Robert Mosher: the most exclusive Costa del Sol architect whose work is in danger of extinction

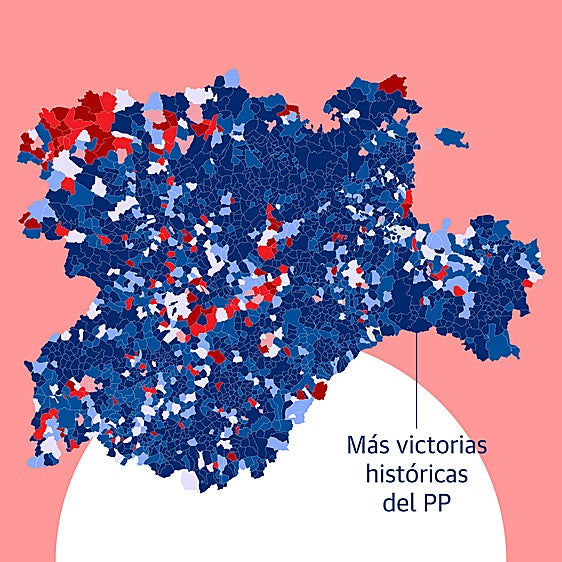

Lloyd Wright’s disciple arrived in Spain with the Marshall Plan, fell in love with Marbella and left an urban planning legacy that is as unknown as it is unprotected

She met him through photographer Pepe Marpy, an indispensable figure in Marbella’s nightlife: “I’m going to take you to a place you’ll really like,” said the photographer to architect Elisa Cepedano Beteta, and she followed him with her eyes closed.

She knew he was not going to disappoint. What she never imagined was that the encounter would mark her professionally and personally.

