Restoration job reveals the secret history of this work of art from Malaga museum

Its transfer to Madrid for an exhibition at the Prado Museum uncovers a new date and an unconventional enlargement

The scene depicts a tender moment. A row of mothers with some of their children already undressed wait in line for the doctor to inoculate their infants. The first in line, elegantly dressed and with her son ready for the jab, sits apart from the rest; their clothing is simpler, a more everyday wardrobe. The differences in their social class did not escape the keen gaze of Vicente Borrás Abella from Valencia when he painted La Vacuna (The Vaccine), a delightful work from the Prado that was kept at the Museum of Malaga, reflecting the popularisation of healthcare in Spain at the beginning of the 20th century. It was for this very reason - the chronicling of an era - that the argument was made for it to be included in the exhibition Arte y transformaciones sociales en España (1885-1910) (Art and Social Change in Spain) , which is on display at the Madrid museum until September. Since the work was already travelling to the museum of museums, the restoration department there took the opportunity to give the piece the once-over. Therein lay some big surprises.

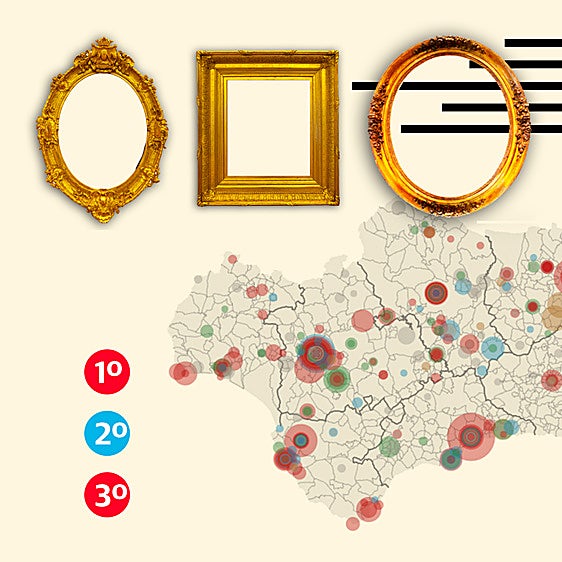

In principle, the idea behind the cleaning of the painting involved a re-touch of the colours in The Vaccine, but the painting came with added extras. "Although it is from our collection, the work was never physically in the Prado, so when it arrived here we saw that the canvas had an addition that was not a piece of canvas, but a pine board, which is highly unusual and something we had never seen before," said Lucía Martínez Valverde, painting restorer at the Museo Nacional del Prado. She simply could not believe this painting had been extended using two such different materials

The added area

The extension, about 10cm high running full width of the canvas, shows part of the table and a cowbell used to rinse needles.

Signature

Perhaps the most important thing: the artist’s signature...

Full name signed

"Borrás Abella", whose writing matches the painter's signature in later years (after 1905).

The back of the painting

But that is not the only secret uncovered by the restoration - there were more finds on the back.

This addition was fixed to the frame from behind using two metal clips and a nail in the central part, while the join between board and canvas was covered from the front with filler. Once again Martínez stressed that this was an extremely unusual method for adding to a contemporary painting. Normally any additions to canvas are done using the same material, extending the frame and then sewing both pieces of canvas together. This is not the case here, which then opened up new questions and puzzles for the specialists to solve. Firstly, when was that addition made? Then, were both parts painted at the same time or was the part on the board painted at a later date? And why this expansion of the work anyway?

An episode of CSI

To address all the questions the team of experts had to carry out a forensic-like investigation. While no crime had been committed, the painting had to give up the evidence, much as a body would in an episode of CSI. "To analyse the join in the painting where both areas met, we carried out an X-ray fluorescence analysis (XRF), which determined the chemical composition of the materials used and which ruled that the painting that is on the wood and on the canvas were done practically at the same time or within a very short window of time," said the restorer. She added that those ten centimetres gained by the painting allowed it to reach one metre in height. That extension covers the entire width of the work. However, from an artistic point of view, it does not contribute that much more to the scene. All that the artist has added in those 10cm is an extension of the doctor's work table and a clearer image of the cowbell used by the doctor to sterilise his needles while vaccinating, probably against smallpox. The most important thing about this extra bit lies in the presence of Borrás Abella's signature there, revealing new information to the restorer.

