A protein which can help you age better

Although TP53INP2 cannot be taken orally, there is hope that it can slow the loss of muscle and body strength as we grow old

Jon Garay

Friday, 17 May 2024, 12:45

As we age, our bodies progressively lose power. We observe it in ourselves and more so in our elders. They have less strength, their efforts become increasingly laboured, they get sick more often because their natural defences are not capable of reacting as effectively as they used to and they become more forgetful. The loss of strength is caused by what doctors call sarcopenia, which is the gradual decrease in muscle mass. It is one of the reasons why older people have more falls, injure themselves more easily and need more supervision.

"Sarcopenia begins at the age of 55," explains Antonio Zorzano, head of the complex metabolic diseases laboratory at the institute for research in Biomedicine (IRB) in Barcelona. From that age onwards, muscle mass decreases between 1% and 2% annually and strength declines by 1.5% and 3% from the age of 60, according to the Spanish society of Rheumatology (SER). In men the process is more progressive, while in women it is more sudden due to the menopause.

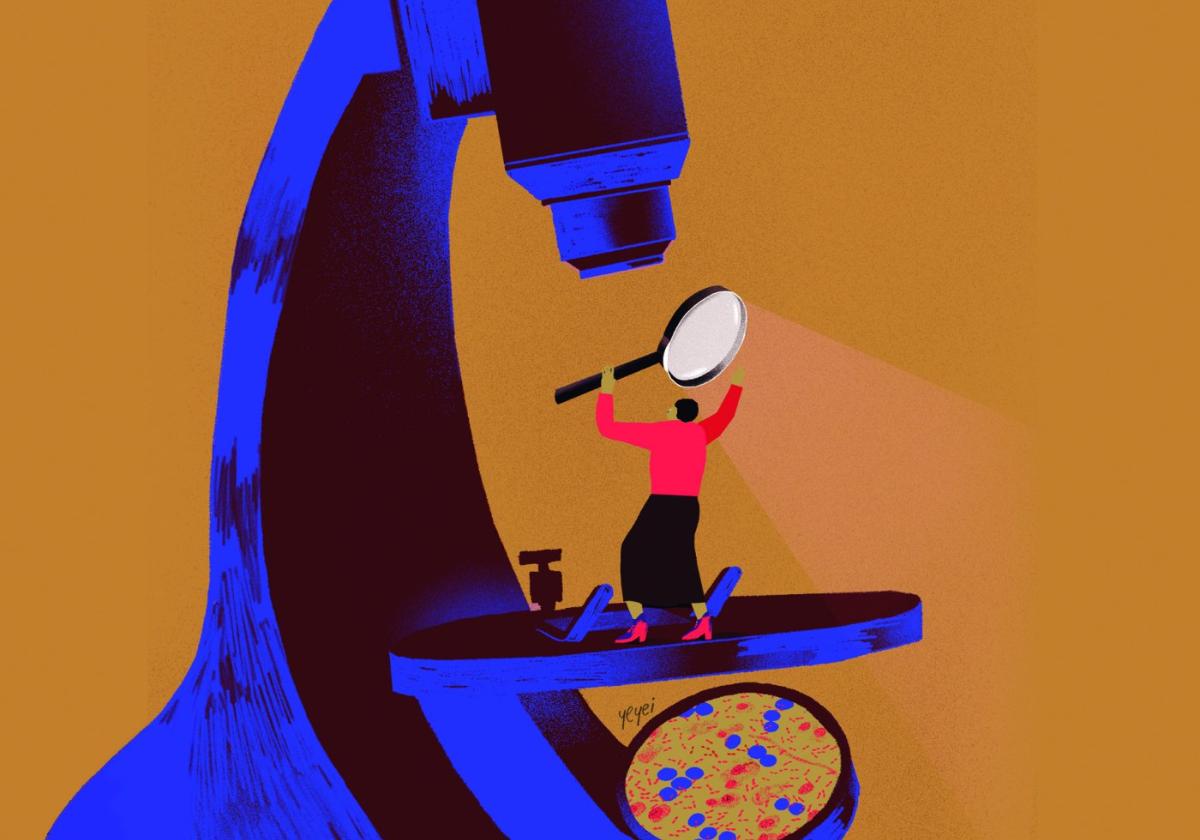

"We know little about how it happens and how to treat it pharmacologically. For example, we do not know how to reverse cancer cachexia, a muscle-wasting syndrome that occurs with some types of cancer," says Zorzano. This medical researcher has co-led a study with Dr David Sebastián from the University of Barcelona in collaboration with Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu (a research facility, part of the San Juan de Dios private hospital group). For this study they have analysed the key role played by a particular protein: TP53INP2. Their conclusion is that high levels of this protein correlate with greater muscle strength and healthier ageing in humans.

Key information

Muscle loss. It begins around the age of 55 and is one of the reasons that explain why older people have more falls.

Different rates. In general, muscle mass decreases by 1 to 2% annually from the fifth decade of life, but it varies among individuals.

Solution. Moderate exercise and a low-calorie diet help delay sarcopenia. Also, a molecule called rapamycin, a medication used, among other things, to prevent rejection in transplants and against some types of cancer

Their research entailed performing a hundred biopsies on muscle tissue samples taken from patients of various ages. When analysing the samples of those aged over 68, they found a lower presence of TP53INP2. They also discovered that elderly patients with a lower presence of this protein had lower grip strength in their hands, one of the best indicators of what a person's quality of life will be like and what diseases they will develop as they age. What's more, a lower quantity of this protein has also been linked to loss of bone mass (osteopenia), the risk of fractures in the event of falls, sleep problems and depression, and even issues with cognitive function. "The most important thing is that those who had more of the protein were ageing better."

What the protein does

What TP53INP2 does is maintain or activate autophagy, the body's natural process by which our cells destroy parts that are defunct or dysfunctional - literally self-cleaning. "It is as if the cell were passing through the garage for a once-over. This protein recognises what is not working well and takes it out of action." This kind of self-cleaning mechanism reduces the likelihood of contracting certain diseases and prolongs life expectancy. Not forgetting, of course, that it helps maintain the muscles. The researchers tested it in two experiments with mice. In one of them they saw that some of the mice "held onto this protein more throughout their lives, which protected them from the sarcopenia that accompanies ageing." It also did similar against age-related metabolic diseases.

Diet and exercise

In the second experiment they investigated whether it was possible to improve the muscle condition of elderly mice. "Using a gene therapy system, we induced the expression of this protein in animals that were already very old. What we saw is that we were able to improve their sarcopenia: their muscle mass and strength increased. Let's say it is a proof of concept that shows that, if you improve this protein and if you improve autophagy, you can improve the level of muscle mass for the animal," says Zorzano. Sebastián adds this point: "This study not only highlights the importance of keeping autophagy active in muscles to prevent muscle loss, but also gives us hope for possible treatments that could improve the condition, or at least mitigate the effects, of ageing on our muscles."

What can we be doing in the interim?

We know that moderate exercise helps because it causes cells to recycle constantly. Also calorie-restricted diets. Lastly, rapamycin, a molecule that activates autophagy (originally developed as an immunosuppressant for organ transplant patients, but now being used as an anti-ageing drug).

So how come TP53INP2 cannot be ingested as other proteins can?

It is not possible as it is an intramuscular protein. Oral ingestion would really degrade its effectiveness. If only we could all just pop a pill and have our muscles improve.