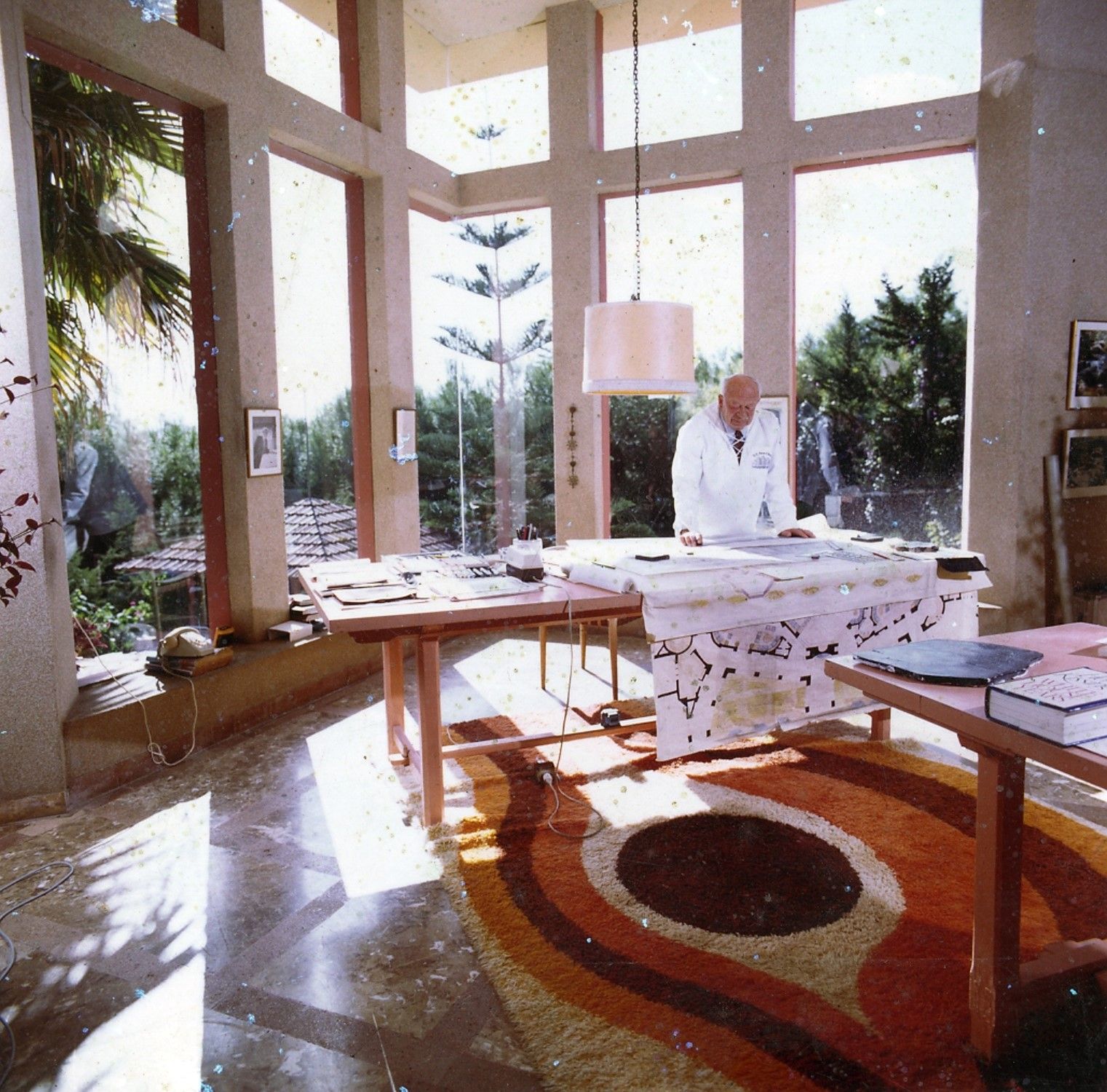

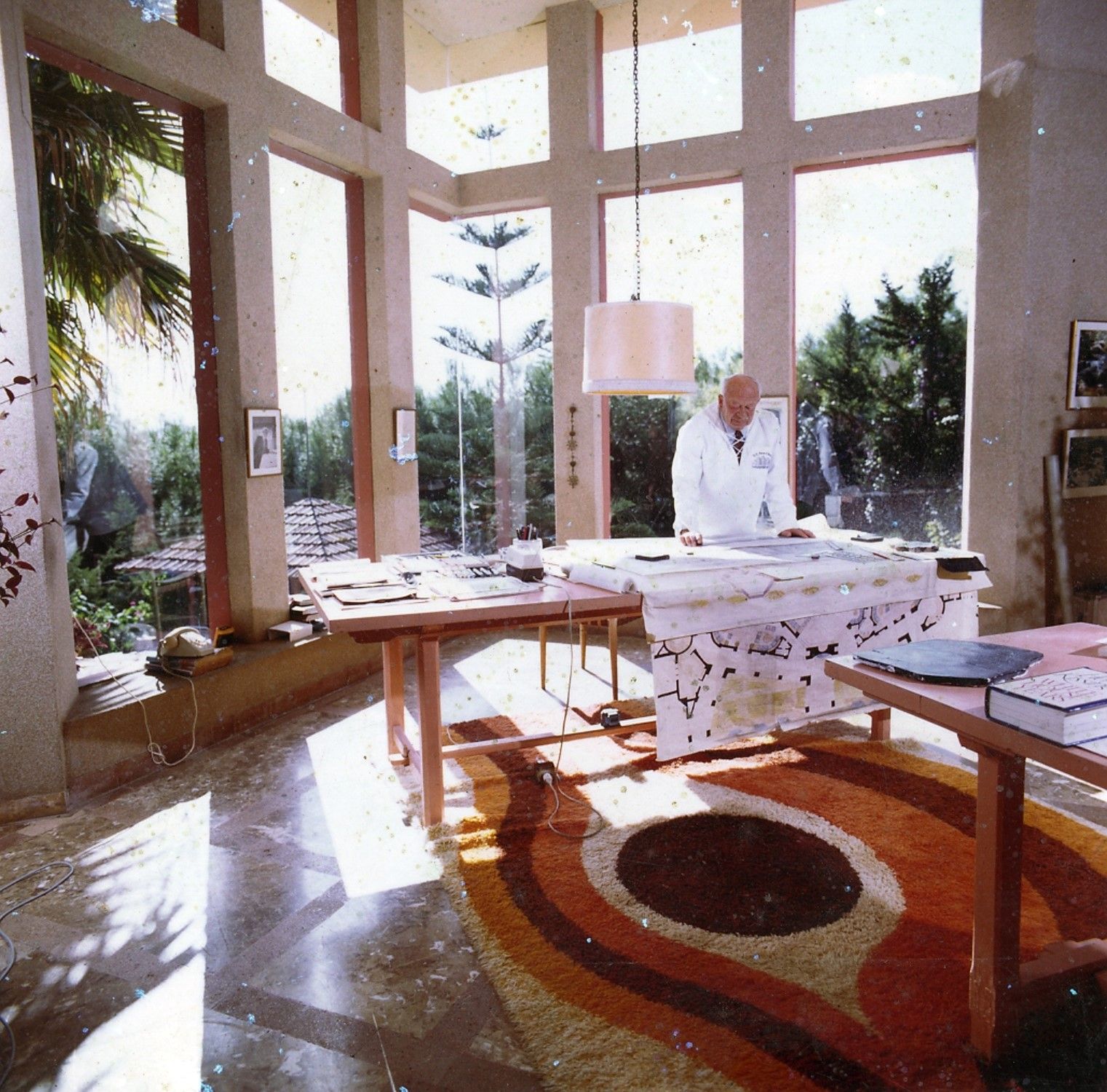

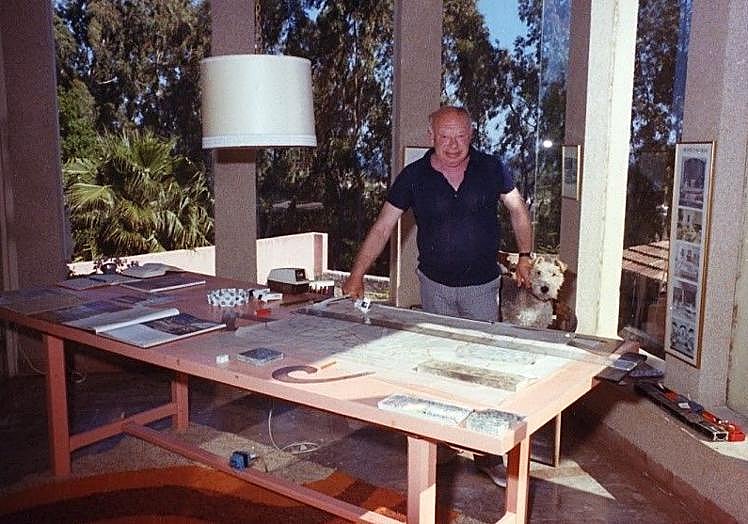

The destination was a villa in Nagüeles with a welcoming name: El Remanso (The Refuge). But before meeting the owner who lived up to that title, she recognised the drawing of Frank L. Wright’s legendary Fallingwater house on the stairs.

