Malaga, a Second World War weapons testing ground

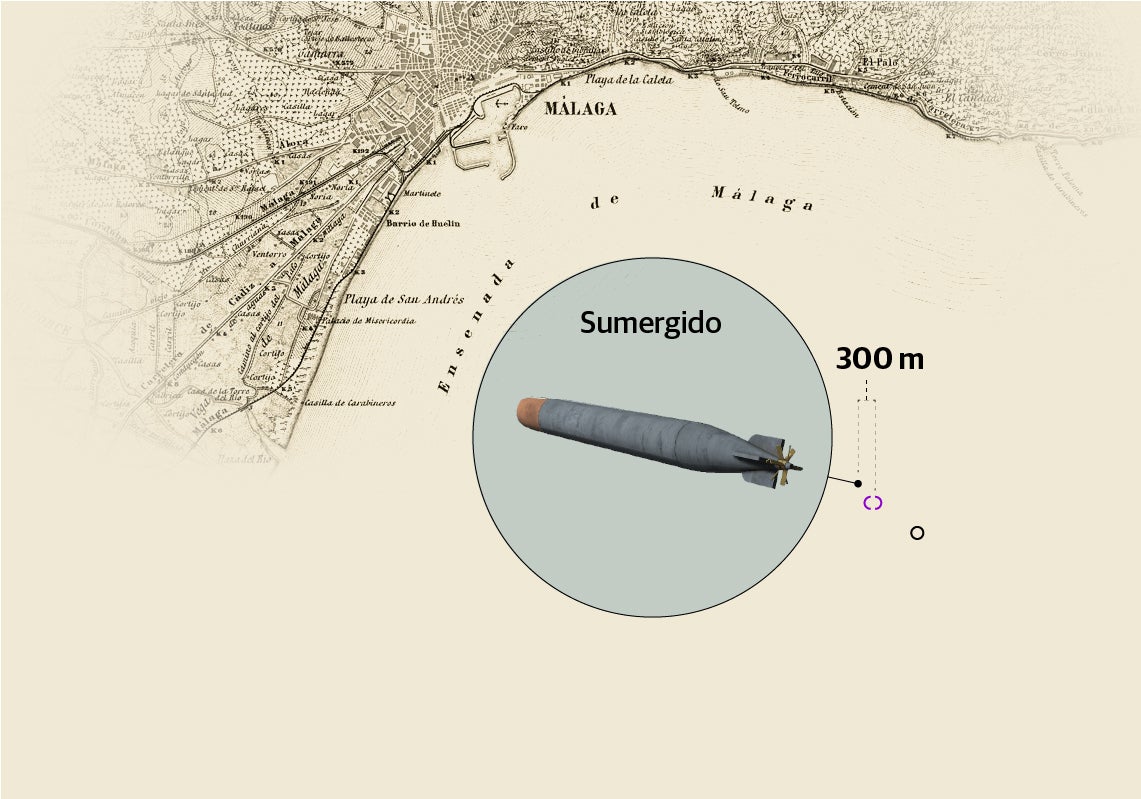

A Nazi torpedo that hit a C-3 submarine reveals all: authorities are studying how to disarm the weapon located by researchers in Malaga bay after its original discovery by an archaeological survey back in 2009

Francisco Griñán

Malaga

Friday, 5 January 2024, 18:02

The torpedo is set to blow up nearly 87 years too late. All theories as to the sinking of the Republican army's C-3 submarine were thrown out except for the true one. The truth became known in November last year when it was announced that a research team had located the Nazi missile that sank the C-3 sub. It was already known that a German U-boat (U-34) had attacked the submarine, but material evidence was lacking. News of its discovery also revealed that the torpedo was still intact. Yes, very degraded and corroded from almost nine decades at the bottom of the sea, but an unexploded bomb.

This confirms the hypothesis that the missile had passed through the hull of the sub without exploding. Although the torpedo had struck the submarine, the vessel quickly sank thanks to secondary explosions from air tanks and the weapons already onboard. As such, only three crew members were saved. The rest of the crew had no time to evacuate and they remain at sea, 70 metres down.

