services, as well as their ability to combat loneliness.

This point was emphasised by a regional minister of Castilla y León when launching the initiative last year in Santa Espina, a small village in Valladolid with just 74 residents. Its mayor, Luis Miguel Puerta, describes the bar as the “epicentre” of village life.

“In our bar, we sell bread. If the pharmacist delivers medicine and the resident isn’t home, it’s left at the bar. If the podiatrist visits, we organise the appointments at the bar. And if the instructor for local arts can’t make it, the session is held at the bar instead. If you need help, you know there will always be someone at the bar who can lend a hand. It’s these everyday services that people in small villages value the most,” Puerta explains.

Castilla y León

3,260 villages with a population of fewer than 200

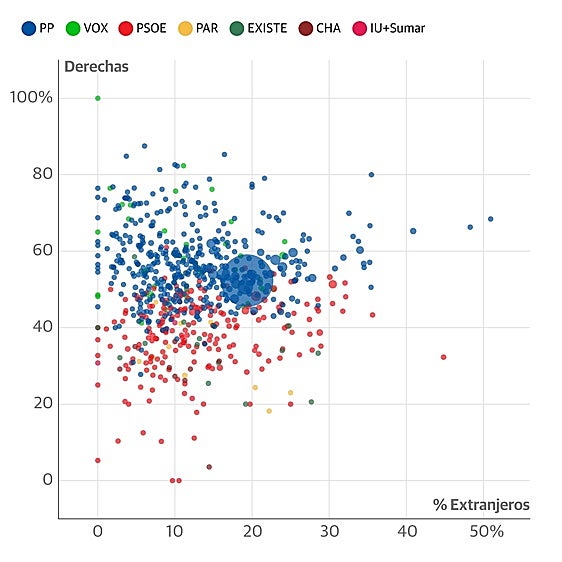

Castilla y León is one of Spain's regions most affected by rural depopulation. More than 3,200 of its municipalities have fewer than 200 inhabitants. In Soria, one of the least populated territories, there are 147 villages with less than 200 residents - that's 76 per cent of the province.

Yolanda, 61, has run the pub in San Cebrián de Mazote, a village in Valladolid with 100 residents, for the past 22 years. She echoes Puerta's sentiment: “There aren’t many of us here, but we love the bar,” she says. “In the bar, there is no such thing as loneliness. We keep each other company, especially in winter when there are just a few of us about.”

Zoom

The 3,000-euro grant, as expected, brought a big smile to Yolanda’s face, as well as to Jairo’s, the 40-year-old Colombian who runs the only bar in Bayubas de Abajo. Oliva, as mayor, lets him use the presmises rent-free, on the condition that it stays open every day of the year from 11.30am to 11pm, except in the winter when it closes a bit earlier. At that time of year, the temperature often drops to minus ten degrees and darkness sweeps over the streets like a black hole. Both the mayor and his villagers prefer to retreat to the warmth of their homes during the winter.

Long Sorian winters

Jairo is one of the 25 Colombians who have arrived in Bayubas over the past four years to work as resin harvesters in the vast pine forests surrounding the village. He took over the bar by chance. His sister, who had been running it, decided to return to Colombia to look after their sick mother. Oliva offered the premises to Jairo, who agreed to take on the role of managing the bar, though he didn’t give up resin tapping, which remains his main source of income.

He says, “The bar on its own doesn’t bring in enough money for me to send back to Colombia,” to support his wife and three daughters, who still live there. When he’s not behind the bar, his friend Leidi, also Colombian, covers for him.

“In summer, it’s busier, but the winter is long and hard, with only about 40 euros in sales a day,” he explains. “In winter, it’s all about getting by, and I know I’ll spend many hours bored behind the bar. But this place is more than just a business - it’s a social hub.”

The bar is in a prime location, right opposite the town hall. It’s spacious, clean and well-organised, with bottles of Soberano, Anís del Mondo and Johnnie Walker neatly lined up next to a television and a little Spanish flag. Inside, there are six tables, plus another half dozen on the terrace.

Free wifi is available for those who ask and several radiators are heated by a wood-fired boiler that’s lit from October to May. There is no food menu, except during the Santa Águeda festival in August. The snacks are limited to a plate of olives or crisps and peanuts, with an extra treat of torreznos (pork scratchings) at weekends, which Jairo prepares with a Latin twist.

“Without the bar, Bayubas would be even more isolated. I think it keeps the village alive,” says the Colombian, while Dani, the local secretary nods in agreement. “The winters here are brutal, and if it wasn’t for the bar, the villagers, most of whom are elderly, wouldn’t leave their homes. At least they have place to meet up and spend the afternoon playing cards,” adds the secretary.

Jairo also mentions the 'I’ll leave it at the bar' service, where the bar becomes a drop-off point for parcels and post. “We end up acting as delivery drivers without even realising,” laughs the resin harvester, who appreciates the peace and security he found in Bayubas. “Here, you can leave the bar open and nothing will happen. Do that in Colombia, everything will be gone in five minutes.”

"It lifts your spirits"

By 2pm, the pub begins to fill up with more customers. The 'vermouth hour' (pre-lunch) and 'sobremesa' (post-lunch) are the liveliest times of day. In one corner, a group settle down - Jairo knows nearly all of them and their usual orders. The personal touch is assured - another advantage of the bar.

The bar quickly becomes a hub of voices, discussing everything from the low price of resin this year, to praising the work of the local doctor or gossiping a little about a neighbour. “If you’re not there, they’ll soon have something to say about you,” jokes Adela, 63, who adds that in November, when the cold and darkness take over the streets of Bayubas, it’s comforting to spot the "warm glow" of Jairo’s bar. “On those dark nights, that light is a real comfort. You know there is somewhere to go, and just knowing there is someone inside is reassuring,” she explains.

“The bar lifts you out of the winter blues. A village without a bar is a cemetery,” says Santiago, an 81-year-old who was born in Bayubas. “The bar also provides protection to the community. If someone’s been missing for a couple of days, you worry, go to their house and ask about them,” he explains.

Afternoon coffee time is when the card games begin. The women head out for a walk (there are fantastic trails that wind through the pine forests and lead down to the Duero River), and on their return, they stop at the bar for a “cafecito” and a game of 'brisca'. Afterwards, the men usually take over, sipping 'chatos', bottles of beer and nibbling on bowls of nuts as they stretch the hours until each one returns home, and Jairo turns off the light. “See you tomorrow. We’ll meet at the bar.”

Invest in bars, not festivals

The bar in Santa Espina, a village in Valladolid, was where the Junta chose to announce its incentive for these businesses. For Luis Miguel Puerta, mayor of Santa Espina, it is complicated to keep these local spots open when they aren't bringing in enough money. Therefore, the mayor was glad to receive the grant, which could keep these bars open - maintaining social hubs which are vital for small villages.

"This money is better spent on bars than on festivals, which only come around in the summer," says Puerta.