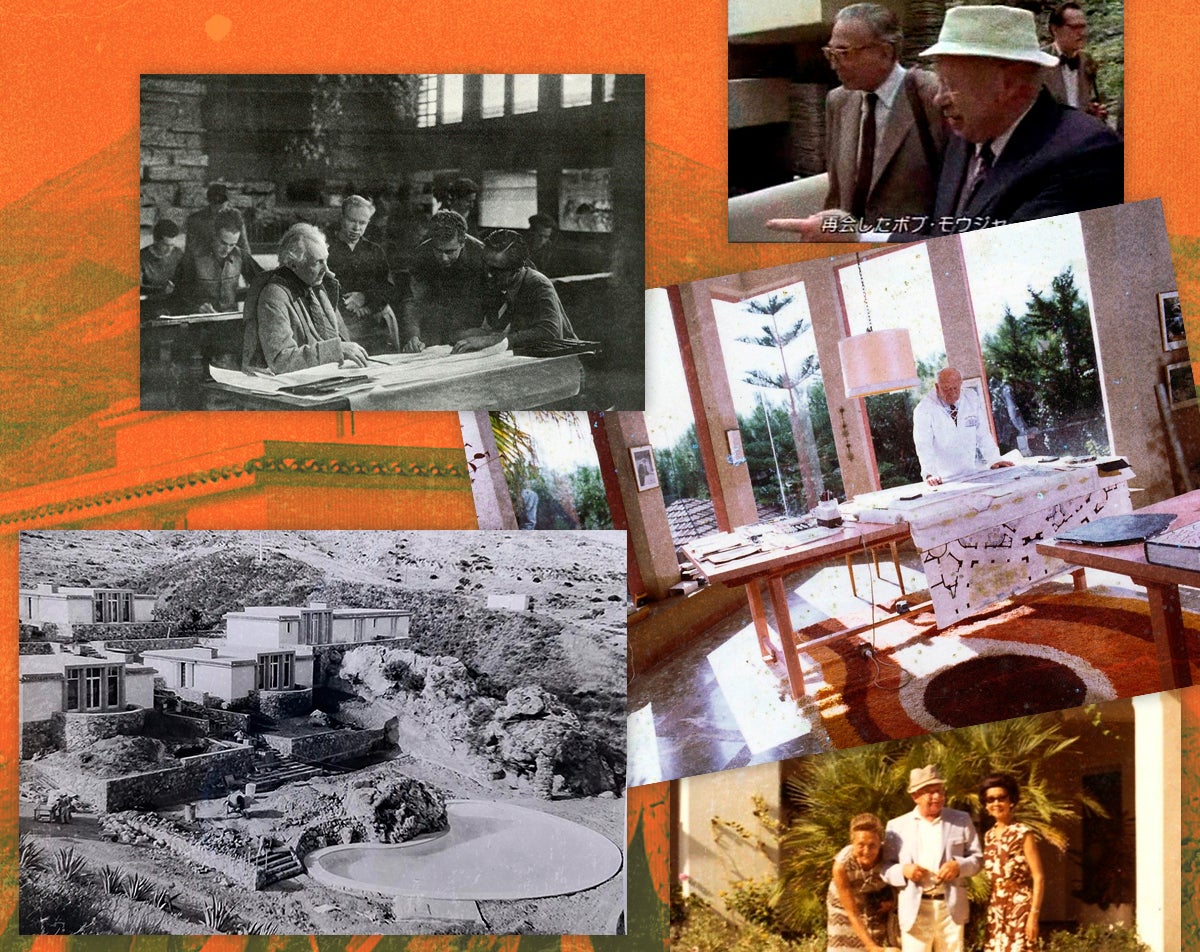

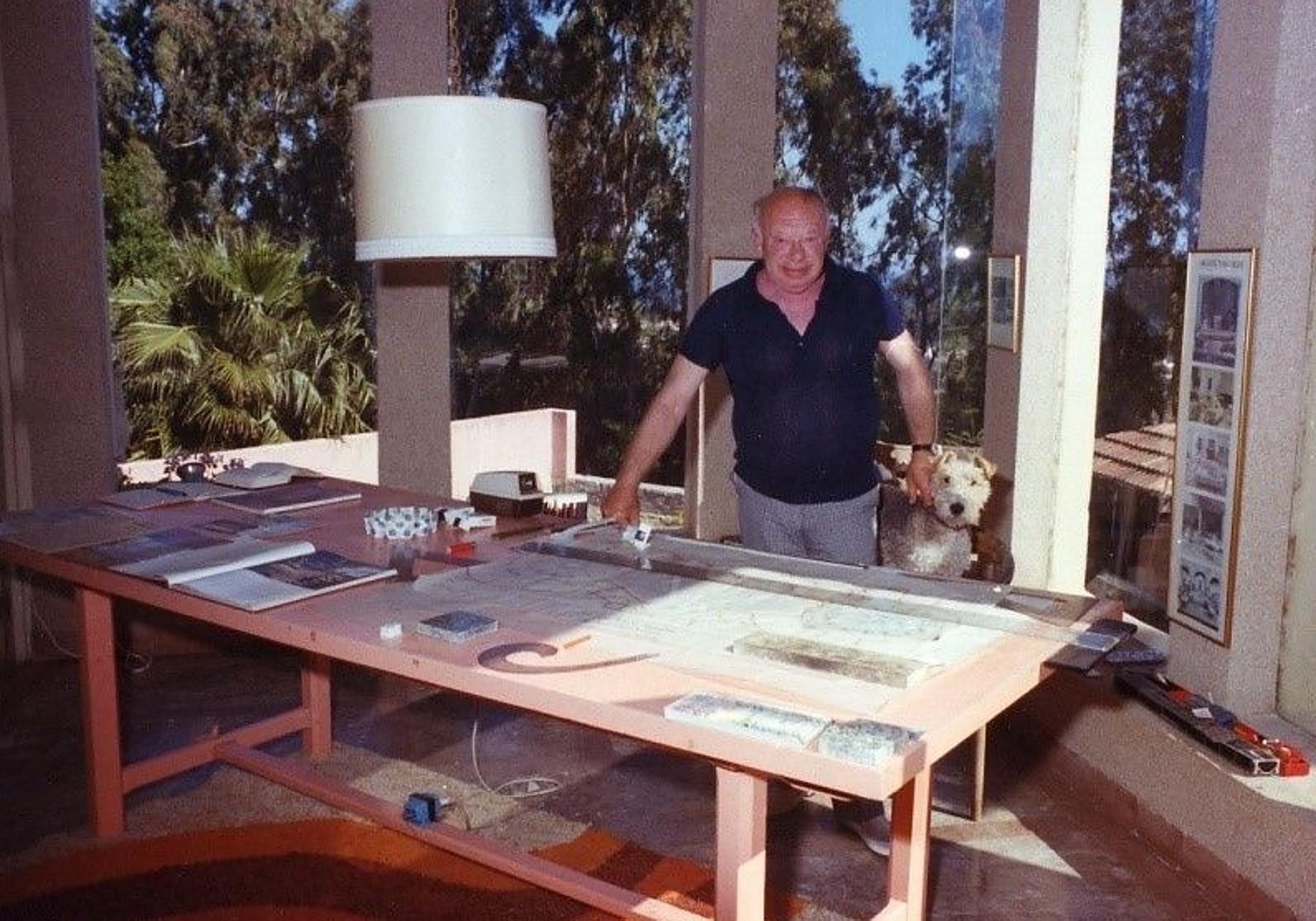

“But it wasn’t a reproduction, it was the original sketch,” says the then visitor, who was about to meet Robert Mosher, a smiling, big, friendly guy, framed by large vertical windows that amplified the staging of that introduction.

It was then that she realised she was in the presence of Lloyd Wright’s right-hand man and the true author of the sketch of the most famous residence in the history of architecture. A man who, when he first arrived on the Costa del Sol, knew that he had found his own Fallingwater.

He lived here from the 1950s until his death in 1992 and left here his most important work, an architectural encounter between organic style and the Andalusian spirit. A legacy that is unprotected and is being lost.

-U26456772012rkP-650x455@Diario%20Sur.jpg)

Zoom

-U26456772012rkP-650x455@Diario%20Sur.jpg)

“One day he would be creating a house for Baroness Von Pantz - the largest shareholder of the multinational Avon - and the next he would be bidding for a small contract because he was passionate about design. He didn’t need to, but he entered. I was always struck by his lack of ego,” recalls Cepedano who, together with her partner Roberto Barrios, ended up becoming a regular visitor to the American’s house and the main expert on his work.

She explains how he came to Spain with the arrival of the American bases in the 1950s and the Marshall Plan which, although it passed fleetingly through this country, also opened up the lock of the dictatorship to the world. A Spanish-American collaboration that, in the Trump era, seems a long time ago.

