The second-hand bookshops in Malaga that have a tale to tell

In the bustling city centre there are a few havens for bookworms where you can enjoy browsing through used, antique and just old, dusty books... But, in addition to coming across a rare read, the booksellers themselves also have many interesting stories to recount...

In the second-hand bookshops in Malaga the stories of their owners live on. In some cases the germinating seed for the business was a literary collection inherited by the entrepreneur himself. In others, the first to be sold were books that they themselves had treasured because they were collectors. Maybe they had to get themselves out of financial difficulties or a job-hunting impasse, but they started selling, even if in the process they felt as much pain as if having a limb amputated. Still, it is the same pain that they continue to suffer now because they are selling books that they have bought, individually and in person. Such purchases do not come from the large print runs of the new titles that publishers release; these copies tend to be scarce, sometimes rare. There are also examples of another kind of romanticism: a love that led to crossing the Atlantic, the lack of love that led to crossing it, and a used book franchise that comes to the rescue of economic survival back in Spain.

Now these establishments feed off the lives of those who inherit a library and have no place to put the books and no taste for the particular titles that have fallen into their hands. Maybe they are all about history, for example, and the inheritor prefers crime novels. They also depend on those who are moving house or premises, for the movers this turns into an excuse to let go of dead weight. That said, antiquarian booksellers are very discriminating: they don't buy by weight, they analyse whether these volumes are saleable on the open market. So, for example, the bookshop Librería Códice asks the seller to WhatsApp them photos of the library collection for sale, and shop-owner Enrique Consuegra knows just by glancing at the spines whether the books are of interest to him or not.

But there is not just one market. And this is also where the backstories of the very necessary third group of players enter the stage that is the antiquarian bookshop. These are the buyers, who incidentally are not always readers. On the one hand, there is the clientele that looks for books simply as an object to be collected, an antique. In many cases they will not even read their contents, nor even open them for fear of damaging them, although they will know all their technical details, such as the type of paper, the binding, who was responsible for them and which artist designed the illustrations, as well as the vicissitudes that each copy has experienced throughout its centuries of history. On the other hand, there is the market of pure readers, who limit themselves to good titles, well-translated, buying only good editions.

So, what is the profile of those who buy in second-hand bookshops? It depends. At the Librería Anticuaria Antonio Mateos they explain that it is mainly "educated people of a certain age", from 50-plus. Some even come from overseas to look for the treasures that this small shop is known to have, including a professor from an American university who visits them year after year.

At Códice, a bookshop more dedicated to books as literary works, when it opened its doors decades ago most visitors were in their forties, but nowadays it is frequented by octogenarians as well as young people in their twenties. And the clientele has been enriched, says Francisco Soler of Abadía, by tourists looking for job lots of Quixotes, books about Spain and Malaga and Lorca's poetry.

The best-selling used books are novels. But also books on philosophy, especially among young people calling in at the weekend, says Carmen Ocaña of Re-Read. Self-help books have their own particular, and large, audience: it is cheaper to buy a book, especially if second-hand, than pay for a therapist. And esoteric titles are all the rage. In any case, all these places are oases in the midst of the city's hubbub.

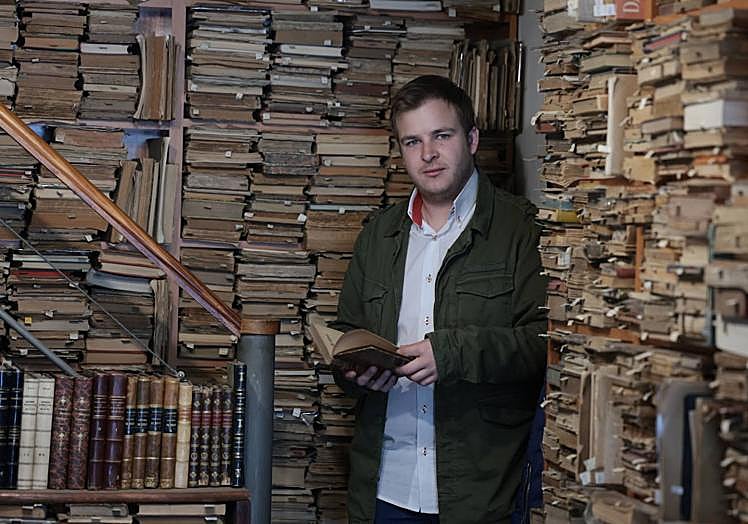

Librería Anticuaria Antonio Mateos

"The ones we like are the rare ones: an Alberti first edition, volumes with lithographs by Picasso..."

