Uncovering the British legacy in Andalucía

From building railways to bringing football and golf to the south of Spain, these are some of the marks left in the country by British immigrant workers in the 19th century

Louise Montefiore

Malaga

Friday, 23 August 2024, 15:02

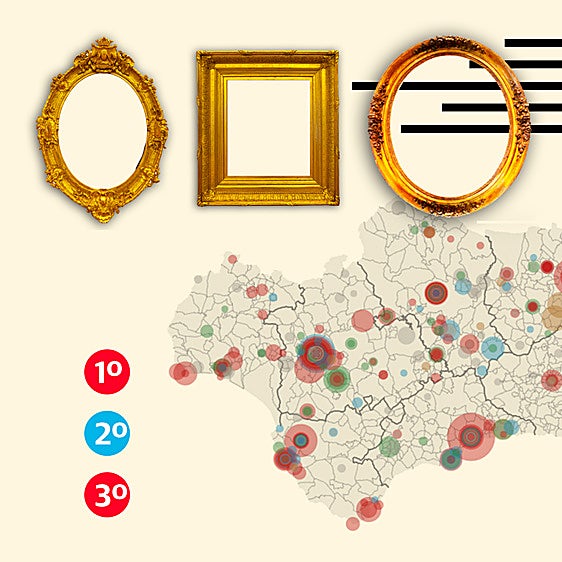

In the mid-19th century, British industrialists flocked to southern Spain, drawn in by the potential to exploit its land for minerals. Their presence has shaped Andalucía as we know it, leaving traces which are still visible to this day: this is how.

Seville

Seville is where it all started, with Lady Mary Herbert de Powis, who emigrated to Spain in 1727, setting the precedent for British mining activity in Andalucía. She soon struck a deal with the Compañia Española to drain and reopen the mine at Guadalcanal in Seville. By 1732, she had done so. Failing to uphold its side of the agreement, the Compañia Española did not pay Lady Mary for draining the mine, nor award her any of the profits it produced. Following a legal battle, she was awarded mining concessions at Guadalcanal. Lady Mary's story in Seville ends with her mining rights being rescinded when Ferdinand VI came to the throne. The rest of her life was dominated by debt, and she died in 1775, aged 89.

Guadalcanal fell briefly into the hands of Duncan Shaw when he set up the Guadalcanal Silver Mining Association in 1848. However, the venture failed and Shaw set his sights instead on Linares - but more on that later.

Aside from Guadalcanal, the Cerro del Hierro (literally 'Iron Hill') is where the most obvious marks of British mining in Seville can still be seen. In 1893, the mine here was taken over by William Baird and Company. Mining paused during the Civil War, before being taken over by a Spanish company.

Traces of British presence are still evident along the Vía Verde de la Sierra Norte hiking trail, which leads from the Cazalla-Constantina Station to the Cerro del Hierro, considered a 'Natural Monument'. The route goes past the mines and the site of the old English settlement, as well as parts of the old purpose-built railway track which linked the mine to Seville's port.

Huelva

Undoubtedly the most famous example of British influence in the south of Spain, the Rio Tinto Company Limited (RTC) was founded in 1873 by British industrialists when they took over the copper mines in Huelva from the Spanish government. Rio Tinto still exists as the world's second biggest mining corporation, and is currently at the heart of controversy in Serbia regarding a lithium mining project.

But this is not the first time there have been protests against Rio Tinto. In the late 19th century, there were strikes over unsafe mining practices, banned in the UK but profitable for the British company in Huelva. The industrial action on 4 February 1888 is considered to be the first environmental protest in Spain.