Zoom

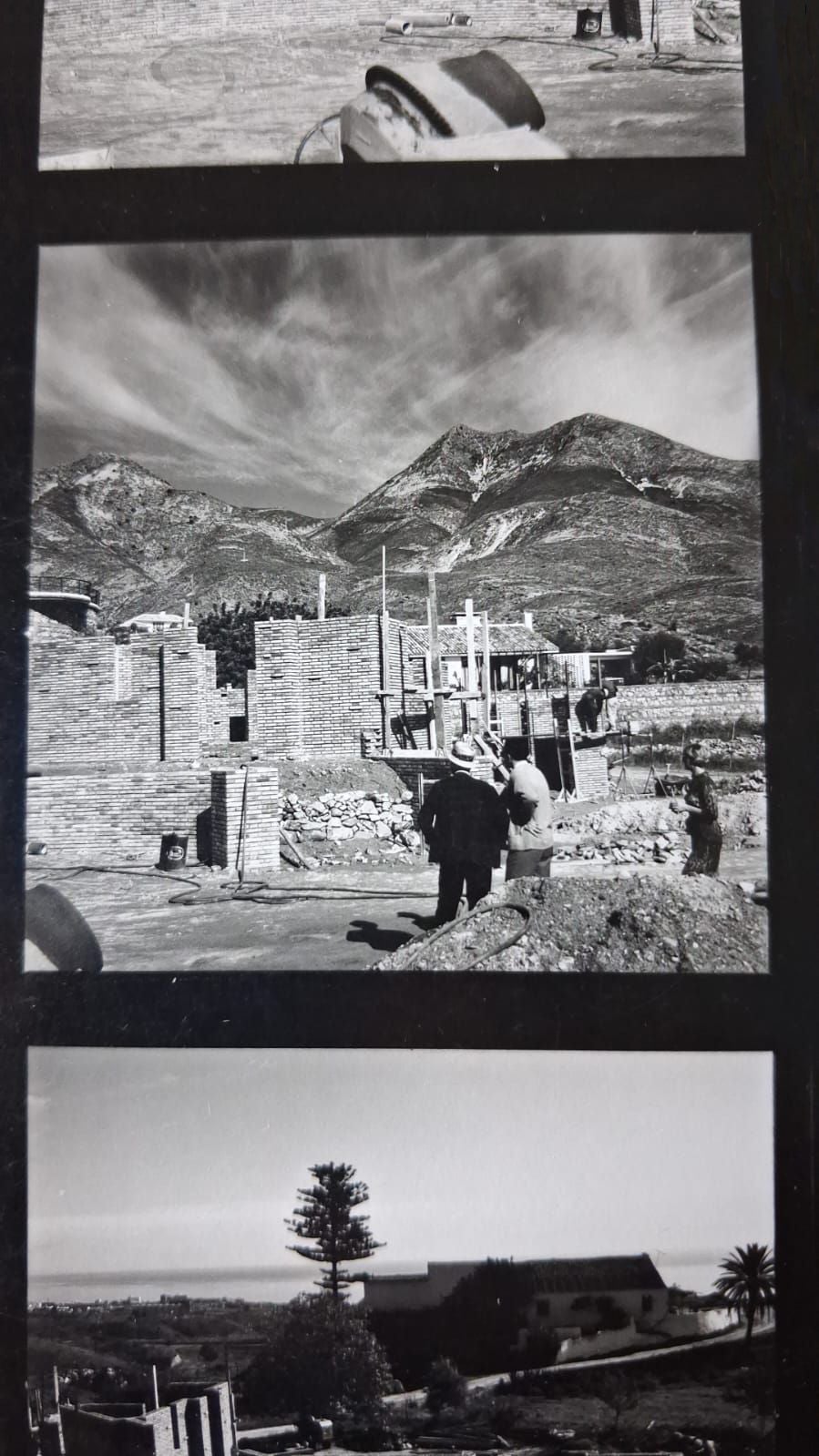

However, Robert Mosher did not come directly to Spain. As the researcher and journalist Carlos Zamarriego recalls, after spending the 1930s in Frank Lloyd Wright’s studio as one of his closest colleagues, he went his own way in the 1940s and headed for Europe.

He passed through Germany, made a stop in Italy and finally arrived in Madrid. “He had a very good relationship with the diplomats and his first commission was the Casa Lange, in El Limonar,” recalls Elisa Cepedano, who, in her study, Robert Mosher, Mirada Abierta y Sueño de Viajar, dates this cult project of Malaga architecture in 1957.

The developer was American Colonel Roy Allert Lange, who gave him carte blanche. Here the urban planner laid the foundations of his style by mixing organic concepts with the Mediterranean spirit and local materials, also taking care of the environment and the incorporation of nature into the living space.

A house "facing the south perched on a small promontory like a smile to the Mediterranean", was how the US embassador described the house that Mosher created in Marbella

“When he came to Malaga he fell in love,” reveals the architect, who adds that Mosher made the Costa del Sol his natural area of influence and, particularly, Marbella where he built his home.

He never married and was never known to have any descendants, but he left a recognisable legacy in the form of residences and villas.