As one chapter closes on the sinking, others open on what else to do within these waters. Perhaps the most pressing matter is how to recover and defuse the torpedo. There is also a rewriting of the history books, as this discovery confirms that Hitler did attack a Spanish vessel without officially declaring war on the Republicans.

The official position, as stated to SUR by the Spanish government's provincial office in Malaga, is that it has handed over responsibility for the Nazi torpedo to the competent authorities, namely the Guardia Civil (responsible for coastal security), and the navy, (owner of the shipwrecked submarine). Both are currently considering the best way to disarm the missile. Back in the 1930s this was a state-of-the-art weapon.

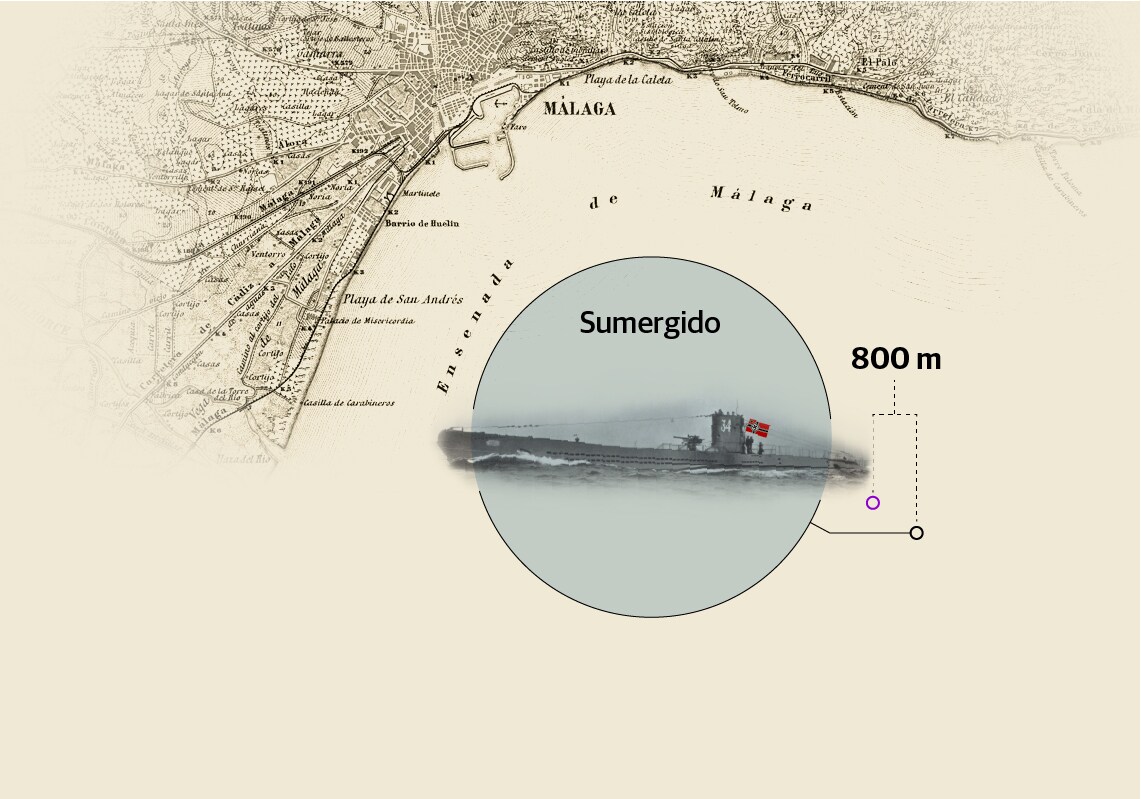

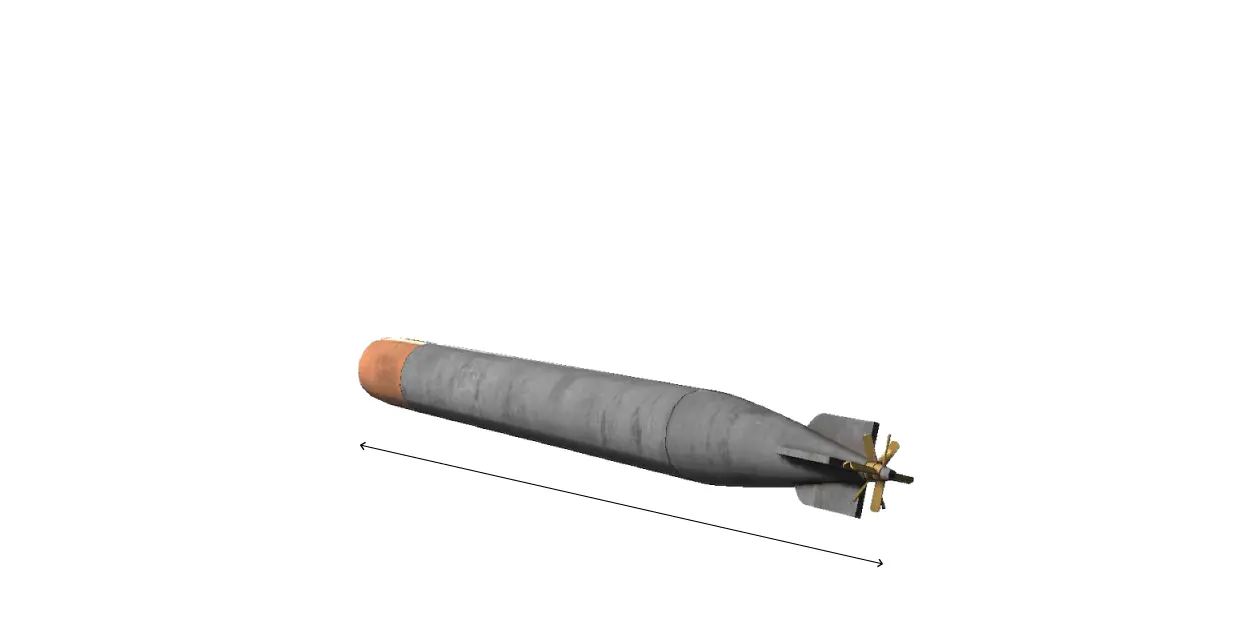

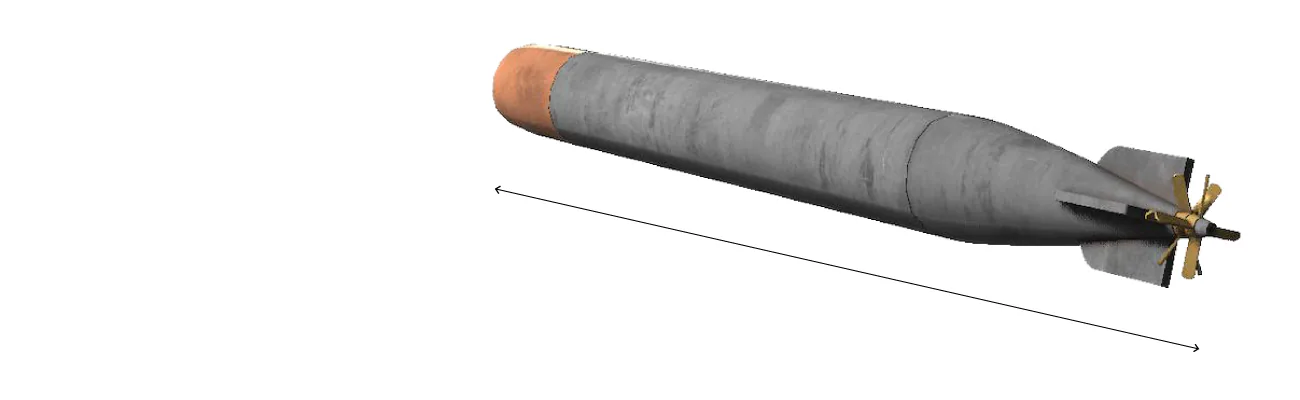

The tip of the G7 model would be packed with 280 kilos of a German-invented explosive more powerful than TNT. Weighing 1,750 kilos and fired 800 metres away from its target at a speed of 30 knots, the ballistic device had enough force to pass through any vessel, as happened in this case. The surprising fact is that it did not explode.