This story dates back nearly ninety years when, in 1938, four generations ago, the first Antonio Mateos of the family line opened a shop in Calle Liborio García (now in Calle Esparteros). It was in the middle of the Spanish Civil War and books - like everything else - were scarce. He took the stock he had accumulated while working as State Controller of the railways and put it up for sale in the literary city par excellence, Barcelona. There he came into contact with booksellers, toured the 'encantos' (fleamarkets) and filled entire railway carriages with books when he moved to Malaga. He kept them in a warehouse in Calle San Telmo and sold them, as well as in the shop, in kiosks in the Plaza de la Marina. During those early years the founder of this bookshop travelled around Europe in search of literary gems and old books, such as first editions of the Generation of '98 (late 19th-century Spanish writers) and copies of literature from Spain's Golden Age.

Antique books - sold more as objects than as reading material - are also the speciality of the fourth generation to take over the shop. His name, like his predecessors, is Antonio Mateos, and he graduated in Art History two years ago. "He likes the business", says his father, who still finds it difficult to let go of the bookshop, his passion: "I grew up in the midst of books, there are thousands of books in my house. My son has played with his toy cart shuffling around piles of books."

"The ones we like are the rare ones: an Alberti first edition, volumes with lithographs by Picasso.... For example, we have a French magazine from 1909 with two drawings by Picasso from when he signed as Pablo Ruiz", he says. "We want unusual books and we want to share them around. We avoid later editions." Among the 20,800 volumes they treasure, they pick out some more examples: manuscripts on the Inquisition, royal signatures from the Catholic Monarchs to Charles IV, books they obtain by buying up entire private collections and bidding at auctions. "The truth is that it's hard for us to get rid of what we buy," he says, alluding to his attachment to a catalogue made up of books that are mostly over a hundred years old, and which cover all kinds of subjects, including black magic, another hobby of the youngest in this family of booksellers.

He makes a few digs at the city's politicians and institutions: he has in his possession the act of constitution for the Cervantes Theatre, in which no official body has shown any interest. Neither have they shown any interest in Francis Carter's 'Journey from Gibraltar to Malaga', which he confesses they keep hidden because they absolutely worship Carter's hand-painted illustrations, including the Cathedral with its two towers, anticipating something that never came to pass. Another non-starter is the document that set in motion "the grandfather of the coastal train".

But the jewel in their book-collecting crown, naturally being the most expensive book too, is 'De las cosas memorables de España' by Lucio Marinelo Sículo, on sale for 5,000 euros.