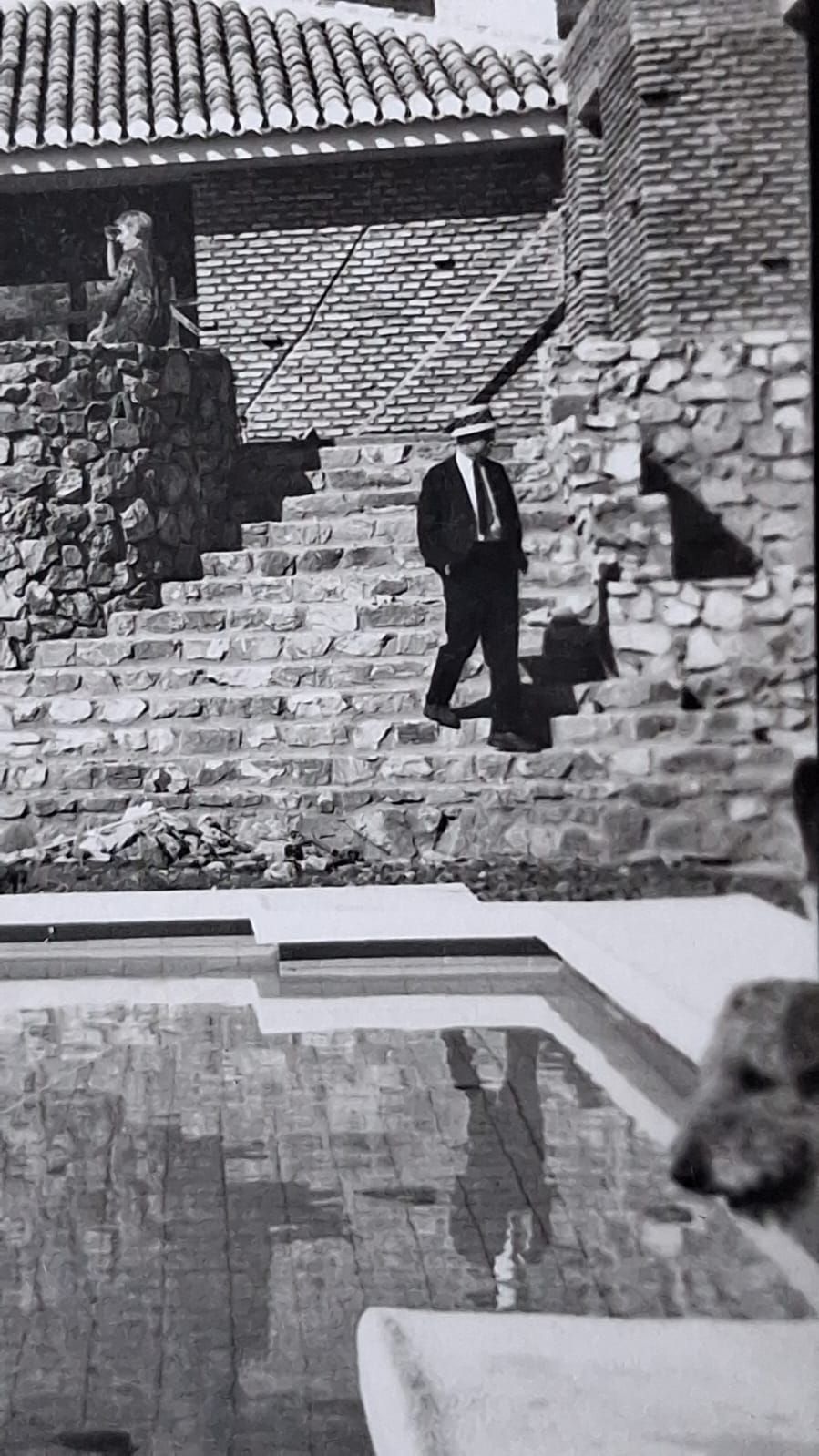

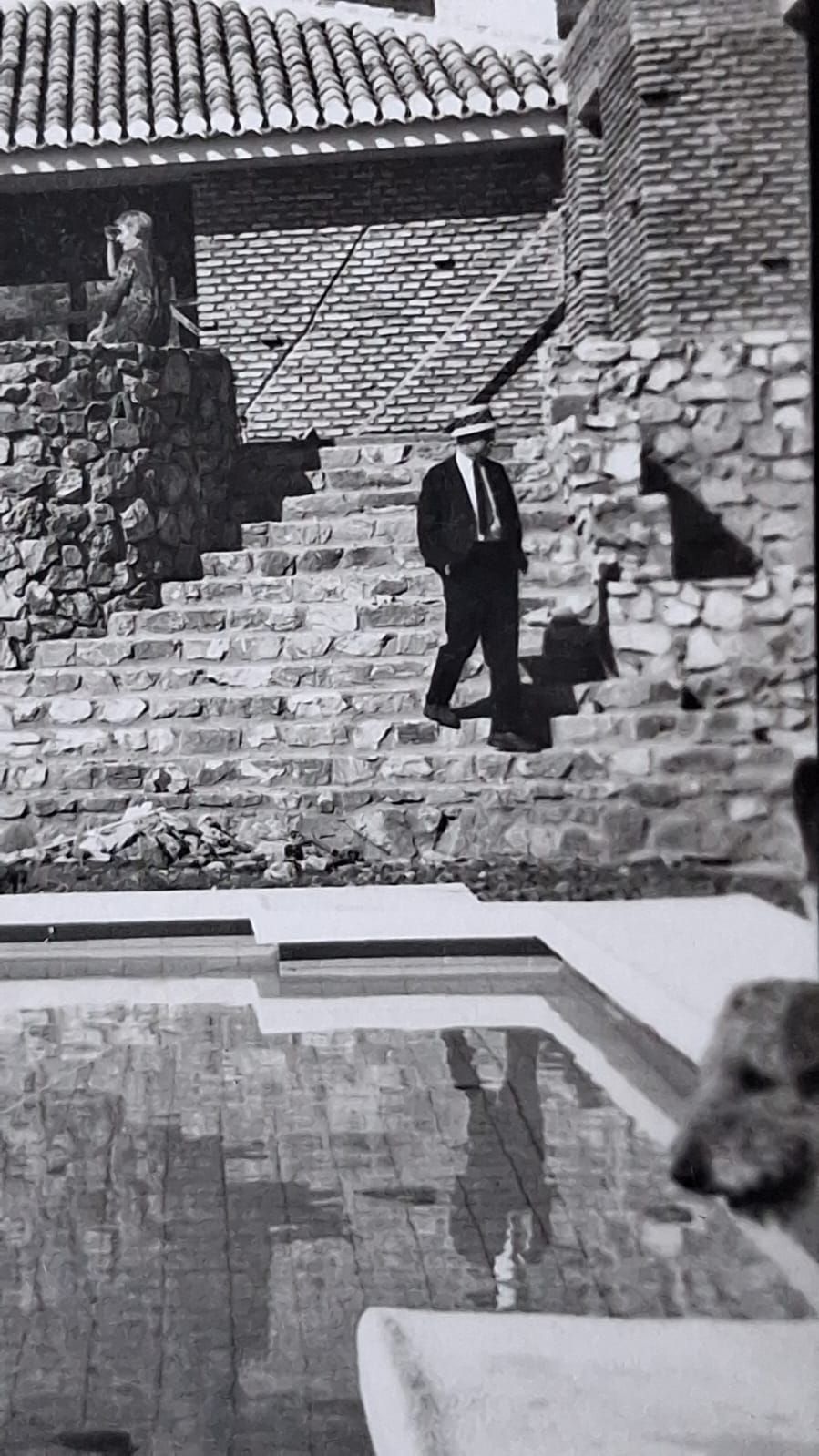

Among them is the home of John David Lodge, the first US ambassador in Madrid since the UN lifted its veto on Spain in 1955, who called on Mosher to build his holiday home in Marbella on the Santa Petronila estate.

Zoom

Zoom

That commission was an architect’s dream: the bill was not a problem and he had at his disposal 8,000 square metres stretching down to the beach, bordering the properties of the Duke of Alba, Petronila Escandón y Salamanca and the Marquis of Villalobar. A villa “facing south on a small promontory like a smile at the Mediterranean”, wrote the owner. “The clients themselves are the ones who best define Mosher’s architecture,” Cepedano says.