Engineer and merchant navy man José Luis Martín, who pinpointed the torpedo's location together with José Antonio Hergueta (filmmaker and director of the documentary about the C-3 Submarine 'Operación Úrsula'), has the answer. Being a new weapon at the time, German U-boats "were testing" their effectiveness and the German Reich's support for Franco gave them the opportunity to run trials on real-life targets.

Torpedo G7

Weight: 1,750 kg.

Speed: 30 Knots

Explosive charge: 280 kg.

Location: Depth of 66 m

Length: 7 m.

Torpedo G7

Weight: 1,750 kg.

Speed: 30 Knots

Explosive charge: 280 kg.

Location: Depth of 66m

Length: 7 m.

Torpedo G7

Weight: 1,750 kg.

Speed: 30 Knots

Explosive charge: 280 kg.

Location: Depth of 66m

Length: 7 m.

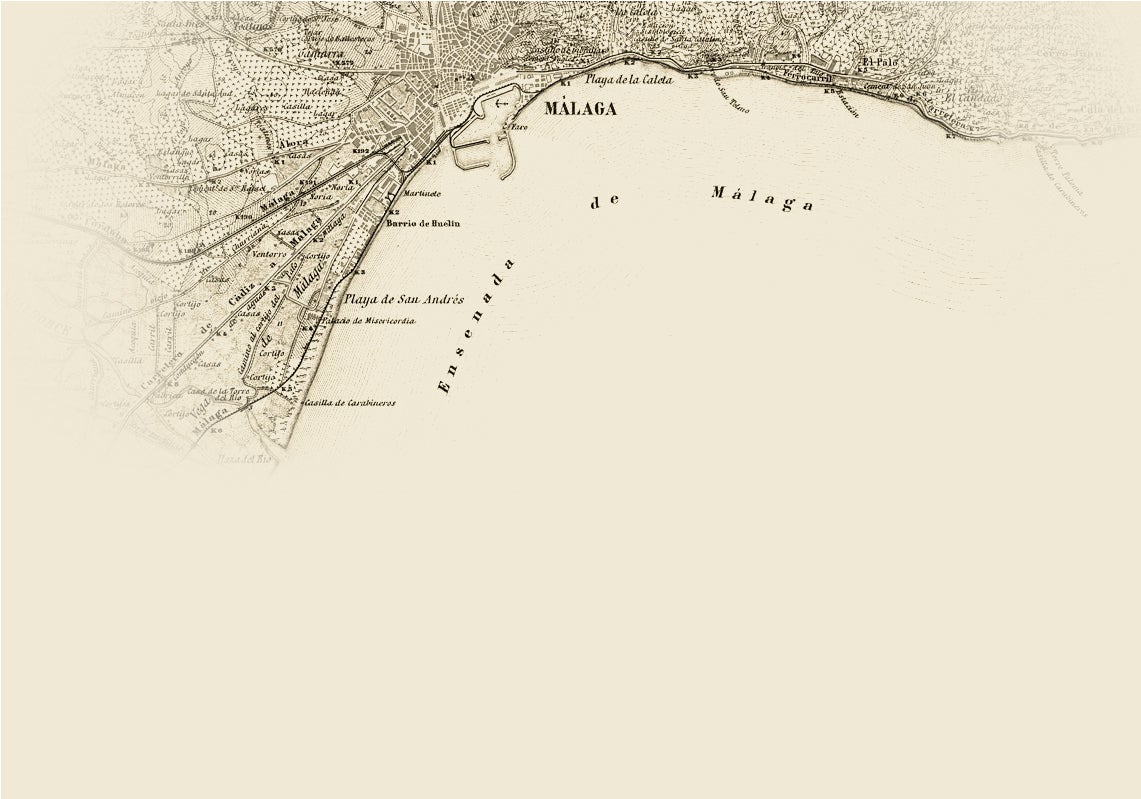

This all started in the 1980s when US researcher Willard C. Frank Jr came across the first Nazi military documents to mention the sinking of a C-class submarine in Malaga in 1936. Javier Noriega, director of Nerea Underwater Archaeology and president of the CMMA (Clúster Marítimo-Marino de Andalucía, a group of private marine-related companies), took up the research baton and investigated the site of the C-3 submarine. He regards its sinking as an "episode of international relevance".