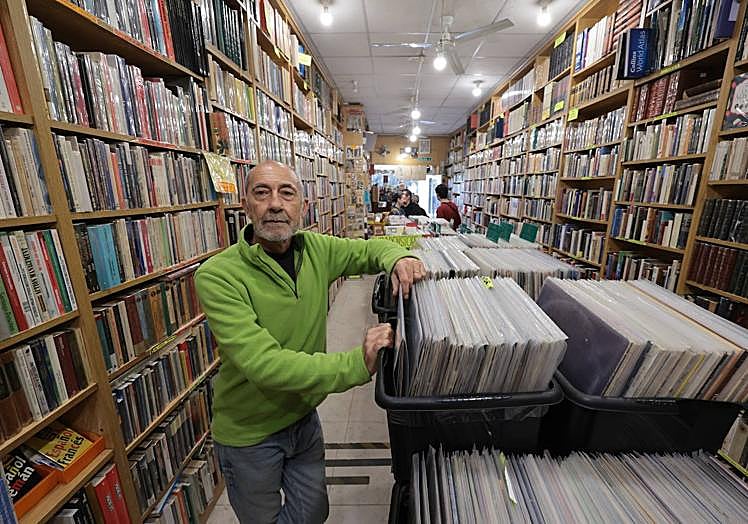

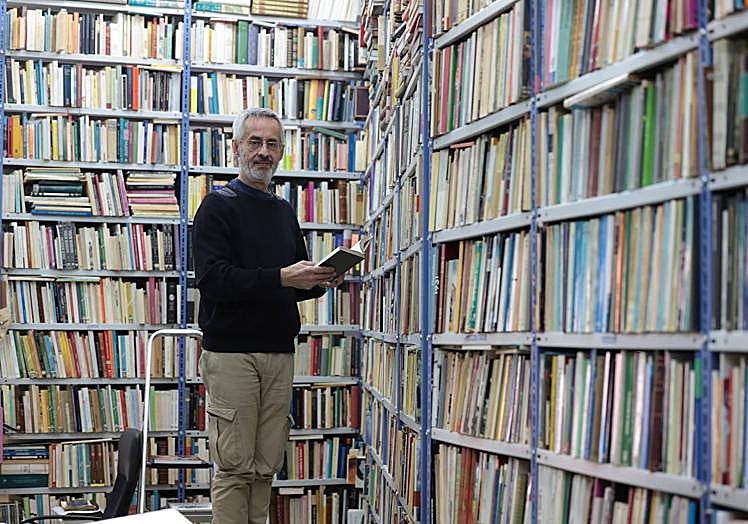

Librería Códice

"I'm very happy to work here. I could rent out the premises and sell online from a warehouse, but I like the contact with people"

The origins of Librería Códice came in the form of an inheritance of 20 to 30 boxes with around 3,000 books inside that the father of Enrique Consuegra, the bookshop's owner, received from his deceased brother. A year later, it was his own father who died. And so, several decades ago, Consuegra decided to set up the bookshop with those first copies, which included the classics of Spanish and Russian literature. Enrique claims that, over time, the pleasure of having accumulated so many copies becomes a burden. Nevertheless, in addition to the books and comics sold to him by those who inherit a collection or move house, he has also added vinyl records to his stock.

Between the 10,000 books he has in his shop on Calle Casapalma and the more than 200,000 he keeps in a warehouse, he has collector's gems such as the TBOs (aka tebeos - a funny children's magazine full of short stories issued weekly in Spain from 1917) from the 1950s in perfect condition, which sell for 8 euros a copy, like the one that a regular customer of 81 takes as we talk with Consuegra. This bookseller insists he does not have a book fetish: he buys books for the shop, he does keep some of them, but confesses that he doesn't have many at home. His philosophy is that the books have to "circulate". This way he does not experience what he has found to be very common in the collections he buys: there are many repeated titles, people buy the same book again because they don't remember that they already have them or that they have already read them.

But he does respond to the ideal of the bookseller who strives to remain close to his customers. And in this regard he is adamant about being so. The premises in Calle Casapalma where this second-hand bookshop is located is owned by Consuegra: "I'm very happy to work here. I could rent out the premises and sell online from a warehouse, but I like the contact with people. Besides, we know that if anything closes around here, it becomes a bar..." It is also true that the fact that he does not have to pay rent makes it easier for him to maintain this establishment in the heart of the city, a stone's throw from Plaza Uncibay, where the tourists gather and the cafe terraces are packed.

Librería Abadía

"People think that being surrounded by books makes you smarter, but this also causes stress"

Some female tourists are looking for 'The Little Prince' by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, and a Turkish boy on tour in Europe asks for Spanish literature accessible to his limited knowledge of the language and gets 'The Prince Dethroned' by Miguel Delibes. To a large extent, says Francisco Soler, owner of Abadía for a quarter of a century now, his customer base is now foreign: "The business with tourism has become more interesting because of the variety of people and stories. Spanish is an interesting language."

Soler was always a reader and collector of books, especially novels in general and comics, to which he later added volumes on his speciality, hispanic philology. But he became unemployed - he was a teacher - and so he set up a second-hand bookshop in Calle Comedias (now in Calle Tejón y Rodríguez) with his collection of 4,000 to 5,000 books for sale. He felt, he says, a kind of castration. This temporary solution to his economic survival lasted so long because he realised that he really liked the contact with the public.

Although so many years after he first raised the shutters he feels almost the same as he did at the start of all this: the books he sells are the ones he has bought, and they are not those of a conventional, chainstore bookshop that brings together the latest novelty or new editions in large print runs. His books are sometimes rare, unique, always in short supply. In fact, he doesn't buy just anything that's on offer - he is selective. He doesn't want books that are uninteresting or unsaleable because they are already in every house, like 'Da Vinci Code', or those that no longer have an audience due to social change or those that were the fruit of a fleeting boom. But there is a lot of variety, as the price range shows: his stock ranges from three euros to several hundred for the most interesting and scarce titles, among which an 18th-century edition of 'Las siete partidas' by Alfonso X stands out.