A ranch on the Costa del Sol

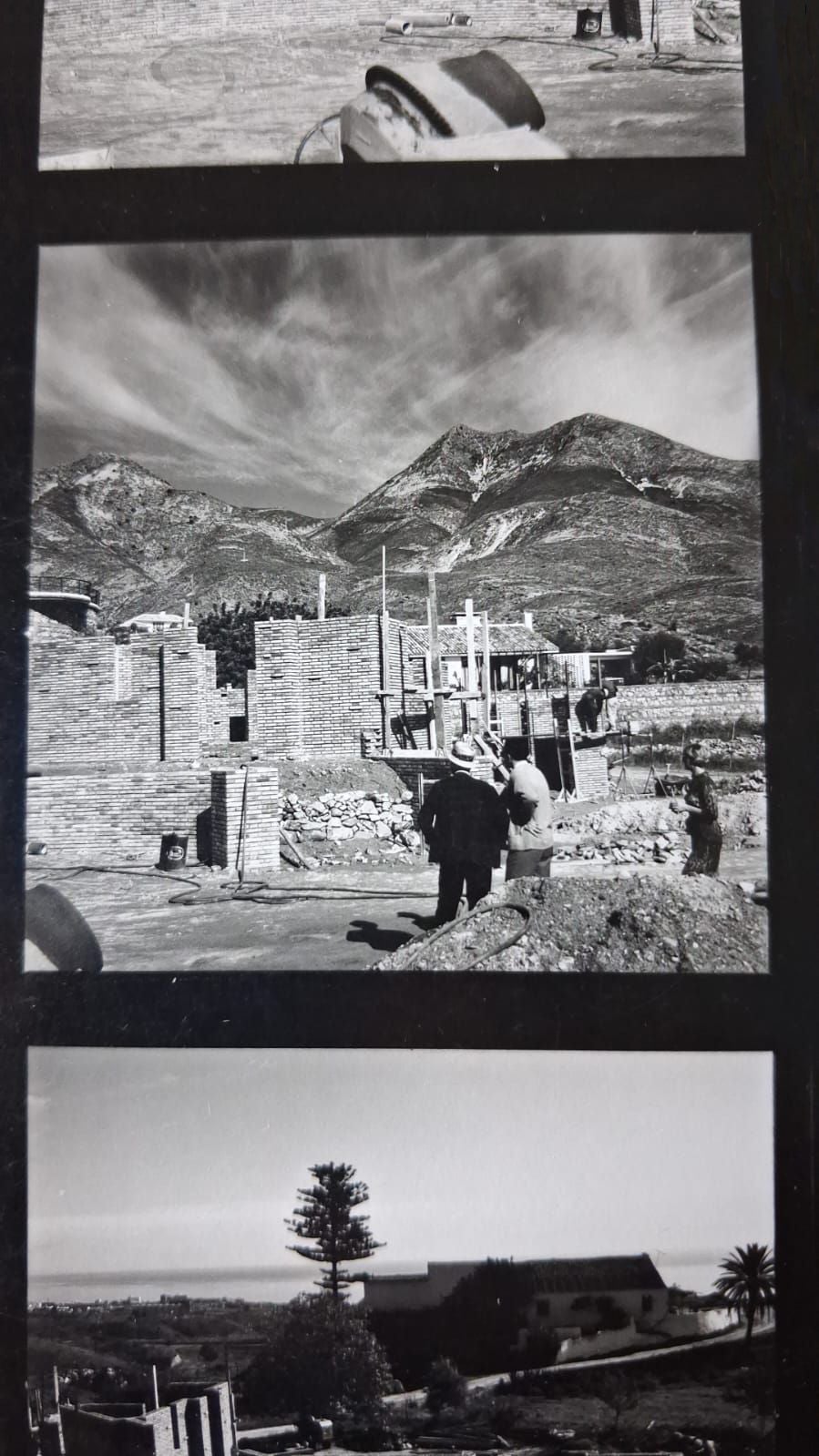

Mosher’s heart was in Marbella, but his most iconic and extensive work is in Benalmádena.

“His meeting with the brothers Simon and Maurice Beriro was crucial, as they commissioned him to build Rancho Domingo,” explains Carlos Zamarriego, who is preparing a book on this emblematic development on the Costa del Sol.

It is not known how the developers and owners of the Hotel Tropicana and the architect met, although the researcher points out that the businessmen were of Sephardic origin from Casablanca (when Morocco was a Spanish protectorate), while the American was also Jewish. What is certain is that the understanding was total.

Zoom

Zoom

Robert Mosher converted a field of olive trees and cattle into a luxury residential complex. The estate is made up of 27 villas, most of them designed by the American, such as the emblematic La Rotonda, where Simón Beriro himself lived - today it can be rented for 2,300 euros a day in high season.

There was also San Ysidro, which belonged to producer George Ornstein who brought the first Hollywood productions to Spain, or Arcadia, where Alain Delon stayed during the filming of Lost Command.

The estate, along with Pueblo Rancho Domingo (made up of 12 apartments) or La Roca residence, shows the “prodigious” architecture of Lloyd Wright’s disciple, as Cepedano Beteta explains.

Of the 60 villas he is estimated to have built, Casa Lange in El Limonar, the architect's first house in Spain, is the only one listed by the Junta de Andalucía, while Rancho Domingo in Benalmádena has municipal protection

“Instead of transforming the orography into a slope, his designs adapt to the terrain,” says the architect, who also emphasises the large windows and the adoption of the Andalusian building style of the white villages. However, their pronounced overhangs were often altered by the project managers.

“On occasions, they neutered his designs,” explains Cepedano, whose urban planning study on Rancho Domingo was used by Benalmádena town hall as the basis for protecting this complex. The expert brings to the table one of the problems that the American encountered, as, despite building villas over more than three decades, he never signed a plan himself.

He was not a member of a professional association, so his projects were legalised through a Spanish colleague and he was unable to direct the building work,” says the architect.