He adds: "This torpedo has huge historical significance from an archaeological point of view, showing that the German navy was getting underwater weapons ready for World War II and that they began trials in Malaga during the [Spanish] civil war."

The expert links this event from December 1936 to the bombing of Guernica four months later by the Condor Legion. These armed forces brought into play new aerial attack techniques, ammunition and all the horrors of war with their sights set on the future global conflict to be played out in Europe.

Operation Ursula

12 December 1936.

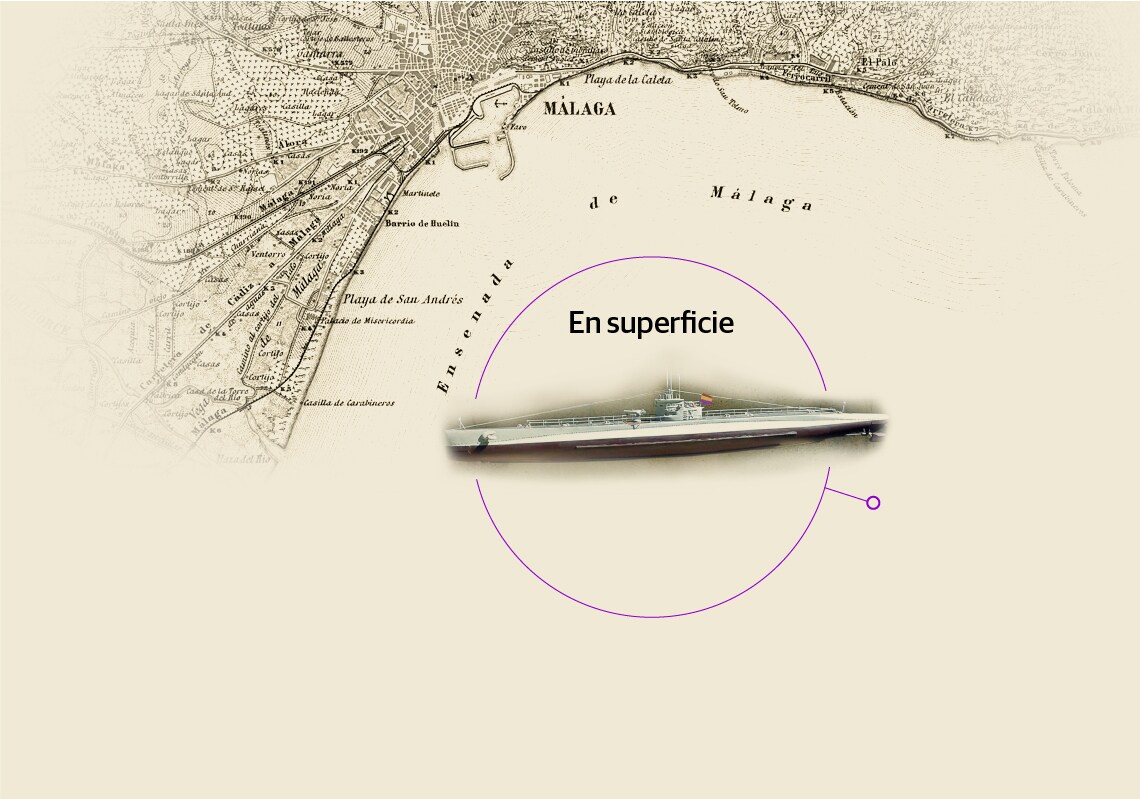

The Spanish C3 submarine was on the surface off the Malaga coastline.

A U-34 Nazi submarine stops 800 metres away, submerged.

It respects the safety distance to shoot one of its torpedoes towards the C3.

The powerful missile hits the hull of the C3 and breaks it in two, sinking the submarine to the seabed.

The torpedo contintues its trajectory until it also hits the seabed 300 metres from the initial impact.

AUX STEP FOR JS

.