Now, short of space and eager to buy more, he has the entire catalogue at a 50% discount. And that diverts the conversation to an analysis of the business. He says that he has always been able to make a living from this second-hand bookshop. Still, he comments that he sells less now than in the early 2000s. It is also true that the situation is better than before the pandemic.

Does he feel frustrated by the literature that people sometimes buy, even though he is a specialist in the subject? "A bookshop lives by selling ordinary books," he answers diplomatically. In reality, he says, masterpieces are few and far between. Perhaps, he adds, people read more now than they did years ago, but the reading is syncopated, they only read short paragraphs, the headlines or what fits in a tweet. "Let's see what kind of people are going to be in a world where long texts are no longer read", he muses.

In this calm oasis, the bookseller is aware of the magic surrounding his trade: "People think that being surrounded by books makes you smarter, but this also causes stress."

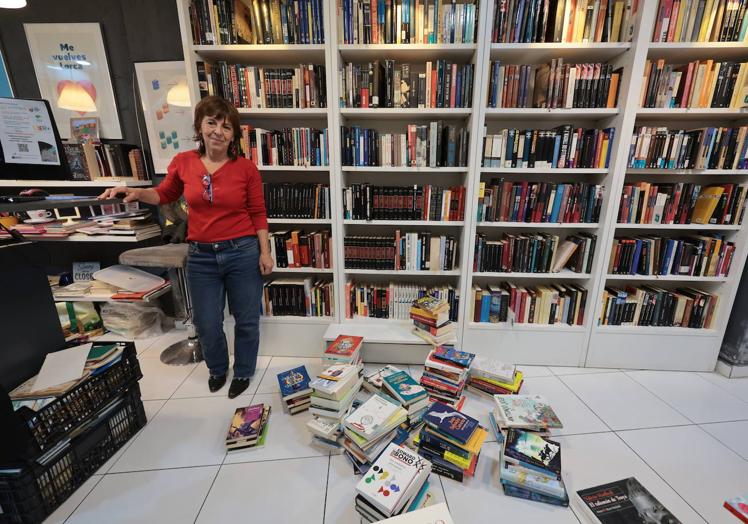

Librería Re-Read

"People have to read what they feel like reading. A good book is the one that sells"

Carmen Ocaña and María Azuaga are a mother-and-daughter team that have been running Re-Read on Calle Victoria for a decade, following Ocaña's return to Spain after a frustrated love affair that had taken her to Buenos Aires. She heard about a second-hand bookshop that was to open in Madrid and wanted to open more franchises. Although she had lived in Cadiz before crossing the Atlantic, she chose Malaga as a larger book market to open her own shop. "We opened the bookshop as a way of making a living. I had always liked reading, but I didn't know how the business worked. The model fitted in with our philosophy: we are in favour of second-hand clothes and that it is possible to have access to culture even if you don't have much money," says Ocaña.

During the conversation with SUR, customers and clients enter the shop and help to reveal how the business works. Raquel and Sergio come in laden with books to be sold in the shop. They are, in general, works published from the year 2000 onwards - they buy up modern editions and themes - and the dual owners pay them 25 cents a volume. They then mark them up for sale, although the more you buy, the cheaper each volume gets. Ocaña makes an appeal to those who can help her to get rid of her book stock so she can restock: she needs books on Malaga, its history, geography and brotherhoods, and she also wants to have more poetry. And to their reading clientele: they want this space to be the opposite of a temple, they want to hear laughter and conversations about the books.

But Ocaña doesn't identify with the air of mystery surrounding bookshops and booksellers: "This is a very physical job," she says. Her daily routine includes a lot of cleaning and a lot of sorting and stacking books on shelves. But she does admit that the best moment of her job is when books arrive: "I'm the first one to choose."

She is grateful for how much she has learned: she had never read comics before and now she likes them. She knows how to appreciate publishers and a quality edition and the importance of a good translation. Also, not to be classist about books: "People have to read what they feel like reading. A good book is the one that sells." Still she confesses that she is curious about what others read: who hasn't fallen in love with someone momentarily because of the book they were reading? Or quite the opposite, of course.

¿Tienes una suscripción? Inicia sesión