The success of the RTC in the Riotinto-Nerva mining basin has left an enduring legacy in Huelva. The Barrio de Bellavista is a neighbourhood located near the mines, erected by the RTC between 1883 and 1928 to house its workers. Built in Victorian style, it stands in striking contrast to traditional Andalusian architecture. A number of other signs of the century of British presence still remain in the neighbourhood: the tennis courts of the Club Inglés (English Club) where workers at the mines played, the Presbyterian Chapel, built in 1891, the Bellavista Protestant Cemetery and the Bellavista Golf Club, founded in 1916 by English miners, the first golf course on the entire peninsula. Also located in Bellavista is Casa 21. Dating back to 1885, this is a house that has preserved its Victorian-style furnishings and interior. Open to the public, across its three floors are photographs and objects which illustrate what life was like in Huelva for British workers and their families.

They are also the ones who, by holidaying there, contributed to turning Punta Umbría into the seaside tourist destination it is today. Evidence of this is the Casa de los Ingleses museum, a reconstruction of British holiday homes in Punta Umbría from the time.

To access the seaside, families travelled along the purpose-built Riotinto Railway, which connected the mine to the port of Huelva. Designed by George Barclay Bruce, the track was opened to passengers from 1895 to 1968, connecting different municipalities in the region. This made movement for residents of Huelva province more accessible.