The sinking of this sub was clearly not a coincidence, rather the final act of Operation Úrsula, showing Hitler's support for Franco. U-boat 34's first destination was Cartagena, where three G7 torpedoes were fired without hitting any target. According to José Luis Martín, there were two reasons for this failure: it was a new missile that needed calibrating to fire accurately; secondly, a "manufacturing error" with the fuse that was not corrected until World War II had begun. The Italian navy then entered in support of Franco, pushing out the German contingent.

The Guardia Civil and the navy have been analysing how to neutralise the G7 torpedo located in the bay

However, the balance was redressed when the Nazi submarine passed by Malaga, then another Republican navy base in the Mediterranean. The U-boat's commander, Grosse, looked through the periscope and spotted that the C-3, which was patrolling on the surface loading weapons supplies, was within range. The attack by "a foreign submarine", as press reports put it, since the fascist side had no submarines, was fourth time lucky, hitting its mark and sinking the Spanish vessel. It can still be regarded as a failure though as it did not explode, which would have caused the total destruction of the submarine. It just broke it into two, same as it is now, still resting on the seabed

Known about since 2009

It was in 1998 that a diesel oil stain on the sea caused lawyer Antonio Checa to suspect that the remains of a shipwreck could be underneath. That suspicion led to the discovery of the C-3 submarine that continues to fascinate many today. While the site remains "active" and is now publicly known in both scientific and official circles, one nugget of information provided by archaeologist Javier Noriega reveals that the discovery of the G7 torpedo's location actually dates back to 2009. José Ignacio González Aller, a rear admiral in the navy, also a navy historian and director of the Naval Museum who died in 2014, analysed documents on the sinking of the submarine in Malaga and concluded that the torpedo had not exploded.

He passed this hypothesis on to the specialist company, Nerea Underwater Archaeology. The company ran with his hypothesis 14 years ago, embarking on a project approved by, and carried out with support from, the Andalusian Centre for Underwater Archaeology and the Department of Culture for the regional government of Andalucía. Their main goal was to deploy geophysics to locate and research any surviving wreckage in the bay of Malaga, ensuring that it is legally protected against plunder.

The C-3 is of interest for two reasons: it is a general marine archaeology site as well as a war grave

In the case of the C3 sub, "We expanded the search because, where there was a sinkhole and the sea's currents creating movement, some pieces and materials were just lighting up. We observed several anomalies and so we speculated that we could be finding ourselves with the unexploded torpedo, thus confirming González Aller's expert findings," explains the archaeologist, who was joined in this multidisciplinary technical team by Jorge Rey and Adrian Westendorp.

Javier Noriega is thankful for all those who played a part in this discovery: engineer José Luis Martín and filmmaker José Antonio Hergueta for sniffing out the torpedo's location as "it means confirmation of" the theory that it did not explode, as suggested by historian and rear admiral Gonzalez-Aller, an opinion upheld by the then head of the naval base in Malaga, Remigio Verdía, in his incident report in 1936.

"What they have done is really valuable, shedding light on an event that is one of the very few to come to light in Malaga's maritime history, and there's still more to be discovered", states the archaeologist from Nerea. He also expresses his concern for the site being possibly plundered by diving enthusiasts seeking a souvenir.

For this reason he reminds us that the C-3 submarine fulfils two purposes: the first as an "archaeological site that must be investigated", but that it is also a "war grave where we must be sensitive and respectful". He strongly advocates keeping both elements in mind and "always with authorisation from those publicly in charge to handle cultural matters and, following approval of the 2014 maritime law, from the navy as owner of the sunken vessel".

A good example of how differing perspectives can be reunited is the battleship USS Arizona, sunk in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941. The wreck was studied by archaeologists, there is a memorial built over the wreck's site open to visitors and the wreck is designated a national shrine and war grave, still housing its 1,102 deceased crew members.

"With the C-3, the most appropriate thing could be to make a replica of the submarine and a dual-purpose visitor centre in El Palo that would explain both the history of the archaeological discovery as well as providing a space where those deceased sailors could be honoured (37 in all), and where family members would also have a physical space to visit as a memorial to those sailors who died in combat," suggests the head of Nerea. It is a tale still waiting to be told, charged not only with explosives, but brimming with history.

-U81275431256RIU-366x256@Diario%20Sur.jpg)