The X-ray fluorescence analysis showed that the painting on canvas and the additional painting on wood were done at the same time or within a very short window of time

"It is a different signature from [his] other paintings since the handwriting is looser and more mature, so it is different from the rest of his work," said Lucía Martínez. She added that another of the unknowns was the exact date of its execution, since until now it had been dated between 1890 and 1900. "We do not know when it was painted, but it corresponds to the artist's style and his signature from 1905," said Martínez. Added to the unknowns was the lack of knowledge of the moment in which this painting came to the collection in Malaga. The answer to that was found on the back of the work.

The join to expand the picture by 10cm

A wooden board is attached to the canvas with a frame over the top, a very extraordinary method, making the work one metre high.

Dimensions

"151x90" appears twice on the back, the original dimensions of the canvas before being expanded by 10 cm to reach a metre high.

"Borrás"

The artist’s last name appears in chalk writing on the back, although the two previous capital letters (apparently "D S") cannot be deciphered.

Inventory at the Prado Museum

The inscription "Nº 7557" in red, along with some header/footer code, refers to the inventory number of the painting within the Prado Museum’s collection

The artist's brother

Behind the numbers in red you can just make out in pencil the words “Property of Gabriel Borrás”, brother of the painter and a restorer himself at the Museum of Modern Art.

Inventory at the Museum of Modern Art

The inscription "Inª 73" corresponds to the stock-take that was done in 1954 at the Museum of Modern Art, to whose collection this work belonged before going to the Prado.

"On the back we find the handwritten name of 'Gabriel Borrás', who is the painter's brother," said Martínez. It would appear that this relative was the owner of the painting around the same time that he worked as a restorer at Madrid's Museum of Modern Art. The experts believe that this restorer left it in the art gallery since there is no documentation to prove the purchase of the work by the museum. A bit more digging in documents and archives provided the missing pieces to this story. It turns out that in 1911 the artist Vicente Borrás applied for the position of teacher of colour at the School of Fine Arts of Barcelona and presented them with this canvas/board to show off his skills. The Valencian artist won the position with a composition entitled Vaccination of Children, a work that, according to photographs published at the time, matches the piece owned by the Prado.

A later work

As a result of this restoration and research "we have finally established 1911 as the date of the painting, since it was the year in which it was presented publicly," stated Martínez. The work has now been definitively catalogued with the title La Vacuna (The Vaccine), pretty much the original name with which the author presented it when going for the position of teacher of colour in Barcelona, a speciality in which the modernist painter was a master.

All of this leads us back to the beginning, when members of the Prado's restoration department were taken aback upon turning the painting over to contemplate that unprecedented extension of the canvas with the addition of a strip of pine. There is no single, correct answer here, although there is a very plausible one. This is Martínez's supposition: "Perhaps Borrás could have mistakenly noted the measurements of the professorial contest and, when he realised this, he decided to enlarge it to be able still to present it." She believes the painter used what he had to hand in the studio and added that piece of board so that the 90cm-high painting became one metre.

On the other hand, according to this restorer for the Prado, it should not be ruled out that the artist simply decided that he needed more canvas while he was painting and enlarged it for purely pictorial reasons. We are reminded again that the scientific and forensic evidence indicate that both parts were completed at the same time or thereabouts. Although imperceptible to the untrained eye when viewing the painting, over time that join has become more marked. For that reason Lucía Martínez's restoration work has consisted of a "bringing together" of that point of union between the different supports that fixed them together as the join showed signs of "some weakness".

Lastly, to honour its author, the work has had all its original colours cleaned and restored as part of its 'repatriation' to the Prado for this temporary exhibition on social change in Spanish society.

"You just have to look at the red of the headdress or the mastery and subtleties of the whites that Borrás achieves," she said. She is satisfied that they have achieved a balance with the piece's restoration without the need for further intervention. "At least for the next 200 years we shouldn't touch it."

Encarni Hinojosa

¿Tienes una suscripción? Inicia sesión