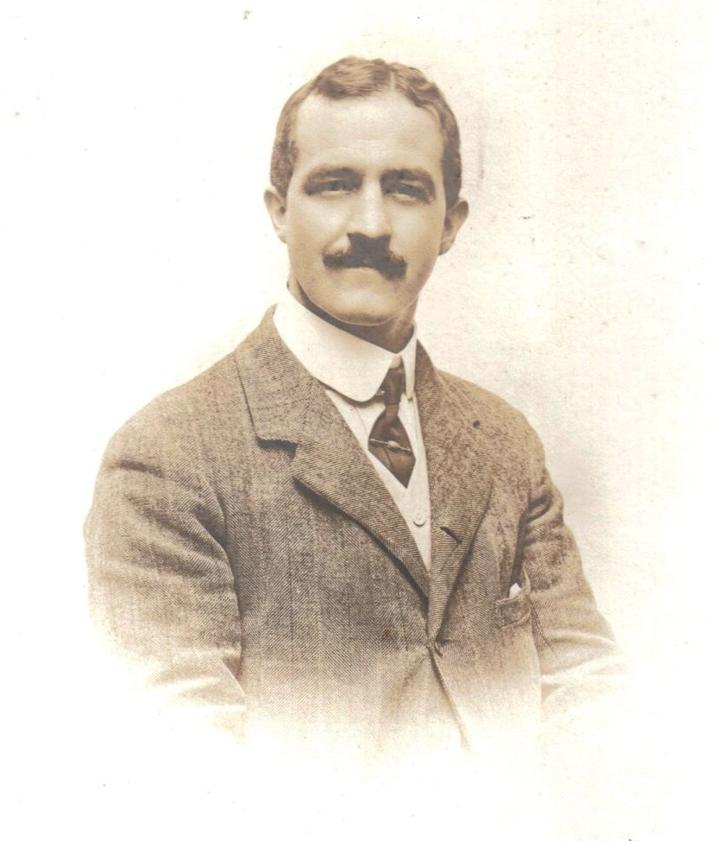

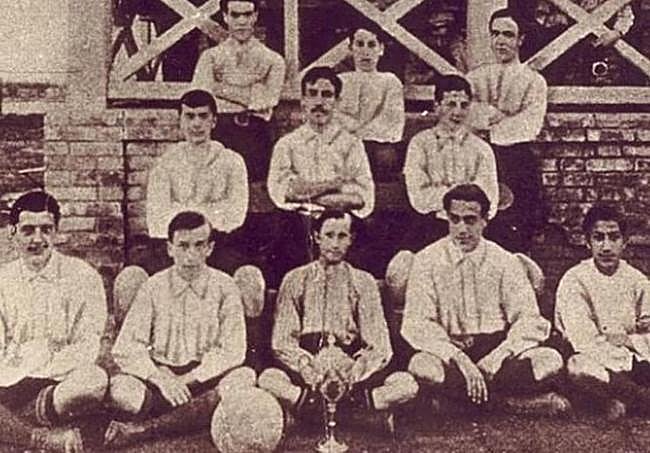

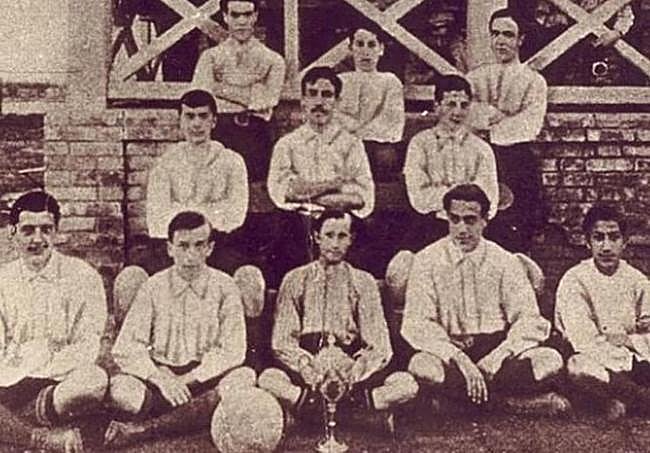

But the most well-known result of British presence in Huelva is its part in Spanish football history. Alexander Mackay and Robert Russell Ross founded the Huelva Recreation Club in 1889 for workers at Rio Tinto. Known today as the Recreativo de Huelva, it is Spain's oldest football club. The first official football match in Spain was played in 1890, under the rules of the English FA, between the Huelva Recreation Club and the Sevilla Football Club (now Sevilla Fútbol Club).

Zoom

The old mine can be visited at the Riotinto Mining Park, which includes a train ride along the restored 12 kilometres of Riotinto Railway track. On the first Sunday of the month between November and April, the carriage is pulled by an original steam train from 1875 - the oldest working steam engine in the country.

Jaén

Alongside Huelva, Linares was one of the most important areas for British mining. Though the Brits were not the first to recognise its potential - the Romans had exploited the land over 2,000 years before - in the 19th century, it was Duncan Shaw who was particularly influential in the area, after he relocated here following his failed project at Guadalcanal. By 1852, the Linares Lead Mining Company was in action. Thomas Sopwith was another important figure in Linares, working the La Tortilla mine from 1864. In the 19th century, Linares was one of the world's greatest lead producers: in 1896, the Linares-La Carolina area produced more lead than all of England.

Due to the unprecedented volume of English workers in Linares, the Linares English Cemetery was established in 1855. This was Andalucía's second Protestant cemetery and is still there, witness to the British presence in the area. Buried here is Reginald Bonham-Carter, the great-uncle of the actress Helena. Reginald was an engineer in Linares who worked with the Sopwiths before taking up the lease of the Abundancia mine. This is where he died in a mining accident in 1906. Known locally as Don Regino, this name is inscribed on his grave underneath his real one.

British mining endeavours in Linares had a huge economic impact on the region. The technology introduced, Cornish technology in particular, was adopted by Spanish mining companies, and railway lines were built linking the mines to other cities. The town of Linares grew a great deal during the period as a result.

As in Seville, hiking trails are the key to discovering the traces of British influence in Jaén. The route from the town of Linares to the Minas de Los Lores, owned by Thomas Sopwith, is a good option. Linares also has a museum and visitor centre in the old Estación de Madrid which explores its mining legacy.

Other traces of British legacy

British mining efforts were present across virtually all of Andalucia. The Scottish-based Marbella Iron Ore Company was formed in 1871. Parts of the railway that connected the mines to Marbella's port are still visible.

In Almeria, the impact of the British mining legacy is clear in the name of the Cable Inglés (English Pier), a loading bay in the heart of the city built to accommodate trains transporting iron from the once British-run Alquife mine in Granada, which is currently the largest open-cast iron ore mine in Europe. After years of inactivity, the Cable Inglés opened last year as a pedestrian walkway and viewpoint, overlooking the bay of Almeria.