Zoom

Zoom

Probably, this “lack of ego” that Cepedano Beteta speaks of meant that the architect did not claim his prominence in the official paperwork.

“He was a loving person who didn’t need anything,” says the researcher who insists on his humanity, while explaining that Mosher had the complicity of his clients who were also friends.

Today, however, his work is falling into oblivion and, most seriously, many of the properties are uncatalogued or undiscovered. Such as the Marbella residence of Baroness Terry Von Pantz for whom he built a beachside ‘bungalow’ with twelve guest rooms, quarters for nine servants and a dining room for a hundred guests.

However, the most serious threat to this unique legacy of the province of Malaga is its lack of protection. Except for the aforementioned Rancho Domingo, which is under municipal conservation, the Lange House in Malaga city is the only one listed in the Andalusian regional government’s general catalogue of historical heritage.

“There is no census of his work, but he built more than 60 houses,“ says the architect and leading expert on the work of her American colleague, who warns about the future of this urban heritage which, in some cases, has already been bulldozed.

“If it is not protected, it will continue to disappear.”

Zoom

The last plot in Rancho Domingo will revive the Casa de la Cascada

Félix Martínez makes no secret of the fact that he is in love with Rancho Domingo and the concept that American architect Robert Mosher applied to this privileged corner of Benalmádena overlooking the sea.

He maintains that this is “the cradle of organic architecture in Spain” and, for this reason, he has put a lot of effort into acquiring the last free plot of this estate, which still belonged to the Beriro family who promoted this “architectural jewel” of the Costa del Sol.

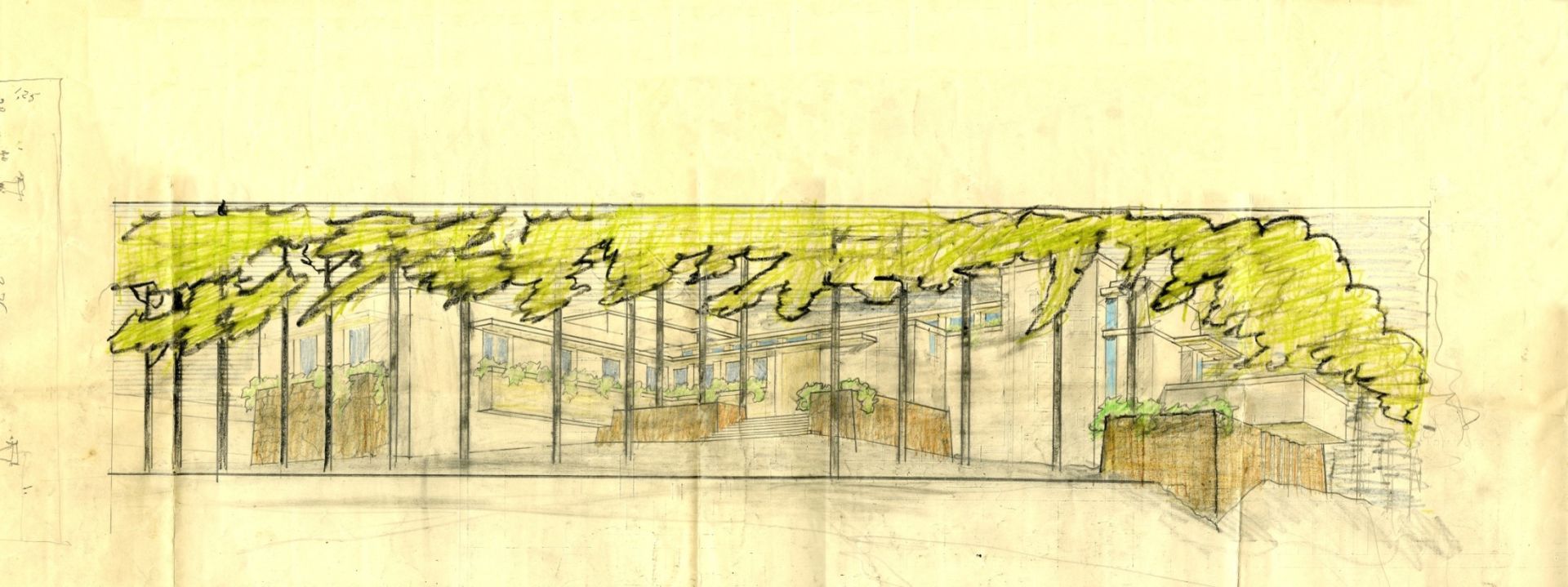

The project he has put on the table is a development of 43 homes that updates and adapts the iconic Fallingwater. “We want to maintain its essence,” explains Martínez, CEO of hubLIVING, which has already launched this initiative under a brand name that says it all: Mosher Collection.

“Our aim to to respect the surroundings and get closer to his architecture,” says the head of the Benalmádena-based real estate firm, whose aim was to organise an international contest for the design of the development, until the architect César Frías - who designed the 30-story skyscrapers in Malaga’s Martiricos district or the Distrikt building in Lisbon - learned of their intentions and came up with plans that encompass his legacy. It was an offer they could not refuse.

“We don’t want to do the same as Wright and Mosher did, but we want to reinterpret Fallingwater,” says Martínez.The development will be built on a crag, so the construction solution will be to apply the philosophy of organic architecture.

“We don’t want to fight against the mountain, and so the complex will be tiered and will be supported by it,” explains the developer who adds that there will also be a “Caminito del Rey-style” walkway, a co-working area, restaurant and outdoor infinity pool.

Credits

-

Formato Alba Martín Campos

¿Tienes una suscripción? Inicia sesión