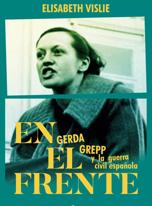

Gerda Grepp, the journalist on the frontline of the Spanish Civil War

A translation of her biography by Elisabeth Vislie puts this long-forgotten war correspondent back into the history books as the last reporter to leave Malaga before it fell to Franco

Francisco Griñán

Friday, 17 May 2024, 20:28

She is often described as a photographer. If she is remembered at all. In reality the long-forgotten Gerda Grepp was also a journalist. So, when she embarked on her mission to tell the world about the civil war happening in Spain, she wangled a camera for herself so her reports could be imprinted in the memory of her readers. This Norwegian correspondent was the last journalist to leave Malaga before its fall in February 1937 and one of the few to tell us how it was on the front. Her fondness for wearing trousers, which left many soldiers open-mouthed, was a symbol of her expression of freedom - this indomitable and, paradoxically, near-invisible woman. Her biography, written by countrywoman Elisabeth Vislie in Norwegian - Ved fronten (On the Frontline) - has now been published in Spanish by Malaga's Plankton Press and will be presented in Libería Rayuela on 21 May.

"A woman in long trousers! Something so strange that the militias in the mountains of Malaga had never seen such a thing before," Grepp wrote in 1937 in one of her letters sent home, family correspondence that was uncovered by Vislie's book. "It was not so strange at the time and less of a rarity if you were at the front, but many of those militiamen from the Alfarnate front, country folk, had never seen a woman wearing trousers," says Grepp expert, Enrique Benítez. It was Benítez who wrote the preface to the Spanish edition - En el Frente. Gerda Grepp y la Guerra Civil Española, (On the Frontline. Gerda Grepp and the Spanish Civil War).

Zoom

BIOGRAPHY

-

Title En el frente. Gerda Grepp y la Guerra Civil Española

-

Author Elisabeth Vislie.

-

Publisher Plankton Press 288 pages

-

Price 19.90 euros.

-

Malaga launch with author (in Spanish): Libería Rayuela, Calle Carcer 1, 21 May, 6.30pm

Benítez claims this woman was "part of the history of Spain." Not only was this journalist the last to leave Malaga, but also last to leave Bilbao when the Republicans lost that city too. She also covered reporting on the Madrid front. Yet she fell into complete oblivion, even in her own country, despite the fact that the journalist, spy and writer Arthur Koestler wrote of her work in his memoirs. Some written accounts that Elizabeth Vislie found when investigating Grepp's life and work convinced her that Grepp, the war correspondent, should be regarded as a fundamental character of the 20th century: "The story of Gerda Grepp is the history of the press, the history of Spain and the history of women."

Ideologically committed to social democracy, Grepp lived in a time when journalism was seen as another player wrapped up in the conflict. For this reason, the journalist "travelled to where the lines were being drawn in the sand, to the trenches of the war in Spain, to report, no matter what the cost," says her biographer about Gerda's idealism, who put her fight for democracy and against another world war far ahead of her own fragile health and private life. "Although she had TB and only one lung, and despite leaving two children at home in Norway, she did not allow herself to be intimidated," says Vislie, whose book focuses on Grepp's trip with Koestler to Malaga and their forays to the main fronts in the province: Alfarnate and Marbella. Grepp, always in trousers, camera in hand. This is how she was portrayed by Malaga film director José Antonio Hergueta in the recent Goya-nominated documentary: Caleta Palace.

The children of Malaga

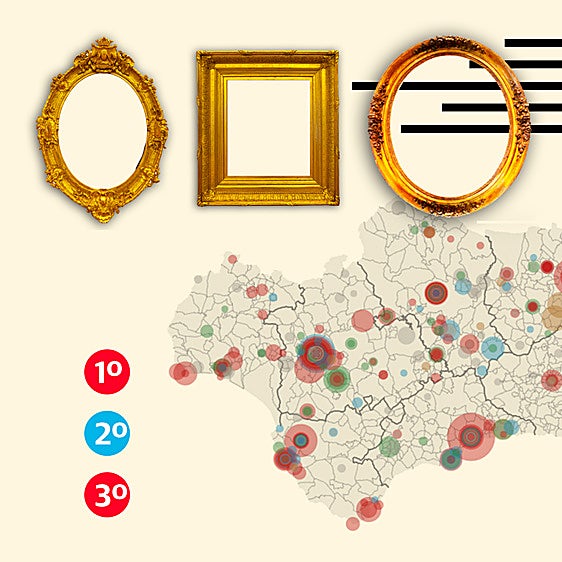

Upon arriving in Malaga, Grepp was already aware that the republican forces had stopped supplying weapons and that there was a lack of control along the frontline. She then turned up to an event being covered by the writer André Malraux: the last raid of the battered and weakened republican fighter squadron as it tried to protect the retreat from Malaga along the road to Almeria. As Benítez explains: "She wanted to be where the action was but she also realised that the bombings of the rear guard and the suffering of the general population were not being covered so, when she reached Malaga, she took photos of the children and spoke to people whose lives were now at risk." These were the people that she took great care to portray in her series of reports on the war front: 10 Days in a Dying Malaga'.

However, the republic did not make it easy for Gerda, only allowing her to publish her account as though from still in the city because their censorship was embargoing all information about the fall of Malaga. Despite that difficulty and the imbalance in the fighting there, Grepp avoided pointing a critical finger at the republican government's abandonment of the city and turned her attention to the population - the soldiers, the women, those there to help, and the children. Her intention was not to get bogged down in debates on the risks of different democracies and promoting anti-fascist propaganda. Despite being the last reporter to leave Malaga, she confessed in a letter that "one feels a real coward leaving behind a city in which so many are going to die".

While in the trenches at Malaga, this journalist saw the writing on the wall for the tragedy that was to unfold during the exodus to Almería. After her departure in February 1937, Grepp continued reporting until the end of the Spanish conflict, although her fragile health began to suffer and she ended up dying of TB in 1940 in German-occupied Norway, at the dawn of a world war that she could not prevent.

"If she had not committed herself to her work, she probably would not have died so soon," muses Benítez about this sensitive, trouser-clad woman, a feminist and pioneer who, paradoxically, fell into oblivion with her premature death. Nevertheless, like so many unnoticed people, it is her work that has ended up pulling her out of invisibility, reserving a well-deserved place for her in history.

-kHDG--1200x840@Diario%20Sur.jpg)